The $17.2 billion in the joint endowment between Texas A&M and the University of Texas passes through a spiderweb of state officials, university board members and financial managers before being invested in companies. What it doesn’t pass through is a committee on investor responsibility.

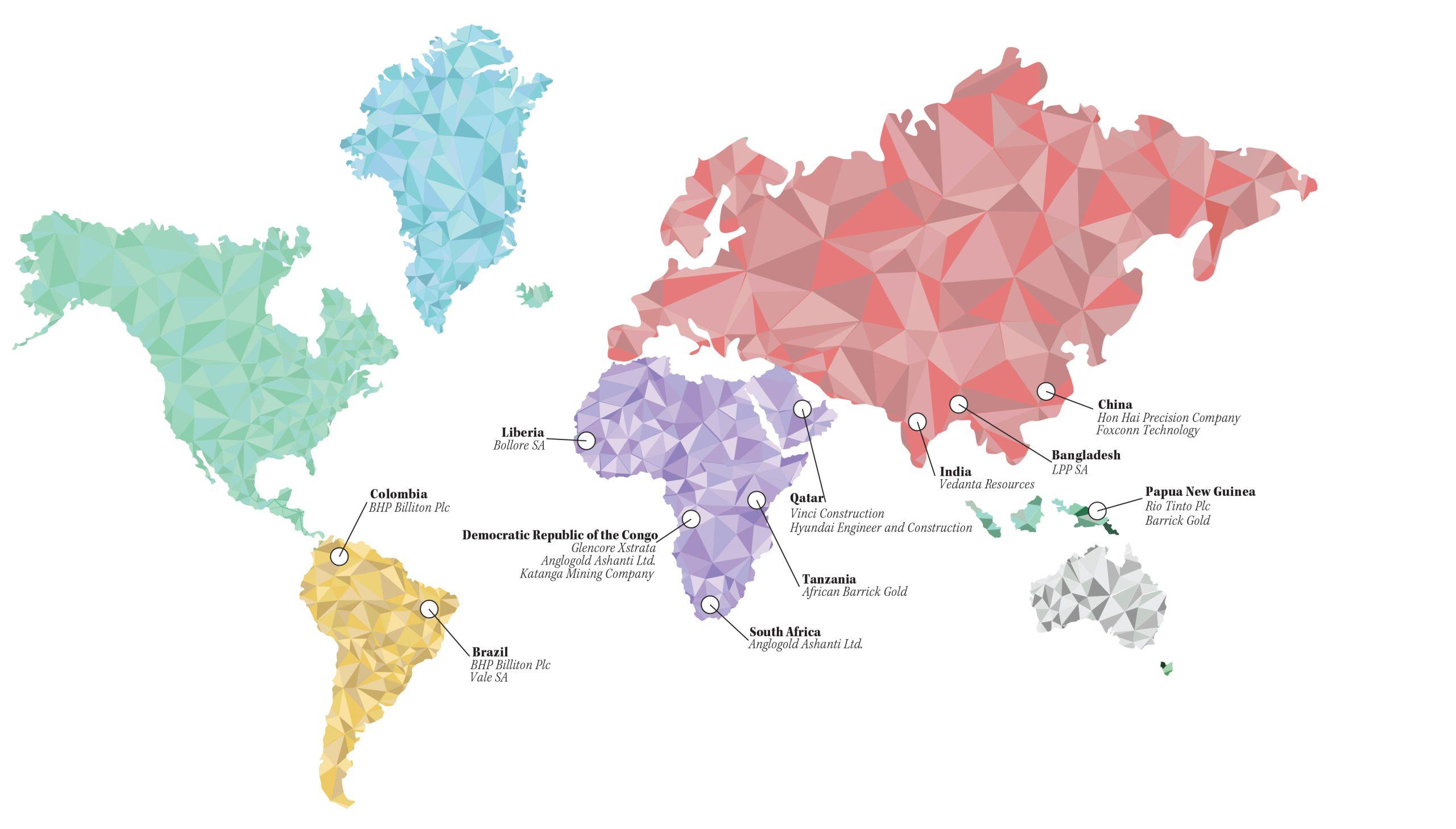

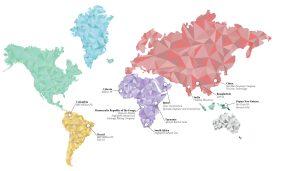

As a result, a three-month investigation by The Battalion shows the Texas A&M and UT systems are invested in at least 50 companies with allegations ranging from aiding genocide in Sudan to broader human rights violations across the globe.

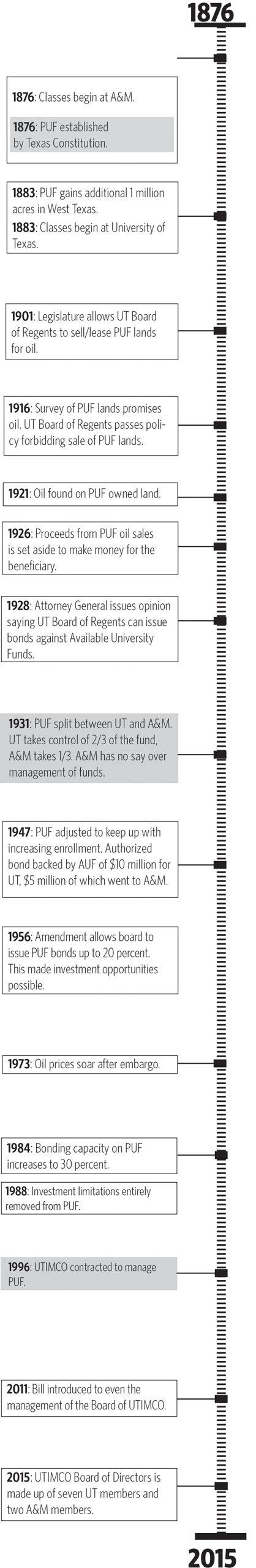

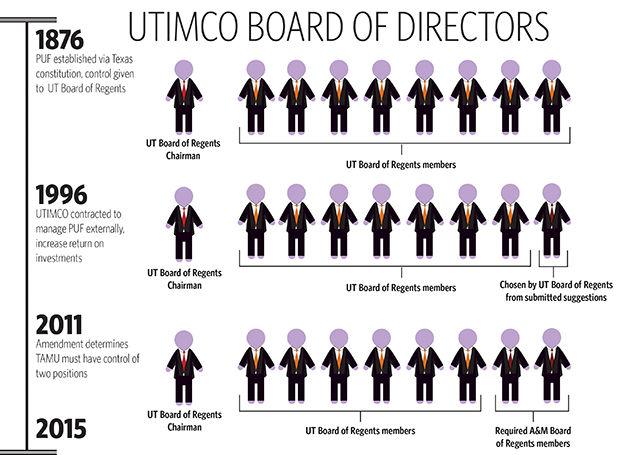

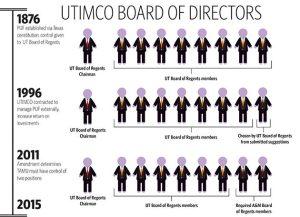

The Permanent University Fund has been managed by the University of Texas Investment Management Company, UTIMCO, since 1996. Two-thirds of the payouts from the fund go to the UT System, and the remaining third goes to the Texas A&M System. These payouts fund scholarships, faculty salaries and student development programs at the 17 institutions in the two systems.

The 50 companies identified by this investigation have received approximately $78 million from investments made by UTIMCO. The allegations against those companies are lengthy and include violations of human rights in Qatar and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, sidestepping sanctions against the Islamic Republic of Iran and accusations of bribery on an international scale.

UTIMCO’s lack of an ethical policy

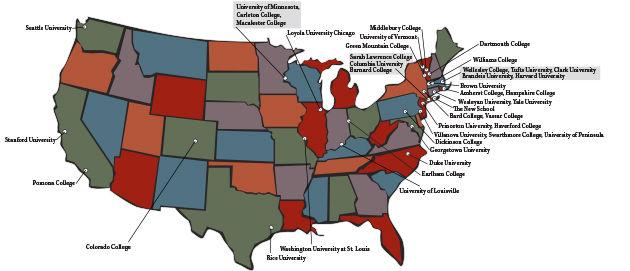

The endowment is in range of the top-10 largest university endowments in the United States. Among that group, it is the only endowment that has not established a social policy or the equivalent of a Committee for Investor Responsibility. At other university systems these committees function to eliminate unethical companies from their massive investment portfolios that otherwise would fall through the cracks.

UTIMCO does have an ethics committee, but it only operates to keep from investing in companies they personally have an interest in, and does not function to review companies with social abuses.

Financial experts suggest there are both reputational and financial risks to the university for being invested in unethical companies.

Lori Taylor, director of the Mosbacher Institute at the Bush School of Government and expert in school finance issues, spoke generally about the potential character risk to the university if it is found to be invested in unethical companies.

“I think there is a reputational risk to the university to be associated with what you call the bad actors,” Taylor said. “There is an inconsistency with messaging between the university’s position with a lot of these issues and … that inconsistency represents at the very least a political risk for the university.”

Julian Gaspar, director of the Center for International Business Studies at Mays Business School and former economist at the World Bank, said this reputational risk is the consequence of the university not meeting a greater moral responsibility that is inherent in institutions of higher education.

“As a university in particular, where we are educating people, we are not just profit-maximizing institutions,” Gaspar said. “We are in the business of education and trying to mold the minds of young people, and I think we have a greater responsibility in that respect. The world is changing, and we need to make the world a better place. We just cannot afford to look at return on investment.”

UTIMCO CEO Bruce Zimmerman counters that the economic performance of the portfolio is the only thing that matters.

“We are not a political organization. We are not a partisan organization. We are an investment management organization,” Zimmerman said. “And we make investments based on economic decisions.”

An attempt by Texas lawmakers in 2009 to force UTIMCO to divest from companies operating in Sudan passed an early vote in the House of Representatives with 114 votes in favor and 23 votes opposing the measure. It later died in the Senate Finance committee.

The House Research Organization, a nonpartisan department in the House of Representatives, noted in the bill analysis the financial risks the companies posed to the endowment, as well as the efficacy the divestment movement was demonstrating at the time on the genocide in Sudan.

“In addition to obvious moral reasons, there are financial reasons for this divestment,” stated the bill analysis for that hearing. “According to a 2008 Sudan peer performance analysis, the ‘worst offenders’ in Sudan underperformed their peer group average by over 22 percent over a three-year period and over 45 percent over one year. This period corresponds with the rise of the Sudan divestment movement and shows that it indeed works.”

Zimmerman said UTIMCO focuses on economic performance only. His statements are consistent with ones he has made in the past, when he said any social policy would be a slippery slope that would ultimately leave the universities making less money.

“The context of all this is if you make economic decisions based on noneconomic reasons, there’s an economic cost,” Zimmerman said at a UT Board of Regents meeting in September 2014. “Once you decide there is one political or social issue that merits an investment decision, where does the list end?”

Divestment versus proxy voting

The notion a social policy for the endowment would lead to a slippery slope of divestment does not have a precedent in at least 42 of the universities that have established the equivalent of a Committee on Investor Responsibility. Harvard University, which established the first ethics committee in 1972, has only ever divested from companies related to tobacco, apartheid South Africa and genocide in Sudan.

Cristian Tiu worked at UTIMCO from 2003 to 2006 and now sits on the Committee of Investor Responsibility at the University of Buffalo. He said determining when companies are violating laws and ethics is more difficult than it seems.

“Learning about these things is slightly complicated, because you have to go and download the reports of different entities that you are interested in and then you have to sort of infer from there what it is that you’re holding that other people may find undesirable,” Tiu said. “This is a learning process.”

Tiu said one of the defining questions remaining in endowment management is what to do once you have identified any bad actors.

“There are difficult things actually,” Tiu said. “Even if you reach out to people who advocate social responsibility, and then you ask them, ‘What exactly is it that you recommend we do?’ You don’t always get a clear answer.”

Gordon Clark, director of the Smith School of Enterprise and Environment at the University of Oxford, sees both advantages and problems with a divestment-only response.

“When you indicate publicly that you’re divesting, you’re signaling that in some sense the company fails a test of legitimacy,” Clark said of the positive effects of divestment.

However, Clark said often times divestment does not change the company’s behavior — in many cases it only makes it cheaper for other investors to buy stock in the bad actors. Instead, he advocates for institutional investors to hold their shares of the company and use their voting rights to help shape their social policies.

“I think in principle you stay and engage — I think divesting makes no appreciable difference to the cost of capital and can be an empty gesture,” Clark said.

Proxy voting however has its limits in the pressure it can place on a company, because it often requires the institution to hold a significant part of the company. This problem is especially pronounced for UTIMCO, which is limited by the Texas Constitution in how much of a single corporation it can own.

The bottom line first

November 12, 2015

0

Donate to The Battalion

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas A&M University - College Station. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

More to Discover