One should begin, I suppose, by giving the devil his due: no matter how much it comforts climate change activists to think otherwise, a major reason climate change skeptics persist has little to do with their supposed ignorance and everything to do with our occasional sloppiness. Sometimes it is us flubbing up on the difference between weather and climate (a level of carelessness that advocates simply cannot tolerate); other times it is a gratuitous focus on headline-grabbing factoids: “The Warming Climate Is Making Baby Sea Turtles Almost All Girls” may very well boost newspaper sales — and it may very well be true — but it isn’t the entire story on climate change.

It’s a bit like the old Cyanide and Happiness comic. The first character tells a random factoid to the second — the type of thing people whip out at parties to make themselves sound more interesting than they actually are. Hands on his hips, head held high, he declares: “Yeah, I love science!” The second character, exasperated, then lectures him about how a true lover of science is fascinated with “the tedious little bits as well as the big flashy facts.” He concludes, with a bluntness that should make all Aggies withering away under Bachelor of Science degrees proud: “You don’t love science, you’re looking at its butt when it walks by!”

The truth about climate change is that, while absolutely real, when you zero in on “the tedious little bits,” you begin to understand its complexity. That was the major takeaway when I spoke with Perry Barboza of Texas A&M’s Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences Department earlier this week: While it is true that average global temperatures have risen by 1.5 degrees Fahrenheit over their 1951 to 1980 mean, describing all 196.9 million square-miles of the Earth’s surface with a single statistic can be misleading.

Brace yourself, Ags. This is where things get complicated.

First things first: climate change affects different geographies in different ways, and not all changes are bad in the short term. As Barboza said, “We’re actually going to see a short term [productivity] increase over a decade or two on the Great Plains. It’s going to get greener so it’ll be more productive. But as that continues, it’ll start to become drier… and that’s basically going to cause drought.”

Second things second: rising temperatures are not all that’s important; the climate is always changing and animals are always adapting. What’s just as important is the pace and volatility of those changes — something which the average global temperature statistic simply does not capture — because if animals don’t have time to adjust, they die.

Got it? Awesome. Now consider the example of the American Black Duck, a migratory fowl that breeds along the eastern seaboard from the northern regions of Canada all the way down to Florida. “They have to attenuate risks at both sides of the continent,” Barboza said. Climate change increases the environmental risks to which the American Black Duck is exposed: rising sea levels flood crucial portions of their habitat and introduce known predators such as foxes. When there is uncertainty about things such as food, the ducks adjust by living longer and not breeding in the short term. If they go too long without a stable food source, they simply die off. That’s one of the reasons their continental population numbers have dwindled from 1.5 million in the 1950s to about 600,000 today.

The first people to see this are usually not scientists, but hunters; they notice that duck populations aren’t nearly as high as they once were and the population isn’t rebounding as quickly as it once did. In fact, the vast majority of public conservation funds come from hunters — not a liberal group by any stretch of the imagination — through the sale of hunting licenses. Of the 21 states which have added the right to hunt and fish to their constitutions, 19 are deep red. (The noteworthy outlier is Vermont, from which a certain Democratic Socialist hails.)

Here’s the kicker: much like the number of American Black Ducks, the number of hunters has been decreasing as well — by about 50 percent over the past 50-years. So while the American Black Ducks’ population has been dwindling in part due to climate change, they are also dwindling because public conservation funding is flagging due to decreasing revenues from the people who hunt American Black Ducks.

If you thought reversing climate change was difficult, try squaring that circle.

How we oversimplify climate change

October 23, 2019

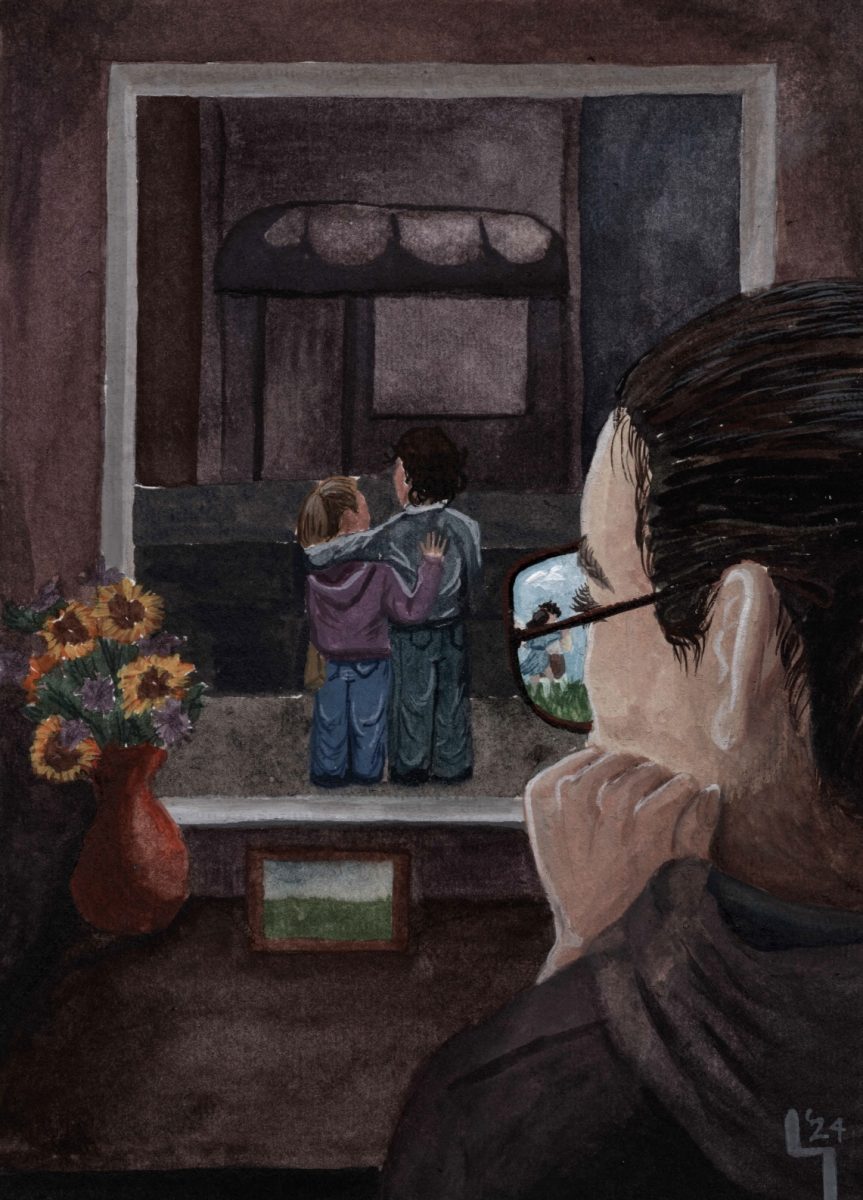

Photo by Creative Commons

Amid new environmental risks, the American Black Duck population has dropped from 1.5 million in the 1950s to about 600,000 today.

0

Donate to The Battalion

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas A&M University - College Station. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.