The year is 2028 and most university students can expect to confidently strut across a glimmering stage knowing they’ve graduated with a 4.0 GPA. We can only dream, right? Universities like Harvard don’t have to.

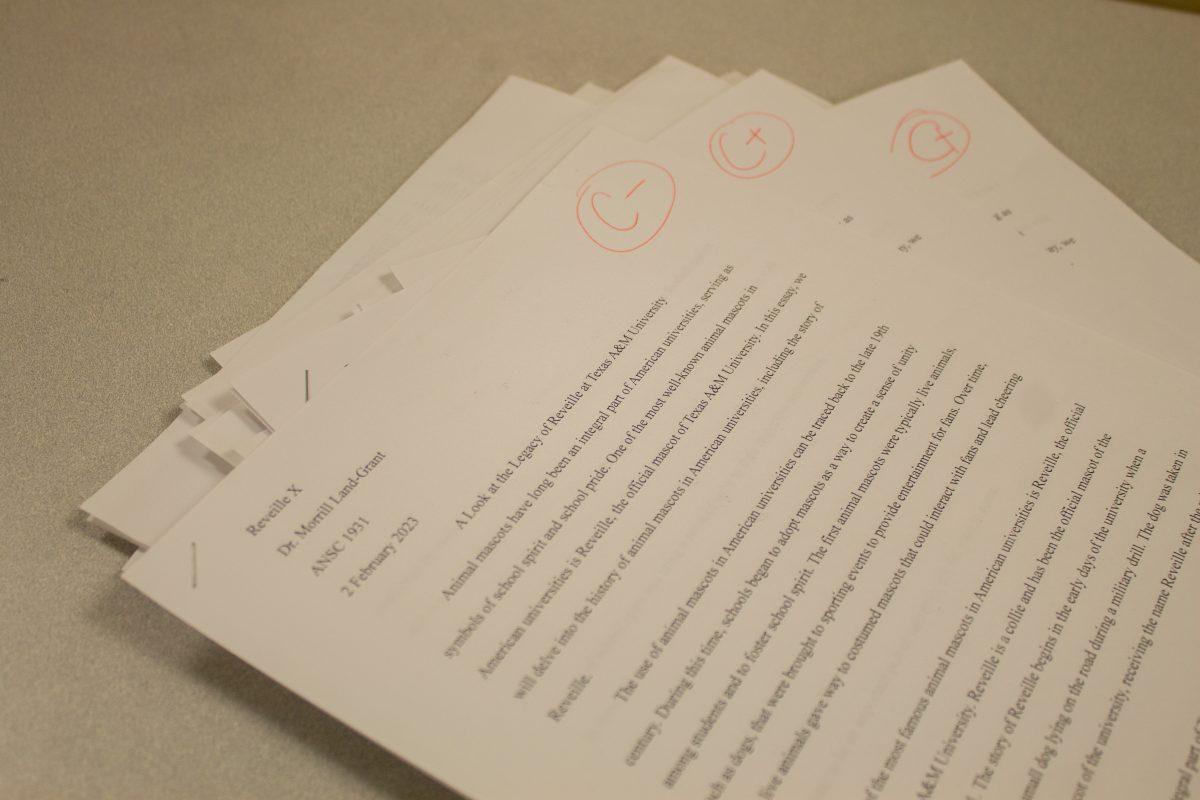

Grade inflation, a trend of increasing GPAs over time, has been on my mind since I glimpsed a telling graph published by The Harvard Crimson. According to the graph, Harvard’s average GPA has increased by 10% over the past 17 years — meaning it’s estimated to reach 4.0 by 2028.

While Texas A&M students won’t be at a 4.0 by then, there is a steady increase that could make 4.0s average and it doesn’t mean this generation is becoming full-fledged geniuses.

Research conducted by former Duke professor Stuart Rojstaczer and former Furman University professor Christoper Heeley confirmed A’s have become the most common letter grade in four-year universities since the 1990s.

While some may rejoice over the abundant showers of good grades, I worry about the long term consequences.

Could this grade inflation be indicative of an increase in the quality of education or the ability of today’s college students? Maybe, but there are many other factors at play.

Rojstaczer and Heeley suggest a “consumer era” as the initial cause of the inflation trend, where students began shopping for universities as they increased tuition rates and competed for distinguished titles.

Universities began seeing giving out excellent grades as a means to ensure a high success rate in student employment after college.

The goal: propping up university rankings and prestige by inflating grades.

Today, professors are incentivized to give out A’s because of rating sites like RateMyProfessor and even A&M’s course evaluations. They may inflate grade scales to please students instead of maintaining grading standards that reflect academic achievement.

The commonality of A’s could be proof the college system is content with ignoring the implications grades have on standards set for the future workforce, and employers are taking note.

A survey from the National Association of Colleges and Employers shows a drop in job screening for GPA to a low 37% in 2022-23.

Before, employers hired college graduates with high GPAs because they likened their grades with acquired skills; this, however, is becoming less of the case. Now, because applicants get lost in a sea of degrees and A’s, employers have been testing out skills-based hiring; putting more emphasis on soft skills like time management.

Perhaps my warnings of GPA inflation sound like a superstitious foretelling of doomsday. However, the threat isn’t looming overhead — it’s now. The sky is falling and your choice is either to look up or say it hasn’t fallen enough for you to notice.

While you may not yet feel the effect, A&M data suggests grade inflation is persistent throughout all majors including STEM. The differences lie in rate of change, but all point to a consistent increase.

The average grade at A&M was a B for decades, now it’s increased to steady A’s since about 2008. A lack of cultural acceptance for grades like B’s cause students to perpetuate the inflation cycle by enrolling in courses where A’s are average because they see a balanced spread of grades as a sign of poor instruction.

The advancement of grade inflation could eventually sabotage students from success in the job market to our generation’s academic fulfillment.

It shouldn’t be this way. What about students who want their A’s to mean something?

At the start of the semester, I registered for a class that was structured as an open conversation, with little input from the professor. The class discussion was forced and generic. When I looked up past data, the average grade for the class was an easy A.

Because even a chat with friends would’ve been more productive, I decided to drop the course before the add/drop period expired.

I would’ve learned nothing and the notion of receiving a participation grade would’ve left a searing hole in my brain.

The business of universities should be to consider the student’s relationship to grades as one that can foster intense, deeper study and academic fulfillment. Not “the business” of out-ranking other institutions when it comes to GPAs.

Grade inflation is harming all majors, with humanities as the first within reach. For the sake of academic accountability, university committees should care.

If mediocrity means an A, then I don’t want it.

Valerie Muñoz is a journalism junior and opinion writer for The Battalion.

Analysis: When ‘A’ means average

February 9, 2023

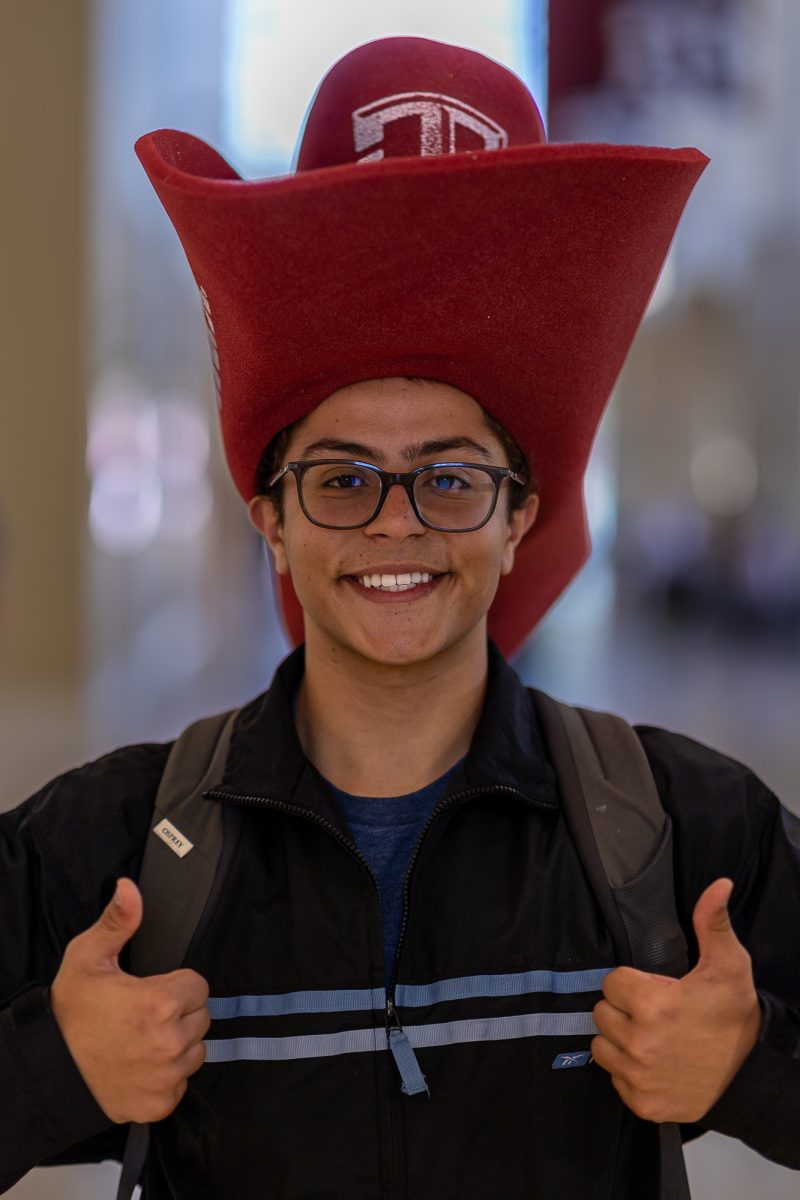

Photo by Photo by Pilar Ibarra

Do grades reflect academic achievement anymore? Opinion writer @Val4Batt explores grade inflation in addition to its effect on the college experience and career prospects.

0

Donate to The Battalion

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas A&M University - College Station. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

More to Discover