I spent Election Day 2020 as a poll worker near A&M Consolidated High School, right off Harvey Mitchell Parkway. It’s a decent gig if you can get it. At $12 an hour, the pay is respectable, and if your political party knows what it’s doing, they provide lunch for free. Indeed, the only real drawback is having to arrive at six in the morning for a 14 hour day.

Still, that’s a small price to pay to participate in what I affectionately call the grunt work of democracy.

The day begins by moving campaign signs the appropriate distance away from your polling location (trust me, it’s more of a hassle than you’d think). Afterward, your time is consumed with keeping the line moving, making sure no one enters with political messaging and ensuring everyone the state allows to vote gets the opportunity.

In other words, what’s so gratifying about the job isn’t the pay (though it’s decent) or the free sandwich (though it’s delicious). Rather, it is the privilege of taking up your small part in history.

And I don’t mean that politically.

Keen readers will remember that it was this columnist who wrote the Joe Biden endorsement a week ago. They may deduce from the piece, however unfairly, that he is something of a political partisan. But if you are anything like me, from the moment you raise your right hand and take your oath, you find your political persuasion melts away. It’s instantaneous. You can’t control it. And why would you want to? From doors-open until doors-closed, you become uninterested in the outcome of the election and fixated on the particulars of your polling location.

By midday, you will have figured out the directions which keep things moving. They’re short and punchy, yet polite.

“Please have your IDs out and your phones away!”

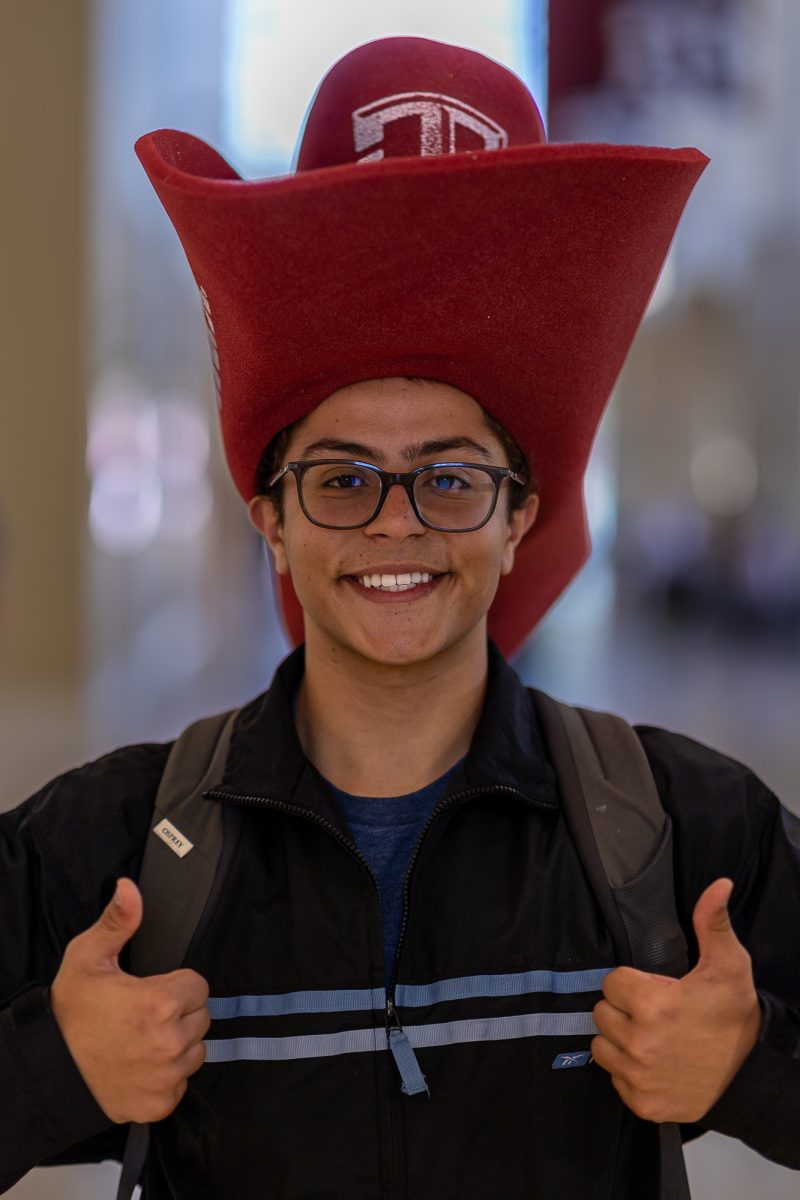

“Sir, can you remove your hat for me, please? It has political messaging on it. ”

“You’re good to go, ma’am! Please visit the gentleman to your left for next steps!”

Trust me, if the political division in America has exhausted you, become a poll worker. It’s all the reprieve of checking out for the day without any of the guilt. In Brazos County at least, the local branches of the Democratic and Republican parties staff polling locations. But in my time there, the election results never came up. Indeed, there was the weighty sense that to broach the topic would be impolitic, that the outcome wasn’t the reason we were all there. Instead, I spent the day watching Republican poll workers assist Democratic voters and vice versa. I watched teenagers bound from their election booths, ecstatic at having exercised their civic duty for the first time.

The job will give you a little more trust in the system. It will inspire a bit of faith in humanity.

And I suppose it was because of this professionalism, this cordiality, this geniality, that I found myself wrong-footed when I finally checked the election returns after closing up shop for the night.

Florida, the state which commentators had predicted Biden would win by a two and a half margin, was breaking sharply for the president. The polls were wrong again. It was 2016 redux. It was like failing an open book test.

And as quickly as the aforementioned puddle of political feelings had formed, those same feelings re-coagulated.

At that moment, I didn’t think about the president’s tax policy or his foreign policy. I didn’t dwell on how he and Mitch McConnell have stuffed the courts with judges. No, at that instant, I thought only about those things which went past mere disagreement, those things which, to my mind, were beyond the political pale.

I thought about the Muslim Ban. I thought about the child separation policy. I thought about Charlottesville, where white nationalists, many of whom have been inspired by the president, invaded the city like rats coming from the sewers.

These last four years, and those events in particular, had the unmistakable stink of a country turning slowly toward fascism, and I wasn’t prepared to push America’s luck for another four.

But then something miraculous happened: In what history will surely dub “The Revenge of John McCain,” Fox News and the Associated Press called Arizona for Biden. Wisconsin and Michigan came the morning next. And after several days of interminable waiting (during which I learned the basic algebra required to calculate the percentage of remaining votes a candidate needed to win), Biden’s home state came through. It had a touch of political poetry even this cynic could enjoy.

The reaction was instant. Celebratory crowds poured into the streets. They were people whom history tells us should not get along. They were black and white, straight and queer, religious and atheist, liberal and conservative. They were from such diverse places as Georgia, Pennsylvania, New York, Texas, California and Washington, D.C.

These people had come together during a century-defining pandemic to pull off the largest exercise in democracy America had ever seen. At a time when they could be forgiven for having their worst moment, they had their best.

And upon seeing those parades, that dancing, the champagne jubilantly sprayed into those happy faces, my mind finally turned to Albert Camus’ 1947 novel, “The Plague.”

The book describes the work of Bernard Rieux, a physician whose small, provincial town is overtaken by an outbreak of the plague bacillus. Officials put the city on lockdown; the plague decimates the population; there is government ineptitude at every turn. But more than a tale of disease, the late professor Tony Judt has argued the plague bacillus represents the danger of “dogma, conformity, compliance and cowardice in all their intersecting public forms.”

In that sense, the book’s plot should sound familiar.

But one day, the plague simply lifts. For reasons not altogether clear, it has taken the lives of some and spared the lives of others. The remaining townsfolk spill into the streets, their joy borne as much from happiness as relief.

All things told, it is a happy ending. And so is ours.

Yet how Camus chose to end “The Plague” has always stuck with me.

Maybe it will stick with you as well. Let it be a reminder of what this country — not just the president — has wrought these past four years. Let it be a reminder of grim possibility.

“And, indeed, as he listened to the cries of joy rising from the town, Rieux remembered that such joy is always imperiled. He knew what those jubilant crowds did not know but could have learned from books: that the plague bacillus never dies or disappears for good; that it can lie dormant for years and years in furniture and linen-chests; that it bides its time in bedrooms, cellars, trunks, and bookshelves; and that perhaps the day would come when, for the bane and the enlightening of men, it would rouse up its rats again and send them forth to die in a happy city.”

Joshua Howell is a computer science PhD. student and the assistant opinion editor of The Battalion.

Election week meditations

November 10, 2020

Photo by Photo by Meredith Seaver

Vote Here Sign

0

Donate to The Battalion

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas A&M University - College Station. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

More to Discover