“If God will not let homosexuals into his kingdom, I do not see how we can recognize them as an active part of Texas A&M.” — Letter to Editor, The Battalion.

Campus reaction to GSS was, at best, polite yet unsympathetic. At worst, it was objectively hostile. In his thesis, “Lesbian and Gay Student Mobilization at Texas A&M University,” Andrew D. Vaserfirer found that many Aggies at the time “suggested violence as the best way to deal with the GSS.” Some students went so far as to say they would “beat the hell out[t]a the GSSO and all of its kooky-queers.”

A pivotal moment happened in November 1976 when no less than the Corps Commander proposed a bill in the student senate urging the university not to recognize GSS. The resolution passed by a 45-15 margin despite Michael Garrett speaking to the senate for over 30 minutes. The next day several senators were quoted in The Battalion as saying that, win or lose, they “want[ed] to see A&M go down fighting.”

(I’ve got a story for you, Ags…

That the Corps was the direct cause of so much hostility toward GSS cannot simply be blamed on their dominance on campus. In fact, scholarship on traditional military institutions has shown they can be breeding grounds for sexism and homophobia.

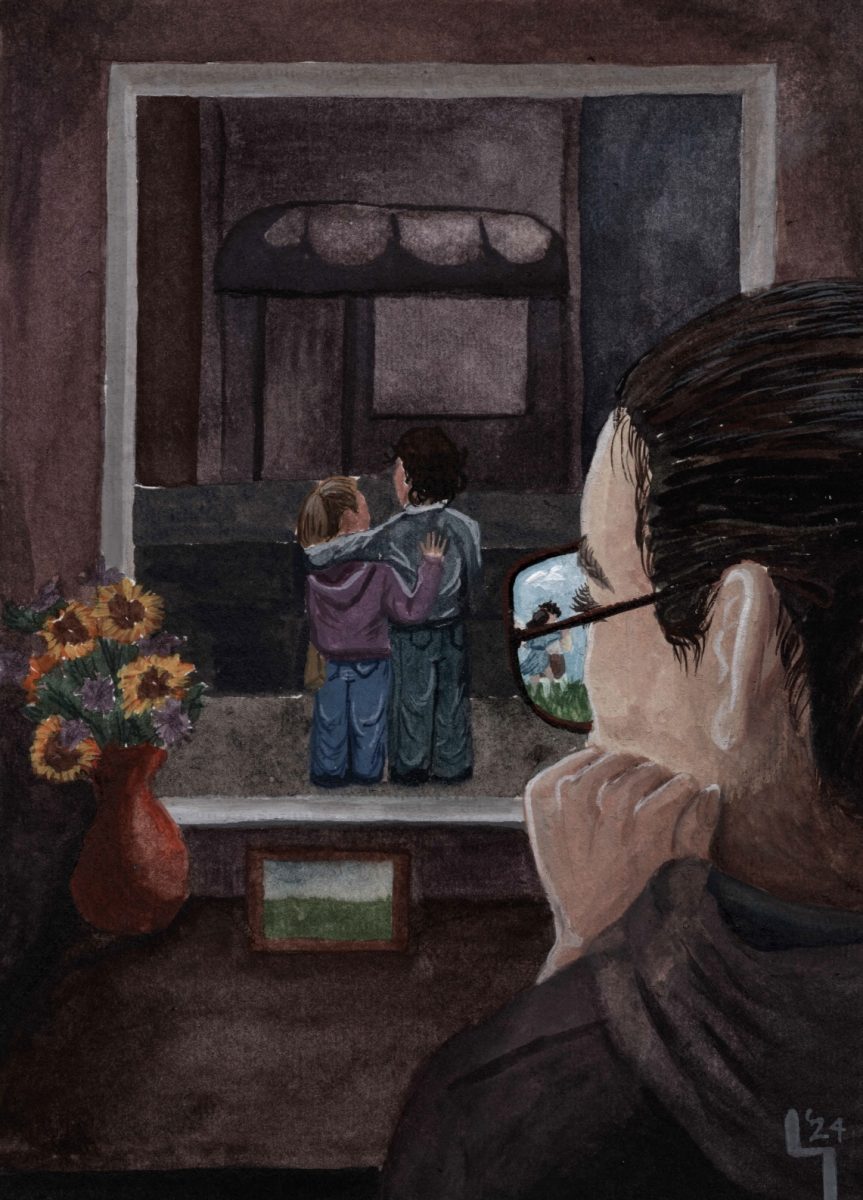

Nevertheless, the antipathy toward GSS was not uniform. Garrett said that, once, a high ranking member of the corps attended one of their parties. Sara Herlick, who was a teaching assistant and increasingly out on campus, still recalls a member of the corps giving her a big hug after he passed one of her classes. And by the mid-1980s, it was not uncommon for some of the more visible GSS members to be quietly pulled aside by a member of the corps and told to keep up the good work.)

To be sure, it was an unambiguous defeat for GSS, but it wasn’t an unmitigated disaster. The mere fact they were getting attention was productive. Indeed, until then, GSS had kept a low profile, not dissimilar to how Garrett had comported himself when first arriving at A&M. (Vaserfirer’s thesis notes that this is common for minorities in environments which are hostile to their existence. But for what it’s worth, Herlick says there was a running joke among the group, that “the boys were in the garage smoking dope and shaking like crazy, shaking like a leaf!”) Therefore, the significance of Garrett, who had only recently come out in The Battalion, standing tall for his organization simply cannot be ignored. If GSS were to be smothered, it would be with the soil in which they would grow.

For the next several years, both the court case and campus activism moved glacially, with little, if anything mentioned in the press aside from the occasional update about how the court case was progressing.

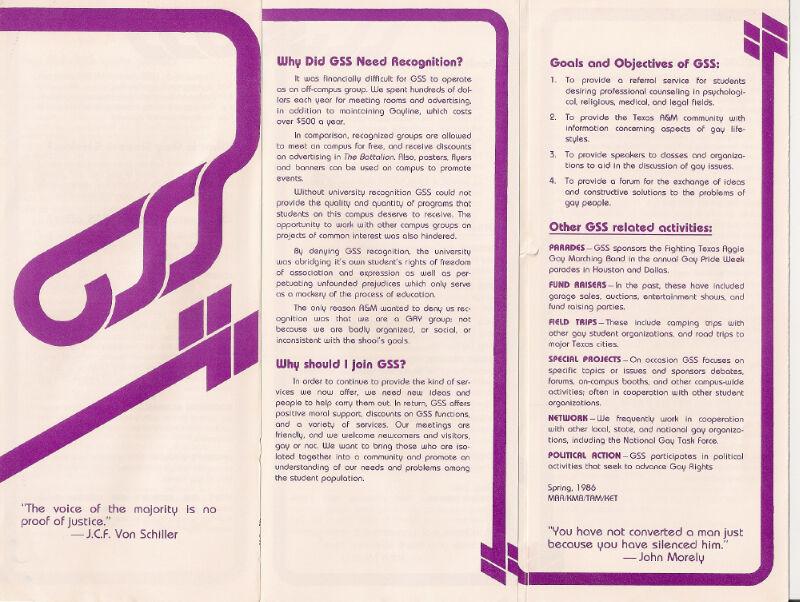

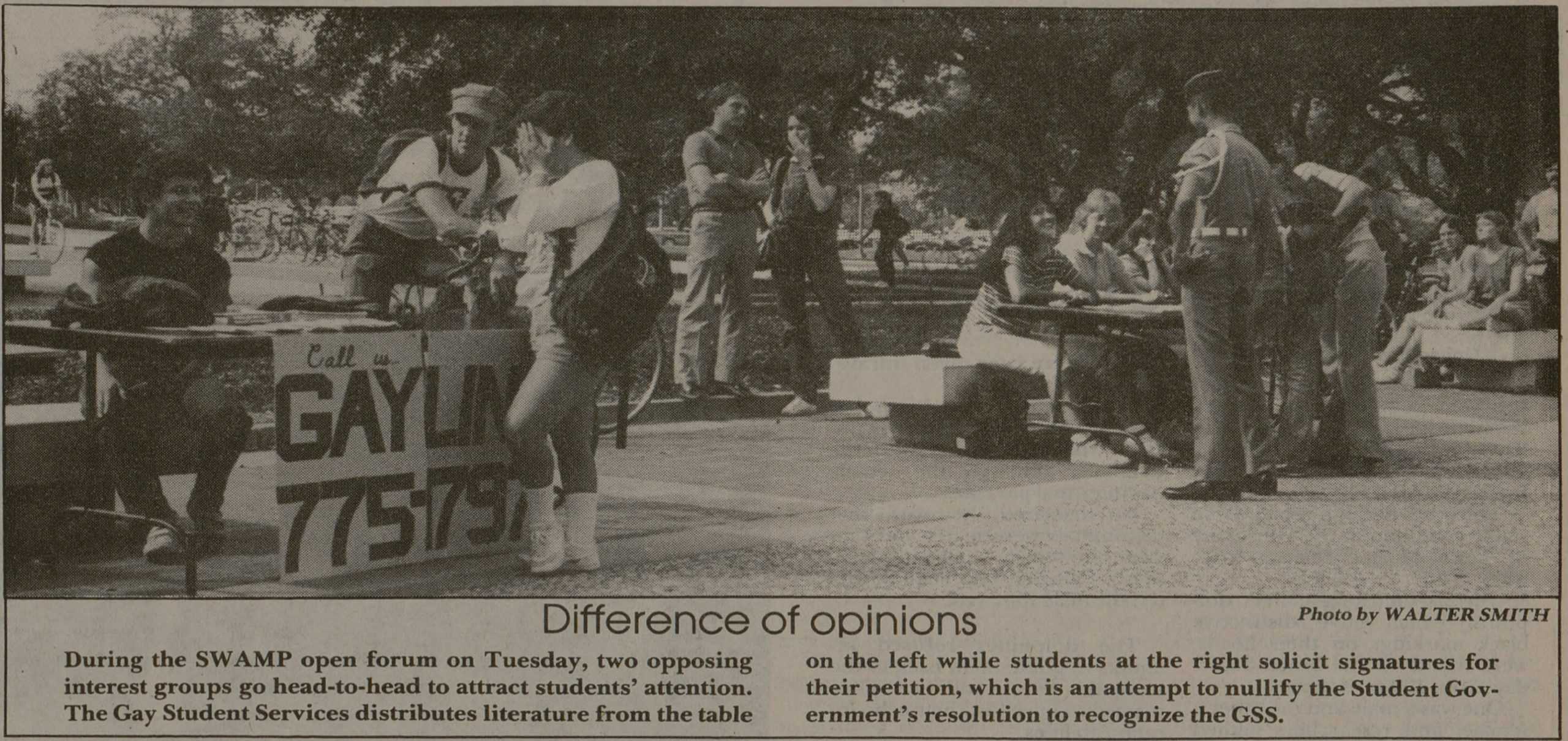

Yet during this time, GSS was pouring its foundation. Their numbers were growing. The gay line was reaching more people. In 1982, they even managed to find a faculty advisor, Larry Hickmann, who was also the faculty advisor for Students Working Against Many Problems, SWAMP. A libertarian organization with university recognition, SWAMP was ideologically allied with GSS, and partnered with GSS to allow them to speak on campus (something they were prohibited from doing because they were not yet a student organization).

(I’ve got a story for you, Ags…

One of the ways GSS advocated on campus was Blue Jeans Day. According to Kevin Bailey, the idea was that, for one day, gay students and their allies should wear blue jeans. The day was meant to get people to think about what it was like for people to think you might be gay. It also forced students who were against gay rights to change their actions instead of gay students changing theirs. Of course, there were letters in The Battalion written by students angry about the stunt. But every year, The Battalion received fewer and fewer letters.)

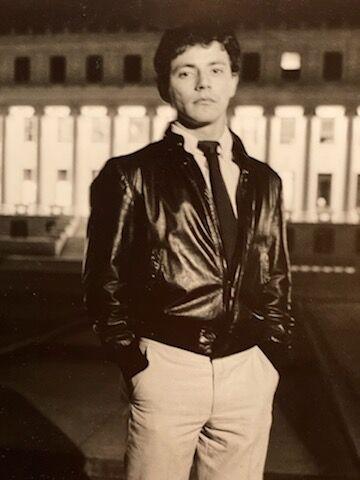

All the while, a new generation of gay students was working its way toward A&M. Time may move more slowly in Texas (and specifically at A&M), but this new generation of gay students was far more assertive in its idenity and much more willing to be in the public eye. Perhaps none would be as influential as Marco Roberts.

Roberts spent much of his early days in Latin America with his father. All things considered, he was able to figure out his sexuality relatively quickly. “I am so gay that there really wasn’t room for question,” he said in a 1984 interview with The Battalion, humorously cutting the tension on campus, much like Sara Herlick before him.

Roberts learned about homosexuality from a book his father gave him about sex. It was clearly meant for a “straight guy,” according to Roberts, but there were discussions on homosexuality that were neutral. While perhaps a far cry from the “It Gets Better” project of 2010, the book told him being born gay was perfectly fine, a fact of life.

“And so, by the time I went to A&M, I was okay with it,” Roberts said in an interview for this package. He had, by his own description, a little bit of a chip on his shoulder, a little bit of an attitude. One thing was for certain, Roberts was not one of Herlick’s “boys in the garage, smoking dope and shaking like crazy.” Roberts was more in the mold of Skinner, Garrett and Herlick. He was willing to be out to the school. And that is precisely what he did.

One powerful moment occurred at a symposium at Rudder Fountain put on by SWAMP. When introduced, Roberts — with that calm confidence which need not exert itself — walked onto the stage, took the microphone and casually sat on a table positioned behind him. He was in complete control. Then, in front of about 100 students who were politely (if skeptically) listening, he said the following:

“I’d like to say that the people who are least likely to get any benefit out of the GSS are the people who join the GSS. By the time you are willing to join this organization, you really don’t need it. You don’t need the gayline. You don’t need the information. You’ve worked it out. We’re trying to reach the people that are scared. And the fact that people are scared is evident right now. We have pamphlets and flyers, and I cannot believe that not one person in this audience is interested to see what we have written down, the arguments to our case. And do you know why? Because you’re afraid. You’re afraid that someone’s going to think you’re gay. Now that’s the kind of ‘freedom’ we’re living in, isn’t it? What a ‘free’ country! Where people are afraid to pick up a piece of paper because of what [the paper] might say in it. ‘What might people think that I’m reading this literature?’ Well, that’s prejudice. And that is evidence that this campus is discriminatory.”

There is little reason to believe this persona was a ploy. One press clipping from the time describes Roberts as one who “enjoys working with weights, swimming, drawing still life pictures and” — perhaps most importantly for Texas A&M’s conservative campus — “supports President Reagan.” (Incidentally, Roberts is currently the chairman of the Texas Log Cabin Republicans.)

Video footage from local news sources at the time shows Roberts — with his well-fitted suits and neatly kept hair — as a clean-cut conservative figure, the perfect spokesman-advocate for a gay student organization at A&M.

In every video clip and photo from the era, Roberts is immaculately put together. Critics of respectability politics might wince at his choice, but this unmistakable mien — the very definition of upstanding Aggie gentleman — sent a clear message: This was not the 1960s. gay Aggies would not be handing out flowers to the Corps of Cadets nor attempting to levitate the Memorial Student Center with their minds. Gay Student Services v. Texas A&M (both the court case and the campus activism) would be Aggie versus Aggie — a contest between two groups on either side of the real old fight.

To this end, Roberts kept GSS on-message in a manner reminiscent of the band commanders who keep the Aggie Band in step. Their cause may have been liberal, but by today’s standards their tactics were undeniably conservative. This choice appears to be borne from three reasons.

The first was the conservatism of Roberts and the libertarianism of Hickman, a political philosophy which meanders from left to right as needed but fits most comfortably in the conservative camp today. The second was that this conservative spin was surely necessary on a campus as entrenched in traditional military and religious conservatism as A&M. Anything else would likely result in abject failure. Third was the court case itself, which after navigating some absurd legal technicalities, could focus on the question of First Amendment rights.

As such, there is little in the public record where a representative of GSS would wax philosophic on the dignities of gay life. Instead, they relied most heavily on a variation of the natural rights philosophy specifically tailored to A&M. Predominately seen in conservative circles, the natural rights philosophy is the argument that rights precede government; it is the idea that all people — men and women, gay and straight — are “endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights,” and that it was the primary responsibility of the government “to secure these rights.”

Such an argument was incredibly beneficial to GSS, for it allowed them, when necessary, to sidestep such demeaning conversations about the gay “lifestyle,” religious views on homosexuality or whether public opinion was on their side. All that was irrelevant. The question put to the student body was quite simply this: Whether or not one agreed with GSS’s message, did they not have the right to say it? And if they did, why was it permissible for A&M, a functionary of the Texas government, to discriminate against GSS on the basis of how they chose to exercise their constitutional rights? Was this a conservative campus or was it not?

If The Battalion’s Opinion pages were any indication, GSS didn’t make too much of a splash. This seemed to be, at least in part, because the court case was being consistently decided in A&M’s favor: Even when the Fifth Circuit had vacated and remanded the case back to the district court, Judge Ross N. Sterling had again decided for the administration. For his money, Koldus was on record in The Battalion as saying, quite plainly, “I disagree with a gay liberation group receiving recognition.”

The willingness to at least tolerate GSS, it seems, was buoyed by confidence that the courts would ultimately decide in A&M’s favor — and that until such time as the judges had had their say, the administration would be doing all it could to assure a favorable outcome.

(I’ve got a story for you, Ags…

To this day, there are some in GSS who feel Judge Sterling was in A&M’s pocket. Given his initial dismissal of the case without comment and his ruling for A&M despite the relative weakness of the school’s arguments, this feeling is understandable. However, outside of the fact that the Judge’s grandfather was a founding member of The Ross Volunteers, there is little to substantiate this belief. Sterling himself didn’t attend A&M, and in Van Ooteghem v. Gray, Sterling wrote in favor of a gay man whose bosses changed his work schedule to prevent him from speaking to government officials on gay rights. Much like Gay Students Services v. Texas A&M, Van Ooteghem v. Gray was decided on First Amendment grounds.)

That sunny outlook changed on Aug. 3, 1984.

Until that point, A&M’s argument in court had been that its denial of GSS’s application had nothing to do with the group’s ideas about homosexuality and everything to do with the university’s long standing policy of refusing to recognize social organizations. The district court had found A&M’s arguments convincing.

That would not be the case at the Fifth Circuit. “We think those findings and conclusions are clearly erroneous and reverse,” Judge John R. Brown noted in his majority opinion.

According to Brown, the assertion that the rejection of GSS’s application was based on GSS’s views on homosexuality was refuted not only by the Board of Regents minutes but the fact that nowhere in Koldus’ letter denying GSS’ application had he mentioned any other reason for rejecting the application. A&M didn’t have just one smoking gun, they had two.

The argument that A&M didn’t recognize social organizations didn’t carry much weight either. A&M had relied on two premises to show that GSS was a social organization. The first was that, before their application was written, Alternative had functioned as a social organization, that the only reason GSS was even attempting to become a service organization was because of A&M’s requirement. This argument may very well be true, Brown wrote. However, it was totally irrelevant. It was perfectly acceptable for GSS to change its mission in order to receive official recognition.

The second argument was that GSS’s failure to take an explicit political stance on homosexuality meant the group must be a social organization. But the Fifth Circuit saw through this as well: Just because GSS wasn’t a political group didn’t ipso facto make it a social one. And besides, while A&M had a history of rejecting fraternal organizations, it also had an equally long history of accepting organizations with purposes similar to GSS’s. Why, the court asked, could the MSC Black Awareness group gain recognition (a group which sought to “promote a better understanding of the heritage and culture of Black Americans”), but Gay Student Services could not? What was the material difference between the Women’s Awareness Group (“a group of women and men who discuss women’s role in society”) and the group GSS was applying to become?

Even the Healy decision made a cameo. Indeed, if “the mere disagreement of the [college] President with [SDS’S] philosophy afford[ed] no reason to deny it recognition,” then surely GSS’s recognition could not be denied purely because “so called ‘gay’ activities [ran] diabolically counter to the traditions and standards of Texas A&M University.”

The Fifth Circuit was calling a spade a spade. This court case wasn’t about social groups. This was about the content of GSS’s message. And as the Supreme Court had said in West Virginia v. Barnette: “Freedom to differ is not limited to things that do not matter much. That would be a mere shadow of freedom. The test of its substance is the right to differ as to the things that touch the heart of the existing order.”

The following week, The Battalion’s opinion pages exploded.

Steve Thomas, a columnist for The Battalion, wrote that “if gays are discriminated against, they should have legal protection” but that “sexuality based organizations should not receive taxpayer money. What about bestiality? What about sex outside of marriage?”

The next day, a letter to the editor citing Thomas’s column posed the following question to the student body: “What if the Bryan-College Station Society for Necrophiliacs wants an organization[al] acceptance, how does the University tell them no and the gays yes? Or better yet, should we have a local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan on campus and enforce all foreign students and blacks to support the organization through financial funding?”

Still another student, in a letter unambiguously titled “Jesus against co-existence with homosexuals,” wrote about his hopes that “the Reagants’ example [would] encourage both the Christians and the students on this campus to continue in their stance against homosexuality and groups which attempt to justify this sin.”

But supporters for GSS didn’t back down either.

One student wrote in to say that Thomas’s column was “absurd” and “offensive,” and that “as a white, presumably middle-class male, perhaps [he] should experience prejudice a little bit before you begin denying rights to those that live with it.”

In response to the “Jesus against co-existence with homosexuals” letter, one student wrote (somewhat humorously, but no doubt seriously) that if Christianity was against homosexuality, then the Star Trek code — infinite diversity in infinite combinations — clearly supported straight students’ coexistence with gay students.

Marco Roberts got in on the action as well. Ever the model of respectability and open discourse, Roberts calmly noted in a 1984 interview with The Battalion that the Ku Klux Klan “differs dramatically from the GSS in that the KKK is dedicated to the denial of civil rights whereas [GSS] is only trying to protect these rights.” Concerning necrophilia, he said, “Homosexual acts require two consenting adults, while necrophilia does not.”

And though the administration quickly appealed the Fifth Circuit’s decision, GSS stuck to their plan. Whether or not most A&M’s students supported recognition, their support was growing. In the courtroom, the administration was on the ropes.

On Oct. 17, 1984, GSS activists scored what was undoubtedly their most significant victory yet.

On that day, a full nine years after the student senate had supported a bill by a margin of 45-15 in support of the university, Brian Hay, the graduate college representative, went to the floor of the student senate and introduced a new resolution. “For too long we have looked inward,” he is quoted as saying in The Battalion. “It’s time to look outward. By recognizing a minority group, they are not enforcing their rule on you.”

The resolution passed by one vote.

And yet even with a victory in the student senate, nothing — nothing — quite captures GSS’s success as the senators’ explanations for their decisions. Without fail, senators who voted against the measure said it was because their constituents were against it. But with the same homogeneity (and indeed, the same passion), the senators who voted in favor of recognizing GSS didn’t mention whether they personally agreed with GSS’s message or not. That didn’t matter. For them, it was simply a question of rights. Gay Student Services had a fundamental right to be recognized, they argued. That right should be protected regardless of how people felt.

The Student Body President would ultimately veto Hay’s bill. Even if it had been signed, the administration almost certainly would have ignored it. But between the Fifth Circuit ruling and success in the Student Senate, the message was clear: At this conservative campus in Middle of Nowhere, Texas — a campus that was, is and forever will be enamored with its own past — GSS was making history.

All that remained was for the Supreme Court to have their say.