When urban and regional planning junior Carlo Chunga’s family’s visa expired, his family faced a difficult decision: Return to Peru where there was job uncertainty and the real possibility of poverty, or stay in America and work for a brighter future.

Like thousands of families around the country with similar stories, the Chunga family chose to stay.

Chunga said there are many misconceptions surrounding people who have immigrated illegally, ranging from questions surrounding taxes to attending public universities.

Chunga said no matter what status a citizen is, no one is exempt from taxes.

“No matter where you live, you’re going to pay property tax,” Chunga said. “We do pay taxes and then we have sales tax. It’s hard to imagine an undocumented immigrant would pay taxes when I look at it from the perspective of citizens — because they don’t really know our story.”

DACA, or Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, made attending college possible for Chunga and other students like him by making in-state tuition available to qualifiers. Communication junior Cinthia Cruz, who crossed the border illegally when she was 10 years old, said DACA is a very selective process.

“Tuition is the same,” Cruz said. “You have to apply [for DACA] every two years and you have to pay a fee of $400 whether you get approved or not. You have to pay for your working permit and the application because they have to do biometrics, like taking your fingerprints, so everything is in the system. We can’t have a criminal record—you have to be an outstanding citizen.”

When industrial distribution junior Noe Ortiz was 5 years old, his teachers gave his grandmother a choice: He could either retake kindergarten or prove himself proficient in reading and writing in English and Spanish in a two-week time frame for a chance to transition into summer school. Today, Ortiz’s grandmother still has his certificate of completion from successfully passing his test, but for Ortiz, the test proved to be one of the easier obstacles he faced as a child.

Ortiz describes himself as an “anchor baby,” or a child born to a foreign mother in a country with birthright-citizenship. This made his parents’ divorce difficult, especially when his father began paying for false testimony, he said. After going into hiding, Ortiz and his family came to Texas to start anew, and much like other first-generation children, Ortiz said he felt the pressure to succeed from a young age.

“It was tough growing up — at least for me. All my uncles and my aunts, they just put this pressure on me and say ‘You’re the man of the house,’” Ortiz said. “The pressure just starts building really quickly, and you have to grow up quickly to the point that I sometimes felt that I didn’t have much of a childhood.”

According to Pew Research Center, as of 2014 there are 11.3 million undocumented citizens living within the nation, and nearly half of all undocumented adults are parents to minors, according to the American Psychological Association. Ortiz said he realized he was different from his peers shortly after moving to Texas.

“It was just different because my mom had to get two jobs and she was probably out of the house, those first couple of years, maybe 16 or 18 hours [a day],” Ortiz said. “I realized that this isn’t something normal because I would see all these kids with all these things and I would ask my mom and she would just have this pain in her eyes — she wanted to give it to us, but she couldn’t afford it.”

However, adapting to American life was difficult not only because of language barriers but also because of a lack of social security numbers. Chunga said that finding ways to adapt proved to be difficult.

“It was hard for my parents to excel because they don’t know English very well so they just took low-income jobs that will hopefully get the family by,” Chunga said. “A few years ago my mom had to stop working due to health problems with her digestive system. That was hard because my family relies on both my parents having a job to get us by, so my dad had to pick up a second job while she couldn’t work. We also didn’t have health care making her medical bills very expensive.”

In addition to legal obstacles, assimilation can make an individual question their identity, Ortiz said.

“I’m trying to prove to Anglo-saxon Americans that I’m just like y’all,” Ortiz said. “I have this accent but I like french fries, I like watching football, I like eating burgers all these kinds of things. You try to prove this point to them like I can immerse myself in your culture but at the same time I have to prove to my friends back home hey I’m Latino I love doing all the things you guys love to do. Most of the time I’m living almost these two different identities,” Cruz said.

Ultimately, Cruz said she just wants to be treated like other students.

“I didn’t choose to come here, but I chose to be an Aggie, and I think that’s the choice that should matter most.”

More than the misconceptions

January 23, 2017

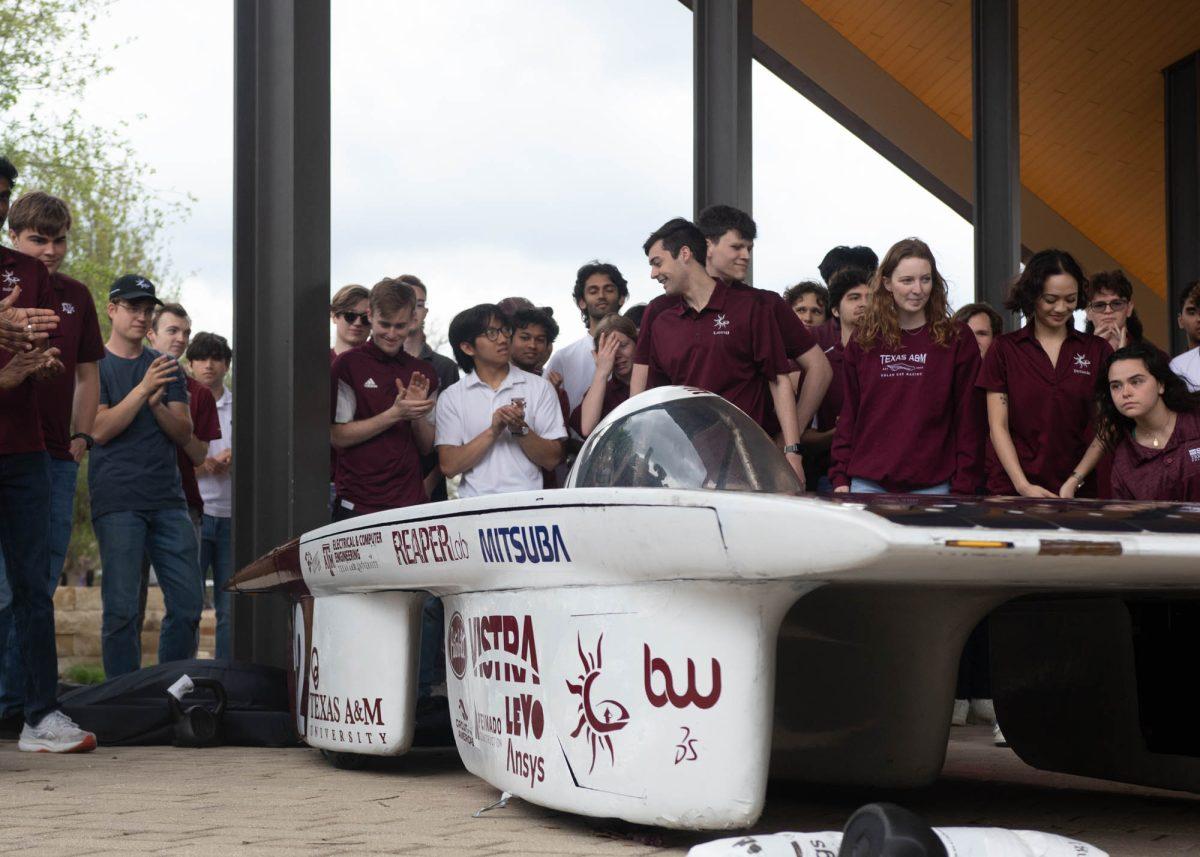

Photo by Photo by Yuri Suchil

Communication junior Cinthia Cruz and urban and regional planning sophomore Carlo Chunga both have parents who immigrated illegally.

0

Donate to The Battalion

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas A&M University - College Station. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

More to Discover