In Paul Thomas Anderson’s 1999 opus “Magnolia,” John C. Reilly’s benevolent police officer shares his life philosophy with the audience as part of his character introduction, stating that as “we move through this life, we should try and do good … And if we can do that, and not hurt anyone else, well … then …” Anderson spends the remaining two hours and 55 minutes of “Magnolia” showing the audience just how difficult that last part can be.

“Magnolia” is about many different things. It is simultaneously a sympathetic parable about the intersectionality of our lives and an intimate look at the vicious, cyclical effects of child abuse. It is the rare film that successfully tells a compelling story with deeply rich characters while also lending itself to an equally rich analysis of its subtext. “Magnolia” does not at any point feel as if it can be solely defined by one of its many attributes. Its story is laser-focused, never wasting time on a moment that doesn’t feel absolutely necessary. And yet, it is in these focused moments that the film becomes universal.

The film follows nine different protagonists, and subsequently nine different plots. While this may seem like an absolutely chaotic and disastrous way to tell a story, all nine characters and their stories are more than adequately resolved. There is a wealthy dying man who is estranged from his son, his young wife who is addicted to various medications and riddled with guilt, a nurse who takes care of the dying man, a young game show-winning genius, a former young genius who was on the same game show years before and is hopelessly in love with a bartender, a terminally ill gameshow host, his cocaine-addicted daughter and the police officer in love with her.

This myriad of characters are constantly colliding into each other’s lives. Their interactions are often due to chance, and the film asks us to consider whether such coincidences could in fact be simply chance or whether there is a divine element at play.

There are no heroes nor villains in “Magnolia.” Instead, every character is unequivocally damaged, most frequently by the actions of another. The innocent are no less subject to punishment than the guilty. In fact, it is the guilty who often possess the most in terms of material wealth.

Unlike other films which explore the injustice of the material world, the cruel in “Magnolia” are seldom forced to relinquish their personal relationships. Instead, it is their conscience which punishes the wicked. Guilt is the source of justice in the film. Guilt doesn’t forget, and regret doesn’t subside with the passing of time.

These are the themes “Magnolia” tackles, and it does so in a profoundly personal way. The film captures the most intimate moments of its characters’ lives in such a way that makes the audience feel as though we shouldn’t be watching. Very few films are able to get to the heart of the human condition in a realistic and convincing manner, but “Magnolia” succeeds in doing so for all nine of its characters. As the official synopsis of the film so succinctly puts it, despite the “multiplicity of plots,” there is “but one story.”

Looking back on ‘Magnolia’

April 28, 2020

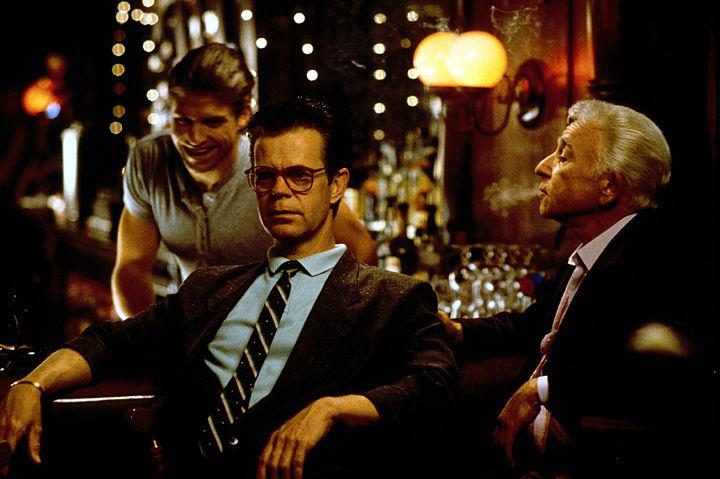

Photo by Creative Commons

The drama film “Magnolia” was released on January 7, 2000.

0

Donate to The Battalion

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas A&M University - College Station. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.