Who would have thought that Netflix would become one of the main platforms for auteur cinema in the last few years? Streaming has allowed film to once again become a more personalized medium for directors who would otherwise have to concede to the 100 to 145 minute template designed by studios to cater to ever-shortening attention spans. Due to the freedom that streaming services offer creators, big-name directors of the past three or four decades have begun to put out some of their most personal and acclaimed work in years.

Last year alone saw Netflix release films by Noah Baumbach (his second Netflix-exclusive film) and Martin Scorsese, as well as the directorial debut of Mati Deop, “Atlantique” (which won the Grand Prix at Cannes, the festival’s second most prestigious award). Scorsese released one of his best (and longest) films to date, “The Irishman,” which runs a whopping three-and-a-half hours and is a somber and deeply personal meditation on mortality and aging under the guise of yet another mobster film. Baumbach’s “Marriage Story” was also nominated for six Academy Awards and its lead performances were acclaimed as some of the year’s best. The Criterion Collection even announced that it would release all three of these films in 2020 on Blu-ray, as they were not released at all on physical media. Prior to 2019, we saw Netflix release an extended cut of “The Hateful Eight” released as a mini-series, and of course Alfonso Cuarón’s beautiful semi-autobiographical 2018 film “Roma.”

It seems as if this trend will continue, because the first notable film of the decade is a Netflix exclusive by a big-name director who is known for his specific visual style.

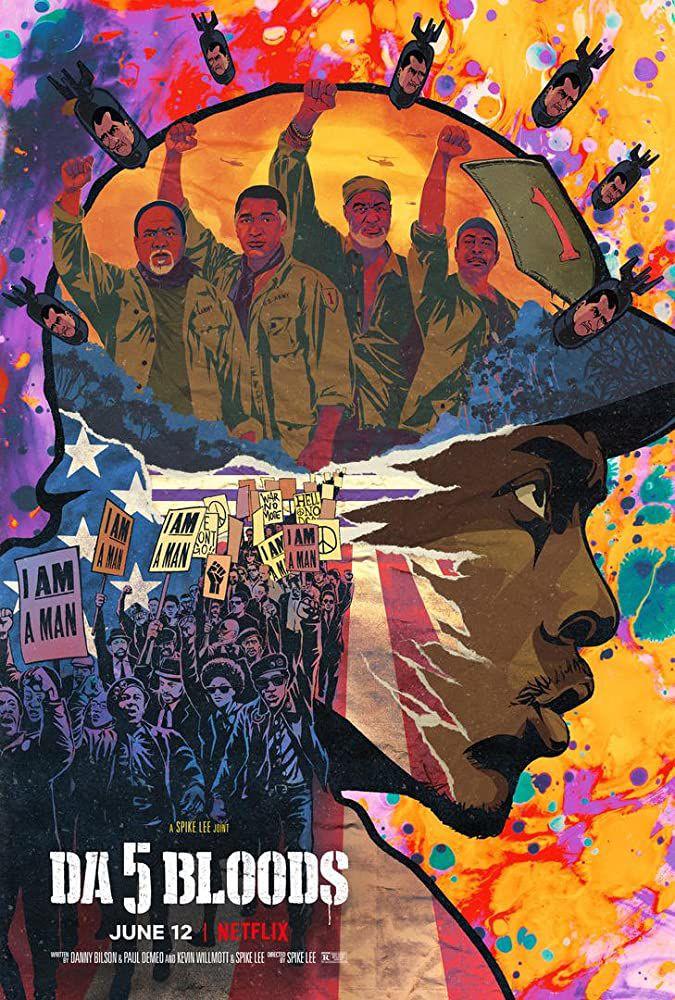

Spike Lee’s work has remained unfortunately relevant. His body of work is a socio-political, yet often highly intimate glimpse into the Black American experience. “Da 5 Bloods” is no different.

The film follows four Black American veterans, the “bloods,” who fought in the Vietnam War. They have returned to Vietnam to retrieve a large amount of gold that they buried when they were there as young men, fighting for a country that only valued them as cannon fodder. The film informs us via radio broadcast aimed directly at Black soldiers fighting in Vietnam that while only 11 percent of the total American population is Black, Black men made up 32 percent of Americans fighting in a foreign land. The radio broadcaster challenges these men about whether or not this ratio is just.

The conflict between fighting a war abroad while the real fight is back home is one which resounds throughout the entire film. It justifiably breeds deep resentment and anger within the hearts of the bloods, who wish to recover the gold as a form of reparations for every Black person in the United States of America since 1619 who has been trampled and dehumanized. Two of the bloods, Otis and Eddie, want to donate their portions to the cause, to organizations which will benefit Black communities. Paul and Melvin don’t see the need to do so, and would rather keep their portions for personal use. This tension between survival and obligation to one’s heritage is one which permeates not only through this film, but much of the director’s work.

The standout performance is that of Delroy Lindo as Paul, a man who is self-admittedly damaged, possibly irreparably. He has deep guilt over something that happened to another soldier, a young man whom he deeply admired and saw as the best of them (“Stormin’” Norman, played by the great Chadwick Boseman) during their time in Vietnam. His main reason for returning to the Vietnamese jungle is to reconcile with his past, but more importantly with himself. Paul is deeply flawed and often unlikeable and has a strained relationship with his son, whom he feels he is incapable of loving. Paul is completely broken, and suffers from extreme PTSD. Lindo’s performance is one of the most riveting and complex portraits of PTSD on film.

The rest of the cast is also excellent, and the true heart of the film is found in their comradery and deep love for one another.

The cinematography is gorgeous, especially the scenes which take place during the war. These sequences, shot on 16 mm film by the great Newton Thomas Sigel, are incredibly vibrant, lush and warm. Because of them, this film begs to be seen on a giant screen. The war scenes are masterfully shot, with Lee utilizing handheld and tracking shots to maximize coverage without losing the visceral perspective.

The film is not perfect, however. While the leisurely pace of its two-and-a-half hour runtime is refreshing at times, it could easily be trimmed down by fifteen or twenty minutes without any loss of potency. There are also several major unnecessary plot conveniences which could have easily been avoided.

Despite these flaws, “Da 5 Bloods” is a triumph, and points to an ever-increasing climate of filmmaking which once again values creativity and personal vision.

New Spike Lee film ‘Da 5 Bloods’ is a triumph of personal, meaningful cinema

June 29, 2020

Photo by Creative Commons

“Da 5 Bloods” released on Netflix June 12, 2020.

0

Donate to The Battalion

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas A&M University - College Station. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.