In the season one finale, “I Dream of Jeannie Cusamano,” an exasperated Tony Soprano, engulfed in a minor mafia war, explains to his wife where things went wrong.

“Uncle Junior and I, we have our problems with the Business,” Tony says, referring to the crime family he and his uncle oversee. “But I never should have razzed him about eating p****. This whole war could have been averted. Cunnilingus and psychiatry brought us to this.”

Such was the exceptional writing of “The Sopranos.” Witty and dramatic, pornographic yet subtle, light on its feet while unflinchingly dark, that line accurately captured a season-long plot Shakespearean in its depth of character, its intricacies, its sheer absurdity. What begins with a joke about an old, prideful man pleasuring his chatterbox of a girlfriend ends with several dead mafiosos.

But times have changed since 1999.

We now know more about toxic masculinity. Psychiatry has lost much of its stigma. Harry Styles has released an anthem-cum-humblebrag about which Uncle Junior would be proud — and which might send Tony into another tizzy about the nature of modern-day masculinity.

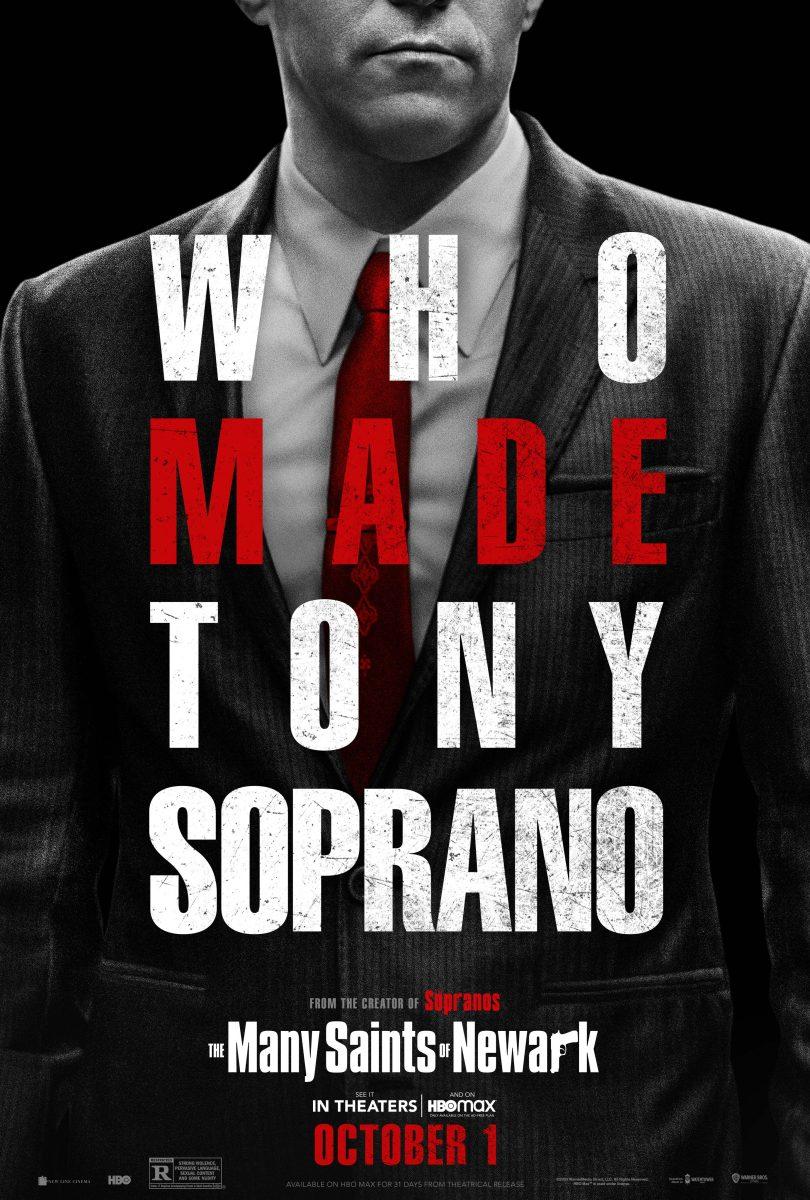

So the challenge for “The Many Saints of Newark,” a prequel to what is undoubtedly the best television series of all time, was always going to be two-fold: First, how to make the film as relevant today as its predecessor was during its initial run. Second, how to balance the necessities of a character-driven prequel with storytelling that is, in turns, magnetic, titillating, insightful and, above all else, coherent.

Those are high standards, to be sure, but they are the standards “The Sopranos” set for itself over six seasons — and by and large surpassed.

This current outing is directed by Alan Taylor, and written by Lawrence Konner and series-creator David Chase, all of whom cut their teeth during “The Sopranos”’ original run. The film is passable, but the trio seem to have lost a step since 2007, when their show famously snapped to black.

Start with the good. The film wisely focuses on Dickie Moltisanti, played by Alessandro Nivola, father to fan favorite Christopher and uncle to Tony. Dickie always hung over the series as something of a ghost — wistfully remembered but never seen, an impactful figure in Tony’s life but a man that Christopher never quite knew. At times, he seems to speak to the characters as if from underneath a funeral pall. Because Dickie is dead before “The Sopranos” pilot takes place, exploring his life is fertile ground for a prequel: Fans know enough about the character to be intrigued, but not so much that the writers are hemmed in by anything they’ve already written. (Incidentally, this is why, narratively, “Rogue One” is the best Star Wars prequel. We know the team gets the plans for the Death Star; we know they die along the way. As long as the story hit those main points, the writers were free to go in whichever direction they liked.)

Chase and Konner don’t squander the opportunity, but neither do they maximize its potential. No doubt some of this is due to the medium. “The Sopranos” original run had 86 episodes, each lasting between 46 and 75 minutes. That’s plenty of time to explore the psychology of a sociopath who walks into a psychiatrist’s office. By comparison, Dickie is only given a couple of hours.

Still, aside from some anger issues for which he appears (possibly? maybe?) remorseful, Dickie has little depth. He starts out nebbish enough but is quickly revealed to be — spoiler alert! — a mobster capable of killing people. It isn’t groundbreaking material for a mob movie. And for “The Sopranos,” it’s downright average, something fans would have expected to see while the plot steadily built to something bigger. In contrast, there is little insight in “Newark’s” violence. It has all the delicacy of Styles maniacally chomping into a watermelon.

The side characters don’t fare much better. Corey Stoll and Vera Farmiga do an excellent job evoking the spirits of Uncle Junior and Olivia Soprano, Tony’s overbearing mother. But characters such as Paulie, Sylvio and Carmela are relegated to brief cameos punctuated with a dissonant, “Thanks, Paulie” or “Bye, Sylvio” before never being seen again. These winks and nods at the audience aren’t just jarring, they’re fan service, a level to which “The Sopranos” never allowed itself to stoop.

And Tony? The mob boss who once had a panic attack after watching a flock of geese fly away? He’s here too, but more than he needs to be. The fact that Tony was born into a crime family — that as he tells it, he never had a choice but to join — was well established more than a decade ago. But “Newark” offers little new or interesting in Tony’s backstory. We see it happening. That’s it.

Which is unfortunate. We spent eight years poking and prodding the psyche of Tony Soprano. But in two hours, “The Many Saints of Newark” reduces him to something of a crude appendage.

And really, that tells you all you need to know about the film’s shortcomings.