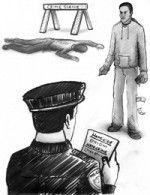

On April 1, Broderick Hehman, a 20-year-old New York University student, was attacked by five men attempting to rob him. As he fled, Hehman was struck by a car. He died three days later at Harlem Hospital.

The New York Sun reported that eyewitnesses heard the five attackers, all African-American teenagers, shout “Get the white boy!” while pursuing the student. Prosecutors also claim that the attackers did not call for help after Hehman was struck, but instead stood aside and laughed while the tragedy unfolded.

The New York Hate Crimes Act of 2000 claims that victims that “are intentionally selected, in whole or in part because of race” are victims of hate crimes. Hate crime charges are determined by the opinion of responding police officers, not the deliberation of a court.

In the case of Hehman’s death, it was the responding officers’ opinion that the crime was motivated solely for “economic reasons.” Because of this, the alleged robber-murderers will not be charged with hate crimes. This is a nonsense method for determining guilt and should instead be left up to courts to decide.

It is the job of police officers to take the facts of a crime and turn them into criminal charges. Determining the possibility of a hate crime forces the officer to step out of his or her role and become a psychologist. The factors surrounding a criminal’s motive are often legion and cannot be accurately determined on scene with insufficient background on the perpetrator. When dealing with other crimes, motive is left for a jury to decide and only after deliberation by both sides. Current policy has created a one-man court, playing the part of arrestor to executor and everything in between.

This is a polarized issue, but it is not just about black-on-white crime or white-on-black crime. Hate crimes cover an entire spectrum, including race, color, ethnicity, age, religion, gender and sexual orientation. It would be foolish to think that all of the officers involved are completely free of prejudice. One may argue that juries may have their own prejudices, but there are two major differences: Juries are often selected with diversity in mind, and they are exposed to extensive deliberation concerning the issue.

Also, remember that these officers are members of the community upon which they are passing judgment. Police may be reluctant to incite racial tensions in areas that they would later have to deal with. Jurors are often given a measure of anonymity, but police officers are very visible on the street. People discontent with hate crime decisions could accuse police of bigotry, and destroy their reputation – or worse, target them for violence.

The issue of interpreting law and motive should be the court’s responsibility. Hate crimes spark controversy and can create a lot of angry, indignant people in a hurry. Given this, the justice system should do everything in its power to ensure proper attention is given to every issue. The current method of charging hate crimes ignores the very nature of law and due process.

Misplaced jurisdiction

April 23, 2006

0

Donate to The Battalion

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas A&M University - College Station. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

More to Discover