Drought is the main driver behind 10 years of U.S. wildfires plaguing forests while devastating communities, upending economies and lives.

Recent wildfires in California and Texas that are larger and expand rapidly offer clues that researchers have said can lead to better practices for containing — and controlling — future fires.

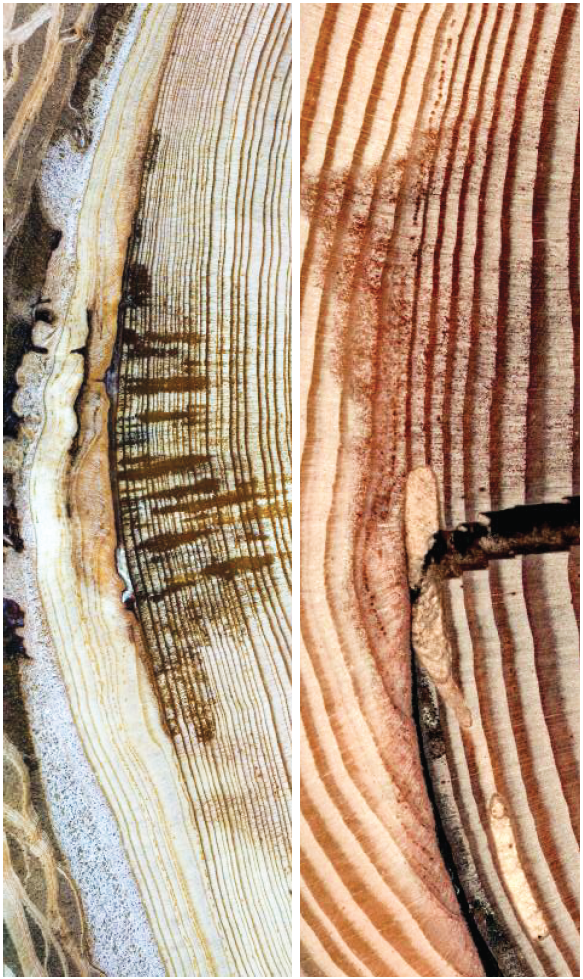

Tree rings and landscape scars explain fire trends, explained Charles Lafon, professor of geography at Texas A&M. Tree rings with less scarring show how the trees were able to heal following wildfires before being cut down, he said. These scars also show that while the number of wildfires hasn’t increased, the size and scale of fires has increased, Lafon said.

“The last few hundred years, I’d say, we’ve had fires that occurred frequently over most of the continent until about a century ago,” Lafon said. “They more or less stopped. Despite what you hear on TV, there are a lot less fires than there used to be.”

Drought is the main cause of wildfires, and historic drought conditions over most of the Western U.S. has created the perfect storm of dry conditions to spread flames, said A&M atmospheric sciences professor Yue Zhang, Ph.D.

As drought drives fires, current practices of not allowing natural wildfires to burn interrupts nature’s cycle. It might seem responsible, but it makes wildfires more intense when one does spark, Zhang said.

“That will essentially cause more and more material for wildfires to be building up, then it’ll inevitably cause a large wildfire that’s going to be out of our control,” Zhang said.

More intense flames and heat create more air pollution, Zhang said.

“Air quality in any region where the wildfires have happened will deteriorate for a long period of time,” Zhang said, “so that could cause potential health implications for people living in the surrounding areas.”

Lafon said repeat strikes cause lasting damage even when the wildfires are years apart since multiple wildfires don’t give the land enough time to heal.

Considered the most devastating wildfire in Texas history, the 2011 Bastrop County Complex lasted over a month, destroying 1,600 homes and burning tens of thousands acres, according to a report by Austin NPR Station 90.5. An estimated 1,700 trees perished.

“When you get a severe fire like that, you get a whole cell change in the vegetation,” Lafon said. “The forest doesn’t recover very quickly. The imprints of that fire can be on the landscape for a century or more.”

It takes hundreds of years for nature to restore itself, Lafon said, but with fires continuing to burn, it can’t heal. Habitat loss and extinction of some species in the area follows, Lafon said.

This fall, Colorado is experiencing its first out-of-season wildfire as spring is normally fire season. As the second largest wildfire in Colorado history, Este Park firefighters are hoping predicted upcoming snow will help extinguish the flames, as reported by The Washington Post.

Out-of-season wildfires might be a new trend due to current increases in climate change, Zhang said.

“I would even expect in the long term, as long as we still have global warming and climate change, out of season fires may still increase,” Zhang said.

Research that began in October at A&M is aimed at finding solutions for safe and cost-efficient fuel treatment. The project is examining how planned vegetation removal has potential to stop wildfire spread, department head of Industrial & Systems Engineering Lewis Ntaimo said.

Timing of treatment plans in a given area, why wildfires occur in the region and how vegetation changes over time are all being studied, Ntaimo said.

Now more than ever, Ntaimo said people should pay more attention to the true costs of wildfires and work together to prevent them. Simple, important steps include following local burn bans and reporting a fire when first spotted before it can spread, Ntaimo said. Being able to prevent these wildfires in the future can save homes, land and the many lives of those that fight against these flames. Prevention can also save counties and residents money that would’ve been spent on repairing damages.

“There’s a huge economic incentive to actually do something about [wildfires],” Ntaimo said. “And that’s why people should be aware of this and realize that it affects everyone.”

This story is a collaboration between The Battalion and upperclassmen in Texas A&M’s journalism degree. To see the online copy of the Climate Change extra print edition, click here.