The majority of students graduating from college seek a job post-graduation; approximately 77 percent of the 1.2 million 20-29 year-olds who graduated in 2017 looked for jobs, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. However, there is a pay gap which can affect individuals’ salaries based on sex, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, race or age, according to the American Association of University Women (AAUW).

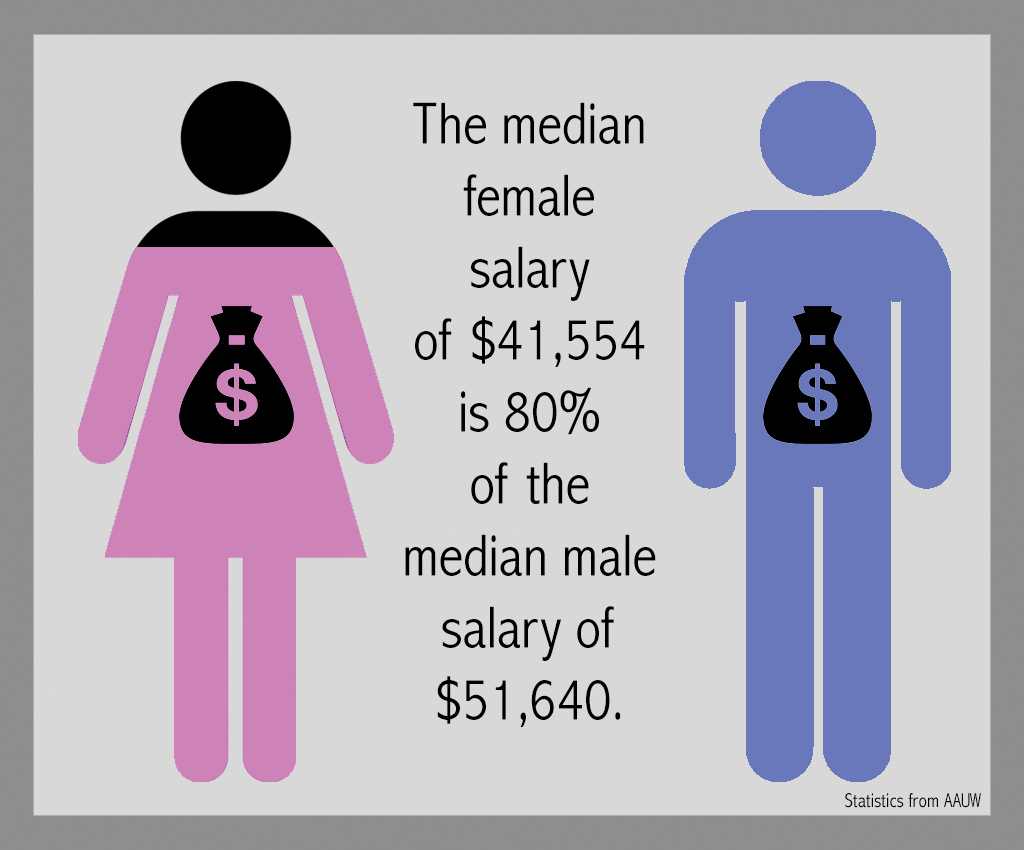

The pay gap, as defined by the AAUW, is the difference in men’s and women’s median earnings. In 2016, the earnings ratio, calculated as the difference between women’s median earnings and men’s median earnings, was approximately 80 percent, meaning the pay gap was approximately 20 percent. Although both men and women’s earnings increase over time, the pay gap grows with age; there is a 22 percent difference in earnings compared to a man’s salary between women aged 18-24 and women aged 55-64.

Melissa Ochoa Garza, sociology Ph.D. candidate, is completing a project for her dissertation studying observations of everyday sexism.

“Essentially … we’re trying to create a theory that explains how sexism is systemic,” Ochoa Garza said. “So in order to do that, we have to be able to find the dimensions of the daily types of sexism that happen that are accepted and are normalized, and then be able to say how those micro-level interactions are representative of a larger system of oppression.”

Chika Nwachukwu, allied health senior, works in Ochoa Garza’s research lab. Nwachukwu said there is often sexism in the workplace where men will dismiss women from conversations, which she said she thinks could contribute to the lingering pay gap.

“Women in male dominated fields, they feel often times ignored because usually the men try to shut them down, try to exclude them from the conversation, they try to silence them, they try to interrupt them, they are basically dismissed,” Nwachukwu said. “A lot of women, unfortunately, they internalize it. They become silent, they don’t fight it.”

There is a sex segregation in the workforce, meaning women tend to work in lower paying jobs, according to data collected by FiveThirtyEight. Statistics show eight out of the 10 lowest-paid professions are at least 40 percent employed with women, while only four out of 10 can be said of the highest.

“Predominantly female careers are going to be paid less because they’re careers that are seen as unproductive by society,” Ochoa Garza said. “So that’s like teachers, nurses, caregiving roles.”

Ochoa Garza said from a sociological standpoint, there is more to this issue than meets the eye. The socialization of the sexes is often different, which could be a factor in this sexual segregation of professions.

“While many people would say, ‘That’s a choice, women get paid less because they’re choosing those jobs,’ as sociologists we say, ‘Well, wait a minute, let’s back up,’” Ochoa Garza said. “Let’s look at socialization, let’s look at the kind of messages women are getting and the way they are being treated when they express interest in things that are not considered feminine or for women.”

Haley Peters, interdisciplinary studies senior, works as a tutor and will be a full-time teacher in the fall. She said she has not experienced a pay gap due to the set salaries all teachers start with, but is aware of her profession being predominantly female.

“Caretaker jobs or teacher jobs are a majority women and those are very lower-paid scale jobs,” Peters said. “It’s just like engineering or medical engineering are male dominated and higher pay.”

Samira Choudhury, biomedical sciences senior, will take a gap year before going to medical school. During her gap year, she said she hopes to work for a non-profit specifically directed toward women’s health, or anything directed toward helping women and girls.

“Obviously I think [equal pay is] a necessity in any career field, whether you’re a college graduate or not, but specifically for college graduates,” Choudhury said. “You have two groups of people who are going through the same curriculum … they’re going through the same rigor for four years, they’re faced with a drastically different response from employers. I feel like that’s really discouraging for people. So then that sentiment gets passed down and that can potentially discourage other females who are being disadvantaged.”

Another layer to the pay gap is race and ethnicity. According to the AAUW, full-time female workers in 2016 who are Hispanic or Latina, American Indian or Alaska Native, black or African American and Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander had lower median annual earnings compared to non-Hispanic white and Asian women, with Hispanic women having the largest pay gap of 54 percent of a white man’s earnings.

“There’s this gender gap that people always talk about,” Choudhury said. “I think a lot of people don’t realize that’s between white males and females, and so the disparity from the highest level is like the white male and then women of color is even lower.”

Choudhury said it is important to her that everyone is equal, making it crucial to recognize that there is a clear pay gap between more than just gender.

“Obviously I want everyone to be equal, but that to me is even more of an issue because … it’s including more than one type of prejudice into the mix,” Choudhury said. “So you’re having those two things affecting people’s livelihoods. I also am a female of color. I don’t want to have to go through four years of hard work to have to be put down below two other categories of people when we’ve all done the same thing.”

The state of the pay gap

May 6, 2018

0

Donate to The Battalion

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas A&M University - College Station. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

More to Discover