They’re still there.

The wishes and prayers and the sadness, all of it’s still there. People call out to him; they come to leave letters of friendship, grief and love. He lingers in their hearts, his time on Earth an ephemeral testament to joy and pain and the frustrating mystery that is life.

Oct. 16: five months after he departed, there were four messages to him posted on the Facebook page that, like the untold numbers whose lives he touched, he left behind. Five more the next day. There’s always something new, someone who still searches for a way to cope without such a positive force in their life.

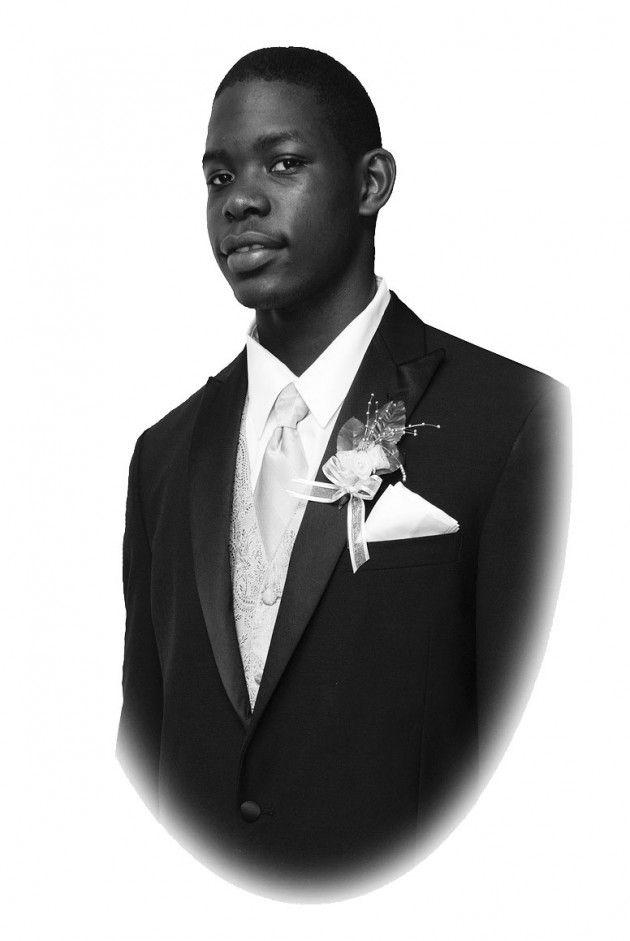

Michael “Tobi” Oyedeji, 17, died May 16 after sustaining grevious injuries in a head-on car collision, but they’re still there.

One would imagine that he is, too.

Beyond his years

It’s the summer of 2009 and the gangly teenager gallops along a basketball court with the world in front of him.

Years of recruitment, months of deliberation and countless prayers and discussions with his parents have carried the young man — six feet and eight inches of roaring enthusiasm and boundless potential — to the most monumental decision of his life. The arms that make up his seven foot four inch wingspan churn alongside him. His booming voice rings out across the floor.

His smile lights up the room.

“From the first time that I’d ever met Tobi, the first time he ever came to this campus — it was probably as an eighth-grader — he was different,” said A&M Athletic Assistant Dustin Clark. “His basketball skills notwithstanding, he was a big-time kid. His personality shone through. The day he committed, he was so excited to be an Aggie … I remember him just running across the gym floor saying, ‘Hey Coach, I did it! I did it! I did it!’ and I said, ‘What are you talking about?’ He said, ‘I committed, I’m going to be an Aggie!'”

Oyedeji, born May 21, 1992, was the only child of Mike and Nikki, both Nigerian-Americans. As a middle schooler, he played the saxophone before letting it go to focus on schoolwork and basketball. Before his freshman year of high school, he was selected from a pool of more than 1,000 applicants to attend Michael E. DeBakey High School, the No. 1 public school in the Houston Independent School District. DeBakey did not have an athletic program. With acceptance considered an honor, a student declining an invitation to attend was unthinkable.

Yet Bellaire High School called the Oyedejis to offer Tobi a spot. Citing the school’s academic profile — while not quite DeBakey’s — alongside an opportunity to play basketball, he made the decision to switch to Bellaire.

He loved basketball, but academics were just as important to Tobi. Those close to him adamantly referenced his priorities.

“So self-motivated,” Michael Oyedeji said of his son. “He was up late many nights studying and doing homework. He drew his own line with basketball and high school.”

The school counselor once told his parents that if everyone was like Tobi her job would be so easy. Tobi knew, as his father assured him, that if his grades slipped there would be no basketball.

Still, he worked his way to academic success with little prodding or intervention. He intended to take full advantage of his time at Texas A&M; during his recruiting visit, he insisted on meeting with advisers from the college of engineering.

The High School Academic All-American Game invited him to join the American roster after his senior year based on meeting qualifications that included GPA, SAT/ACT scores, strength of high school curriculum, college selection and other extracurricular activities. He flew to Azusa, Calif. for the game.

He returned with the Player of the Game trophy.

“He was a very intelligent kid, very bright,” A&M Head Coach Mark Turgeon said. “He loved basketball. He was very passionate about basketball. Always had loved it. Played harder every day, more than any player I’ve ever recruited. You knew one thing when you went to watch Tobi: that he was going to play hard. And he did that consistently. Because of how hard he played and how driven he was with basketball, he was really just starting to scratch the surface of where he was going to be as a player.

“I think he would’ve left here with a degree. He wanted to play [in the] NBA, like all kids do, but Tobi was going to be very successful in life with or without basketball.”

The time of their lives.

It’s noon on May 15; the sun sits high overhead and Ray Turner is grinning ear to ear as he meets Nikki Oyedeji outside a fabric shop in Bellaire. As a fellow post player from Houston and a cog in the Aggie program, he has grown to be a surrogate older brother to Tobi while his recruitment plays out. Prom approaches quickly, littering every youth’s mind with the euphoria only a night that seems as though it will last forever brings.

The Aggies’ then-freshman forward embraces her, envisioning just that. It will be the time of their lives — before the responsibility. Before the worries.

“Tobi’s so excited!” she says. “When you get together, you will have so much fun. I want you to have fun.”

Turner smiles again.

“We will,” he responds. “I’m gonna make sure Tobi has a wonderful prom and take care of him and make sure everything’s alright.”

‘On my way home’

Turner departed shortly after to pick up his girlfriend and meet Tobi. The two friends laughed and played that night, danced and sang and joked beneath the lights. They talked about life and love and college. They posed for pictures. Turner thought about his plans for surprising Tobi on his birthday, which was six days away, and about playing with him at A&M.

“He was just so excited he didn’t know what to say,” Turner said. “He was just like, ‘Man, I so cannot wait.’ It was wonderful. I’ll never forget that night.”

At the prom’s conclusion, they left with their dates to visit Dave & Buster’s for the after-prom festivities. A duel at the basketball-shooting booth followed food and games. They agreed to take their dates home at about 2 a.m. when the two fatefully parted ways.

“I know he was [with his date] for a while, then he left from there around 4 or 5 a.m. on his way home,” Turner said.

Tobi did not drive often; Mike and Nikki weren’t planning on giving him a car until after his first semester at A&M. They didn’t feel right about letting the night of their son’s prom pass without him being able to go where he pleased, and still insist they feel letting him borrow a car was the right decision. When he left his date’s house and went out into the world for a final time, he sent his father a text around 5:55 a.m. to check in.

“Dad, I’m on my way home.”

Just after 6 a.m., the car he was driving lurched across a median when — it’s assumed — he fell asleep at the wheel. The head-on collision killed 52-year-old Gertha Augustin, an MD Anderson nurse, at the scene and sent Tobi to Ben Taub General Hospital with severe injuries. Through Bruce Glover, the coach at Bellaire, Turgeon, Clark and the other A&M coaches were notified of the accident and immediately headed to Houston.

Of all people

Turner pauses, hunching forlornly on a bench in the Cox-McFerrin Center for Aggie Basketball.

“I’m on my way home. That was the last message he sent to his father,” he says. “That was just a big sign for me.”

Tobi’s parents nod with a faint smile when asked about the text. It’s still so hard for them to revisit, but there are no doubts.

“When he sent that, he wasn’t talking to us anymore,” Nikki says. “We know that at that point, he was beyond us. We know who he was talking to.”

That doesn’t make it any easier.

Tobi planned to room with freshman Daniel Alexander during the first year of school after they became friends in the travel team circuit and during the recruiting process. Alexander sits across from Turner, shaking his head.

“I just cried for a couple hours without talking to anybody,” he murmurs. “It didn’t seem like there was any reason for it. Hard worker, always gave the glory where it was due and played to contribute for his team, not for himself. He never did anything stupid, never put himself or others in danger. It made me ask, ‘Why him? Of all people?’ I still struggle with that.”

All eyes trail to the floor.

A tearful Turner rocks slowly on the seat, whispering to himself.

“He should still be here.”

Disbelief

It’s been five months and Clark sits in his office with solemn eyes trailing to the ceiling.

“I’ll never forget, I got a call Sunday morning, the 16th, from his high school coach, and he said, ‘Tobi’s been in a car wreck,'” he says. “And I said, ‘Is he OK?’ He said, ‘Well, he’s in the hospital.’ I jumped in the car and drove to Houston and I had heard that his injuries were [bad], that he had some internal bleeding and he was in surgery and had some broken bones. At that point in time I knew he was in bad shape and the thought crossed my mind that he might not ever play the game of basketball again — and I was fine with that.

“I was OK with that; I just wanted him to be able to come to Texas A&M and have a normal college career just like every other college-bound student and go forward from that.

I was OK with that as long as he was OK.”

Clark joined Mike and Nikki in the ICU waiting room. Together they prayed and hoped. They embraced. They waited.

“The surgeon came in and said, ‘Where are the parents?'” he recalls. “And he said what you never expect you’ll hear in your lifetime. He said, ‘We’ve got Tobi out of surgery and we’ve done everything we can do, and his chances of survival are very low.'”

The small contingent moved together into the ward where Tobi was housed and stood with him for nearly 10 minutes as the last sands of the hourglass slipped away.

Turgeon was mired in flights between California and Dallas throughout the day but said, “I left [the family] a message again, tried to call them again that night, didn’t get through to them, planned a trip to go see them the next day. It happened quick. You don’t ever expect it, and when you’re dealing with a guy like Tobi you’re like, ‘Yeah, he’s in an accident, but he’s a big strong kid, he’s gonna survive.’ It was tough. It’s still tough. It’s still really hard for us.”

With his hands covering his eyes, a quiet Clark leans back in his chair and concurs.

“I still didn’t think we were going to lose he was that tough. That’s something else about Tobi, the toughness about him. I just thought he was going to pull through.

“I said something to him, but…” The sobs take over. Eventually he mutters, “I don’t know if he heard me.”

A life of love

It’s Oct. 25 and Nikki Oyedeji rests lightly on the couch in her home in Missouri City. Filtered light seeps through the curtains, splaying delicately across the shrine that fills the foyer. Framed jerseys, awards, pictures, posthumous honors and cards drape the wall. It’s a bittersweet smile that draws across her face when she looks at it.

She keeps her spirits high nonetheless, and offers a plate with cashews and chips. They’ve got a kick to them.

“Tobi loved spicy things,” she says wistfully.

Tobi loved a lot of things. He loved God. His favorite catchphrase, which he doodled everywhere and which still hangs above his bed, was “Man can’t control my destiny.” He carried a devotional everywhere with him and dedicated ample time to studying it. Nikki opens the book to show highlighted phrases on every page from Jan. 1 to May 15. During Tobi’s trip to California, Mike called him late at night to check on him. He answered and told him abruptly that he would call him back.

“I’m reading my devotional,” Tobi told his father.

He loved gospel music and playing guitar. He loved his family and friends. Without fail, coaches and teammates alike spoke of how much love existed between him and his parents, his respect for them and how proud he made them. He called everyone his friend, even if he’d only met them once. Mike described being with him in a mall and having to stop repeatedly so he could visit with each person who wanted to talk to him. “Oh, that’s my friend [so-and-so],” Tobi would say.

His room is just as he left it. Dollar bills and spare change sit atop the dresser. An iPod Nano rests in its charging dock. His clothes still hang in the closet and his Xbox 360 lies below the television. It all projects the image of an average 17-year-old student.

He was more than that.

“He loved Texas A&M and he was gonna be a great ambassador for this place … He was a big, lovable, super-positive kid,” Clark says. “He brought energy to a basketball floor, he brought energy to a room when he walked in. He was a really high-character kid. He was very grounded and he had a belief system. He was going to be somebody that was easy to be a fan of. A lot of parents would’ve wanted their kids to be fans of Tobi because he was that kind of person. When you think about what an Aggie is, that’s what Tobi was. A hard-worker, had a value system, wanted to make other people’s lives better. He was loyal. He had a great spirit about him.”

Tobi’s greatest ability was his way of bringing people to him and leading them by example.

“For his age — he wasn’t even 18 — to touch as many lives as he touched … Tobi was one of those kids, at a very diverse high school, who got along with the popular people, got along with [everyone],” Turgeon said. “If he had ran for class president I’m sure he would’ve gotten it. He made everyone feel so special. There’s a story about a freshman girl who dropped her books and was so nervous and he bent down and picked them up and made her feel like a million bucks. There are a ton of stories like that. And that was just Tobi. I remember seeing a kid, when I went by the school that day, who was just torn up, a freshman or sophomore who was about a foot smaller than everyone else, and you just know Tobi made him feel so good every day when he talked to him. I don’t think he had any enemies. I don’t think he ever cursed in his life. He just touched a lot of people in a positive way.”

A package arrived for the Oyedejis not long after Tobi’s death. It was addressed from the young man who was Tobi’s roommate in California during the All-American game. Inside was a pair of $300 “Beats by Dr. Dre” headphones and a note explaining that Tobi had broken his headphones in the airport in California; he made such an impression on his roommate that the young man decided to buy him the new ones, but never got to send them before the accident happened.

He wanted the parents to have them anyway.

“Tobi was very humble, very cool to be around, always chill,” Turner said. “Tobi was funny, a character. Really a character. Always joking, always enjoying himself, having fun, very Christian-like. Tobi was wonderful. He was the perfect kid. You cannot not remember Tobi. He was goofy and crazy, in a good way. It’s like he was blessed with not just talent and his ability to be a great basketball player, but he was also blessed as a person. One of a kind. It was unbelievable.”

The smile returns to Mike and Nikki’s faces when they relay anecdotes about what made their son so unique. They unroll a 20-foot-long sheet of paper on which students from Bellaire wrote to Tobi after the accident. They show letters from people across the nation whose faith and lives Tobi impacted, whether or not they knew him.

“He influenced people without much effort, just by being himself,” Mike says. “The legacy he left behind is already spreading.”

Clark nodded knowingly at the mention of the Facebook posters.

“It’s tragic any time a young person is taken from the world, but Tobi was special, because of the people that he impacted,” he said. “They saw the way that he lived his life.

He didn’t have to say anything to you and he made you want to be a better person.”

An older woman approached Nikki the day of Tobi’s death to ask if she was his mother. When she replied yes, the woman told her she had raised a wonderful boy. She had nothing else to say.

‘Only the good die young’

Crying on that lonely bench, Turner puts his head in his hands and waits for the words to come. The seconds pass as though hours; life slows to a halt in a quiet hallway. What was and what could have been drift through the air. Time does not seem to flow.

Turgeon referenced Billy Joel’s “Only the Good Die Young” days prior while struggling for an explanation. Turner bows his head when it’s mentioned.

He looks at a world without this 17-year-old whose giant smile, outgoing personality, unwavering faith and unmistakable talent infected those he came in contact with.

Somehow, he gives voice to what hundreds of friends, family and fans, hundreds of those whose lives will never be the same, are left to ponder hollowly.

“I think that’s true, because he was too good,” he chokes out.

Silence.

Then: “I know that’s true. He was called, and he came.

“… But I wish he would’ve stayed.”

Man can’t control my destiny

November 11, 2010

0

Donate to The Battalion

$0

$5000

Contributed

Our Goal

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas A&M University - College Station. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs, in addition to paying freelance staffers for their work, travel costs for coverage and more!

More to Discover