The morning of the 1999 Aggie Bonfire Collapse was the day she grew up, said Sallie Porter, fall semester 1999 editor-in-chief of The Battalion. Porter, who is now a nurse anesthetist living in Asheville, N.C., said each November is, more than anything, a time of remembrance.

For 20-year-old Porter, it was a normal late night at The Battalion. She said the paper was put to bed around 1 a.m. — The Battalion’s deadline — and soon after, she left campus and drove home.

Porter arrived at her home at 1:45 a.m. and a little under an hour later she received a call from sports writer Doug Fuentes, Class of 2001, who had been outside the G. Rollie White Coliseum after work, waiting in line to pull tickets for the University of Texas game.

Fuentes, who was tossing a football with some friends, said he heard sirens but didn’t know what was going on.

“All of a sudden somebody was running by saying, ‘Anybody that knows CPR, or anything like that, get off to Stack site because Stack fell,’” Fuentes said. “So people just start running trying to get going. So that’s when I called Sallie and let her know what was happening.”

Porter, who lived about a mile from campus down from the Northgate area, immediately got into her car and sped back to campus.

“I got to do the one thing that people will never — or most people will never get to do — and that is to say, ‘Stop the presses,’” Porter said.

On-site Coverage

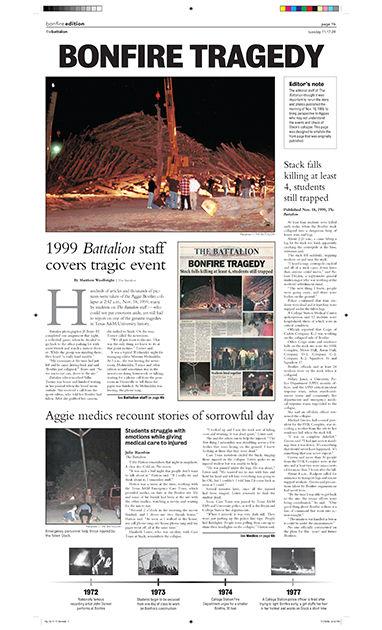

Porter said when she arrived on-site, no other media was present. What had been Bonfire looked like a “twisted mangled mess,” Porter said, and people didn’t know what to do. Prior to becoming editor, Porter said she had several roles at The Battalion, but photography was instinctual.

“So I just grabbed my camera,” Porter said. “The only thing I could think to do at that point in time was to take pictures.”

Being a student and Aggie first, Porter said the collapse was difficult to cover.

“I know for me that was the only thing I could think to do when it initially happened just because it was so heartbreaking to see — it was Bonfire. Bonfire was not supposed to fall,” Porter said. “And you see so much love and so much hours of labor put into it, and then to have it collapse — that for me initially was the way to reconcile that.”

Porter held a staff meeting with their adviser in the newsroom, which then was located in the Reed McDonald Building.

“I think for us, our focus, and what I emphasized in every staff meeting — and we had multiple staff meetings throughout the day — is that we will respect people on campus,” Porter said. “Especially with so many news media around, it was really hard for people. They were very frustrated with the fact that there were photographers there.”

Porter said she and student leaders met later that morning to discuss how they would approach the tragedy, specifically in regards to media coverage.

“And so we planned — where do we want the press, in what ways can we be respectful — because all of a sudden we had every national news organization in our backyard covering the story,” Porter said.

JP Beato, Class of 1996 and photographer for The Battalion, said he stayed on Bonfire site for two days continuously with staff “runners,” who would bring film when he ran out.

“I think I was just distracted because I had a job to do,” Beato said. “I think it’s easy to just distance yourself when you’re looking through a lens. You’re just documenting everything. I don’t think it really sunk in until after I went home the first time and took a shower. And then I realized that it was such a major thing that happened.”

Beato’s photo of student Timothy Doran Kerlee Jr. — one of the 12 Aggies who died in the collapse, who in the morning was still trapped under the Stack — was widely distributed across numerous publications.

Beato said the photo received some animosity, but that he was confident in its value in giving students a “human element” to what happened.

Kerlee was retrieved from Stack and taken to the hospital, where he later died of injuries. Beato said he and a group of other Battalion staff members went to the hospital to be amongst his family and friends.

“It was obviously emotional, but to kind of make a connection when you feel just like originally you were shooting from a distance, then you actually try to connect to the person in that photo,” Beato said.

In the newsroom

Guy Rogers, Class of 2002 and photo editor, said when the writers and editors arrived to the newsroom a few hours after Stack fell, they began to work on a new front page with whatever information they had.

“So then we just scrapped the whole front page and started laying out a new front page,” Rogers said. “We had to process film at that time. It was like 30-40 minutes to process film and scan stuff in, so we were rushing through all the stuff. I don’t even know if we put credits on the photographers’ names.”

Fuentes stayed in the office assisting in what was needed and relaying information to other media organizations.

Like many students, Fuentes had a test later that morning, but didn’t go. He said he didn’t go to sleep until around 10 p.m. the next night.

“I didn’t realize out of the newsroom how long we had all been up; it was kind of all a blur,” Fuentes said. “But we had to get that story out, we had to get that information, so I hadn’t really thought about [going home]”.

Publishing the first story

The Battalion staff worked fervently to get a new issue out. Around 2:30 p.m., the first Bonfire issue was delivered to campus.

Because not everyone was accustomed to the Internet in 1999, publishing a print issue the day of the tragedy was an accomplishment, said Will Hurd, 1999 A&M student body president and congressman elect for the 23rd district of Texas.

“It was a place where everyone could try to go to get some answers,” Hurd said. “And most people probably got the most accurate understanding of what was happening from reading The Battalion that day.”

Fuentes said the content published in Bonfire articles was of a sensitive nature, but it was a story that needed to be told.

“One of the reasons I got into journalism is because I loved sports,” Fuentes said. “So that was a big draw for me, but at that time, I felt like I was a sports guy who did newspapers. And then after that day, it kind of switched — I was a newspaper guy who just happened to do sports. I kind of felt like I got it, I felt like I got the whole thing. I saw what we could do and what we can do for people.”

Porter said being able to watch the staff grow and develop as journalists with so much respect for other students was something wonderful that emerged from a tragic situation.

“I felt like we told the story with so much respect and so much love,” Porter said. “That was the positive thing that came out of it — that no national media could provide that kind of coverage. We told the story, and that was something that was really neat and really wonderful — that if anything good that came out of that time, was that students told the story of students.”

Photos taken by Battalion photographers in the days after Stack fell.

File photo.

Stop the presses’: The Battalion covers the collapse

November 16, 2014

0

Donate to The Battalion

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas A&M University - College Station. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

More to Discover