As the Iraq army, disillusioned by a lack of military experience, loses city after city to Sunni militant groups, the threat of losing the key city of Baghdad gets closer.

Andrew Natsios, director of the Scowcroft Institute of International Affairs, former administrator for USAID and former manager of reconstruction programs in Iraq, said that if the Iraqi Government collapses at the hands of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, a dangerous chain reaction will in turn threaten U.S. interests.

“If the Iraqi government collapses and the ISIS takes control of Iraq, we will have basically a Bin-Laden-like political movement running a country — a whole country that has oil, that has a lot of weaponry that we equipped the Iraqi government with and would be extremely hostile to the United States,” Natsios said. “And there would be a civil war, because the Shiite are not going to let this happen. It would cause more chaos than what’s happening in Syria. You see what’s happening in Syria? Triple it in Iraq. Then, you’d have Iran invade, because Iran does not want to have a radical Sunni state on its border.”

Natsios said that the two principles of religious tradition in Iraq, Sunni and Shiite, are central to the conflict. Resentful of the poor treatment from Shiite government in Iraq, headed by Prime minister Nouri al-Maliki, ISIS forces began taking control of principally Sunni areas in the North that are alienated from the Maliki government in Baghdad.

A third player, the Kurds, who created their own independent state without formally seceding from Iraq, have also been overrun by the ISIS in areas, Natsios said.

Natsios said ISIS forces’ ability to take control of areas of Iraq so quickly in a matter of days came as a surprise to the U.S.

“The Iraqi army just melted away,” Natsios said. “I think United States Intelligence and the Pentagon and the White House were shocked at how fast the army collapsed.”

Richard MacNamee, professor of international affairs specializing in government intelligence operations, terrorism and counterinsurgency at the Bush School of Government and Public Service, said the recent invasions have been a long time coming for those studying the area.

MacNamee said the ISIS’s ability to take control is not solely linked to the weakness of the Iraqi army the U.S. helped rebuild.

“There’s a lot of moving parts, but this should come as no surprise,” MacNamee said. “A lot of us knew that when they decided to go and push, it wasn’t so much a case of how weak the Iraqi army that we had built was going to be, it was the fact that they had already managed to recruit most of the Sunni tribes that were in Iraq.”

This alignment of forces is not ideologically bound, MacNamee said. Whereas the ISIS want the establishment of a caliphate and an Islamic state, the Sunni tribes that assist them don’t necessarily want the an Islamic state. They want a more effective government that is not as Shiite leaning as they believe the Maliki Government to be.

Unlike the Iraq army which lacked motivation to fight in hostile Sunni areas, Natsios said ISIS is heavily motivated to reestablish Shariah law, making the prospect of negotiation with the ISIS bleak.

”You don’t talk to the ISIS,” Natsios said. “They don’t negotiate under any circumstances, they just don’t. They want to re-establish the Caliphate, which fell in the early 1920s when King Abdülmecid collapsed the Ottoman Empire and created a Turkish state that was secular.”

As debate ensues to whether or not this current situation is the result of the U.S. withdrawal from Iraq, MacNamee said the decision to withdraw troops was made at a time when Americans felt the Iraqi forces had met standards of self-sufficiency. But now, onlookers are finding that these standards were never met.

Natsios said the decision to withdraw troops was disastrous and the U.S. should have kept 10 to 15 thousand troops in Iraqi bases. Natsios said such a move wouldn’t prompt casualties, but would allow the U.S. to send the signal of stability by implying that it is ready to intervene if necessary.

“We’ve kept troops in Kuwait since the Iraq war in 1991, there’s a permanent base there,” Natsios said. “We could have easily had a permanent base in Iraq to further assist the Iraqi army with training. We’ve had bases in South Korea since the Korean war, we’ve had bases in Europe throughout the entire cold war.”

Natsios said that in many cases these countries pay for the U.S. presence, as is the case with many NATO bases in Europe and with the U.S. bases in Kuwait.

Joseph Cerami, senior lecturer and director of the public leadership program at the Bush School of Government and Public Service, said there is no solution that will eliminate the threat posed in the Middle East completely, but that the American public has to encourage the White House, State Department and Pentagon to work together to bring about a diplomatic solution to these long standing problems.

“We are going to have to work with Allies,” Cerami said. “We are going to have to negotiate with people we don’t necessarily agree with, like Iran, with countries that we don’t share the same values with like Saudi Arabia in some cases, and with weak nation states like Lebanon to try to put the pieces of the puzzle back together. We won’t eliminate this threat, but need to be able to figure out how to manage it so that we can provide for our continued security and safety.”

For MacNamee, even the expression “War on Terror” is misleading, he said, because “war” implies there is an a finite end with generals signing papers. MacNamee said the threat of terrorism has been around forever and will continue to exist.

“To call it a war on terrorism is incorrect because wars have ends, and this will never end,” MacNamee said.

Bush School professors discuss ISIS

June 15, 2014

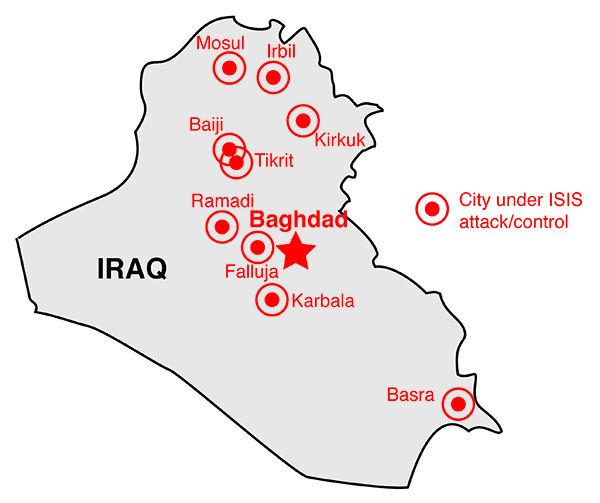

The areas marked in red are under attack or are already controlled by ISIS. Graphic by Josh Seal

0

Donate to The Battalion

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas A&M University - College Station. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

More to Discover