A resident of Bryan-College Station for over seven years, Tay Huggins recalled her first true encounters with the community’s punk rock scene at the Revolution Cafe and Bar, or “Revs,” in Bryan.

A musician herself, Huggins said she went after hearing about an open mic at Revs and, after some time, was introduced to a man named Colton French, a singer-songwriter from the Brazos Valley. From there, under the orange and red hue of Revs’ lights and likely yelling over the reverberations of an amp off the walls, she was introduced to a band called Wisdom Cap, and its members brought her fully into the scene as both audience and an artist.

Only hearing Northgate bands from her first years living in town, Revolution’s live music opened a whole other world.

“Obviously, there’s music all over [Bryan-College Station], but the Downtown Bryan punk rock scene was just so rich and so beautiful,” Huggins said. “And because we’re a college town, we have a mix of just so many people, and with that you have so many different genres. So, you may go listen to a country band one day and an indie rock band the other day and then walk into a bar and there’s someone playing a banjo the next day and spoken word the next day.”

The plethora of people and diversity in tastes drew Huggins in, she said, even finding “weird hybrids” of music genres and art broadening her own work. Speaking to other musicians, Huggins learned a School of Rock was opening in the area. Now, she works there as a social media manager and teaching as a vocal instructor and assistant band director, herself aiding the cultivation of the Brazos Valley’s arts. The scene is not what it once was, however.

Huggins’ time in Brazos Valley’s creative communities has seen many places, artists and their art come and go; Revolution and her own project — Well Hung Art Gallery, which opened and closed in 2021 — included. While Colton French is still based in Brazos Valley, many of the artists that brought her onto the scene have themselves moved on.

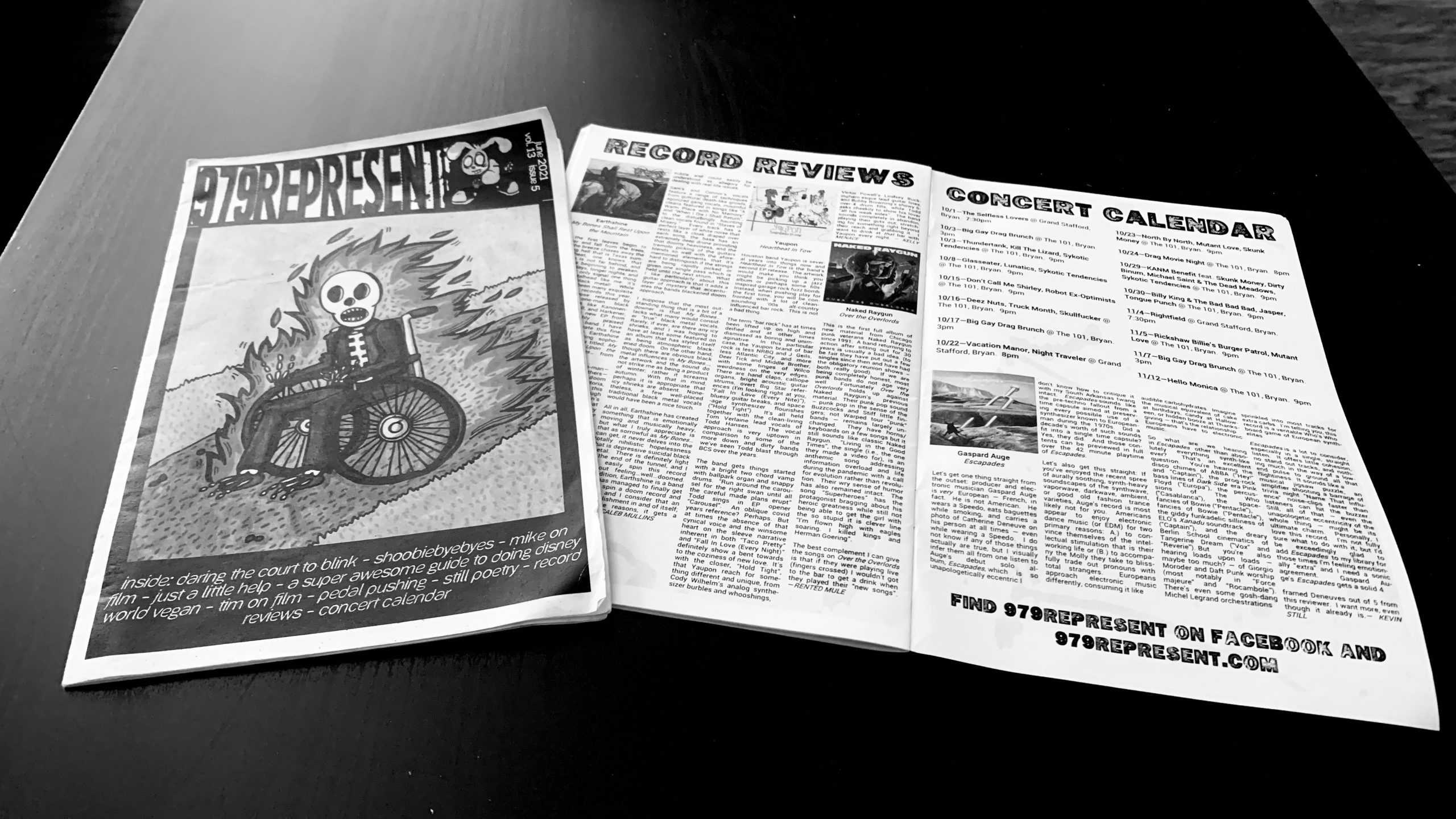

One project of some local creators not only documented but arguably defined the alternative scene itself. Written and illustrated by locals about Bryan-College Station events, a ‘zine called 979represent can be credited for promoting and connecting the artists Huggins came to know. Running from 2009 to December 2021, the black-and-white, xerox pages of the zine entitled itself “the local magazine for the discerning dirtbag.”

“They would always promote local artists and where they were playing, or local artists and what they painted. The covers of the designs were always local artists, for instance,” Huggins said. “And, they wrote everything from comedians in town to musicians in town to painters in town and everything in between. We even have a lady who makes pickles, and that’s an art form in its own right.”

Two years before Johnny “Football” Manziel made his debut and sparked a renewed interest in this area, 979represent’s editor Kelly Minnis was already documenting the start of the area’s “boomtown” development in the 2010s. Amid the growth, Minnis and his fellow contributors not only witnessed, but directly spurred on a blossoming arts and the music scene in the Brazos Valley. It was their passion project.

Kelly “Menace” — as the ‘zine came to refer to him — moved to College Station in the summer of 2006, working, creating and performing until moving to North Carolina in fall 2018. Running a magazine for locals while no longer being one yourself was a driving force behind discontinuing the ‘zine last year, once enough writers and editors had all similarly moved on, Minnis said.

In 2007, Minnis had already been in College Station for about a year. He’d met Michael Scarborough and Matt and Niki Shea, his eventual partners in 979represent, playing in a smattering of bands and even running a music festival together. But before any of that, they were bored.

“Pretty much, the four of us were bored and decided to do things so we wouldn’t be bored,” Minnis said.

“There were a lot of people that were past college age but weren’t quite ready to kind of stop being creative. So we just started doing things, you know, throwing out ideas. ‘Wouldn’t it be great if we ran a record label?’ Well, sure. Let’s just do it. ‘Well, we can just do it?’ Sure, we can just do it, who’s going to tell us no? ‘Let’s start a newspaper.’ We had all these sorts of ideas and decided to take them from just talking about it to doing it.”

The group started a record label, Sinkhole Texas, Inc., joined and started bands such as The Ex-Optimists and generally began building a community.

“The great thing about Bryan-College Station at that time, and actually still to this day, is that there aren’t a lot of boundaries and gatekeepers for doing things as there are in towns where there are more established scenes, like Austin or Nashville or Seattle or wherever,” Minnis said. “We could pretty much do whatever we wanted and found that we had a lot of like-minded people who either were involved with the university or had dropped out or had graduated and stayed in the community.”

Facebook was a newborn baby in terms of social media platforms, so at the time, the group and related friends and collaborators were still on MySpace and web blogs, Minnis said. He and Matt often had time on their hands, sharing videos and music back and forth, inevitably wanting a central place to put all they found. The idea came to publish a compilation of local hip-hop artists through Sinkhole, but Minnis said in between coming up with the idea and actually compiling, most of the artists had moved to Houston or Dallas. Left with a name and nothing to tie it to, 979represent began as a web blog.

“The Eagle used to have a section of the newspaper called ‘The Spotlight,’” Minnis said. “It was a Thursday, weekly tabloid-style newspaper that they would include with the Thursday issue, and then they also put it around town in a bunch of different places. It was meant as an entertainment pullout — as a competitor to the Maroon Weekly — where they interviewed musicians. They had movie reviews, they had book reviews, they had entertainment stories and they had a calendar for events that were happening in the Brazos Valley.”

Right around the ‘zine’s birth, the final editor for The Spotlight reached out to Minnis, keying him in that The Eagle was “blowing it up.”

“I was like, ‘Oh, well, crap. There’s a gigantic hole now that The Spotlight used to at least kind of halfway cover. And nobody’s doing anything like that here.’ And so I thought, ‘I wonder if we could put out our own Spotlight and take 979represent off of the internet and put it into print.’”

Minnis and his friends had some background in publishing — school newspaper experience, writing record reviews for different magazines and blogs, etc. — the main hurdle was getting it printed. It seemed “nonsense” to restart an early 1990s form of print right as social media was kicking off, but Minnis, and later contributors, couldn’t shake a deep love for the physical media.

“I teach English at Blinn [College], so I love words. I love language,” Kevin Still, a later writer for 979represent, said. “And like Kelly, we are both big fans of physical media. We are record collectors; we try to stay away from CDs, but you kind of can’t help it; we’ve got far more CDs than we can deal with. We’re both big book collectors and stuff like that, so this ‘zine was truly our way of bringing that love of physical media out.”

For Still, Minnis and surely many of 979’s writers and artists, writing the ‘zine was a means to put concrete and abstract ideas and emotions alike into a tangible product, something that can be handed to somebody who has to choose to engage with it.

“We’re leaving behind records of our interactions with media and with each other and with the moment, with a scene that was really unique at a particular time,” Still said.

Still said he isn’t a musician, not even a physical or digital artist, so upon meeting Minnis and having a shot to write in a printed public forum, he jumped on it.

“979represent is a local magazine for locals with no hopes of ever turning a profit,” Vol. 1, Issue 1 of the magazine reads.

The cover of Vol. 1, Issue 1, published December 2009, features the architectural mock-up sketch of what became the G. Hysmith Skatepark in College Station off Rock Prairie Road. It was the first issue to divert from costly newsprint produced in conjunction with The Eagle, instead printed during break-hours and after-hours at the A&M math department, where Minnis worked.

“Part of being editor with Kelly was I would meet him on a Friday morning, he would hand me a box — literally a box of just collated paper — and I would take them and physically fold and staple them. And then I would drive them around and drop them off at Arsenal Tattoo, [The Grand Stafford Theater], The Village Cafe and Curious Collections when it was up and running. Obviously, Revs was a huge place that we put the majority of them.”

The worst thing about publishing 979, Minnis said, was paying for it. But with the xerox format, advertising became far less of a focus than original content. Minnis said he felt magazines like the Maroon Weekly were just a means for local businesses to advertise to students; 979 wanted to focus away from Northgate, from campus, and more on the arts of Bryan.

“There used to be a place for bands to play on West Gate,” Minnis said. “Around the corner from you know, on Wellborn Road there from University. The Ramones played at the Tap in the ‘80s, Nirvana played at Dinosaur Jr. and Green Day, No Doubt, played at the Stafford back in the ‘90s. There were things going on then, but coming into the 2000s that stuff was all kind of done and over with.”

“What I was most passionate about was that, at the same time that 979 was starting to develop, we were also developing the music scene in Bryan-College Station. And we would play shows with bands from all over the country and think, ‘Wow, these guys are great! Somebody should write something about them,’” Minnis said. “‘Yeah, oh, gee, we got a paper; why don’t we write about them?’

“So, we would write record reviews, or I started writing reviews about a piece of guitar technology — a new synthesizer or something — I guess where my focus was, and continuing to have a place for a concert calendar. So, anybody could pick up the paper and go, ‘OK, this is the stuff that’s going on around here.’”

Shows were hit-or-miss around town for The Ex-Optimists and other bands before Rola Cerone, who opened Revolution in 2003, opened up to having “louder” bands play at the bar.

“There was just a really beautiful thing happening in Downtown Bryan at Revolution,” Still said. “Sometimes you’d have a couple people who were in three or four different bands. Just kind of exploring different sounds, ‘And this is my punk band, and this is my heavy metal band, and this is my new wave band.’”

As the scene picked up, a camaraderie began to form among the mix of Brazos, Austin and Houston artists. Bands would come in from the other cities, often bringing their friends to play, and 979 members, including the Sheas, would make sure the artists had a place to stay and eat, Minnis said.

“I remember going to some of these shows where you would see a band play a set, and then they would haul ass to just rip their stuff down and get in the car, or in the van, so they could run back in and be on the front row of the next set that was about to play,” Still said. “These were bands who loved playing music, they loved playing together and seeing each other wearing each other’s T-shirts; just no competition, just pure brotherhood of music, and it was a real sweet spot.”

This camaraderie was the perfect storm to give way to “LOUD!FEST,” which ran until 2018 and put Bryan-College Station on the map as a bridge between the Austin and Houston scenes. Still became a kind of roadie for The Ex-Optimists and the other bands his friends played in during that period.

“One of the things I loved about this was being with my friends who are in the bands, getting to Houston and, ‘Here’s this little band from Bryan-College Station,’” Still recalled about traveling with them some years after 979 and LOUD!FEST had begun. “There [were] so many people who are crazy excited to see them in there, but then I find out they’re all Houston musicians. We get there and all these musicians are coming out to see Kelly [Minnis] and Michael [Scarborough] … play because these are the people who are uniting us. These are the people who are creating a scene for us. I loved showing up and seeing my friends, so honored.”

Pages and pages have been written by 979’s writers over the years about LOUD!FEST, one of the most memorable to Still being “Drunk Detective Starkness’ guide to LOUD!FEST,” a primer in all the do’s and don’ts of concert etiquette — drinking heavily was encouraged.

“Alright you f***ing rubes, Drunk Detective Starkness has made it through a few years of LOUD!FEST now, and let’s level with one another. Does he remember everything? Of course not. Is this a definitive guide on things to do and things not to do? Of course not, but it comes from a good place,” contributor Jeremy Stark wrote.

Still and Minnis said Stark went on to help found The 101 bar and concert venue, Revs’ spiritual successor since closing in 2020 due to COVID-19, still yet to reopen.

Minnis said the lack of an “old guard” is what really motivated him and the broader community to begin making art in Bryan-College Station.

“There wasn’t any sort of gatekeeper telling us that we could or couldn’t do something. But, in a way, we had become that establishment. I only one time ever turned anybody away from doing something with us. But, at the same time, it always seemed odd to me that we were doing things for Gen-Xers or maybe older millennials,” Minnis said.

“And at some point, I just kind of felt like there was going to come a time when somebody 20 years old would look at a bunch of us, fat and graying, doing this stuff and be like, ‘This doesn’t say anything to me, this doesn’t represent me, this doesn’t say anything about what I’m going through.’ In a way, I do hope that with us kind of stopping to do things, that spirit of ‘anybody can do something there’ — it still exists.”

As Still put it, life began to happen to those who made up the core of the scene. As people parted and went on to other things, so did the camaraderie and ‘brotherhood of music’ that existed at the time. The amount of shows began to decline, and even though the artists rarely worked for the money itself, the wave of pandemic shutdowns was the final nail in the coffin.

“I do really hope that other people who wind up there after graduation, you know, the 20-somethings, are like, ‘Well, shit. There’s nothing to do here. How do you make something happen here? I don’t know, let’s go talk to Jeremy and see if we can use his bar for something.’ Or, ‘Oh, wow, that 979represent thing. Remember that? Man, we could do our own version of that.’”

With so many artists spread across the country, Minnis and the former 979 contributors and artists are taking time to regroup, he said, to hopefully launch a new publication called “Dirtbag Quarterly.” Creating the same open forum, but on a national scale for all the underrepresented scenes and “discerning dirtbags” across the U.S.

Huggins said she misses the folks who have moved on and what made the 2010s scene special, but she isn’t without hope. Nor is the area lacking artists, she said.

“It was very disheartening initially, but I’ve learned to adjust with College Station is, you know, this is not a settle-down town, unless you’re a little bit older, or a professor, you know, things of that nature,” Huggins said.

“That’s just kind of the nature of things here; somebody might start a paper or start a business or start something really cool in the hopes that someone will continue it when they leave, but typically that doesn’t seem to happen. It kind of falls through, but that’s OK because something new always occurs, which is fun, too. Because once one thing fizzles out, you find something new.”

Bryan-College Station has so much potential to be a beautiful, vibrant place, Huggins said. Marketing is one tool for that, having figures such as KBTX’s Rusty Surette to be a face for the community. Yet, the community also needs more students to take part in the creative worlds beyond campus, Huggins said.

“More people need to be out there like, ‘Hey, Downtown Bryan, come to the Big Gay Brunch, come to The Village and get a cup of coffee and see the cool artwork of one of the local artists. Go to Savage Diva where it’s all local, these are cool places that you guys are missing out on because you’re staying in College Station and you’re going to, what, Grand Station Entertainment?’” Huggins said.

Neither Minnis, Still, nor any of the 979 artists have a monopoly on creative ventures, Minnis said. It wasn’t even his idea to use the xerox format; 979represent followed in a long tradition of artists before them, and there’s still plenty of room. There were times when the ‘zine would be pushing a deadline and Minnis said he had to write to fill holes, scrawling out a political column at midnight. But, for the most part, as long as the creator has people that will help them do it, it’s really not that hard, Minnis said.

“There was a previous scene there in the ‘80s and a previous scene there in the ‘90s,” Minnis said. “These things kind of ebb and flow; there’s a crest, and then the tide goes back out. So, this is one of those times when the tide is back out. And it’s time for other people who are there to kind of pick it up.

“And hopefully there’ll be more people like us that are bored and will look around and say, ‘Well, there’s nothing to do around here. OK, am I a passive observer of culture? Or am I going to actually pick up something and be a part of the culture?’ Hopefully, they’ll have that drive to do that and there’ll be another thing that happens in [Bryan-College Station].

“I do hope in a way that we’ve erased the blackboard on what we’ve done in [Bryan-College Station], and it’s kind of absolutely free again, for people to do what they want to do.”