A new Texas A&M research group is drawing inspiration from the human brain to rethink the computer.

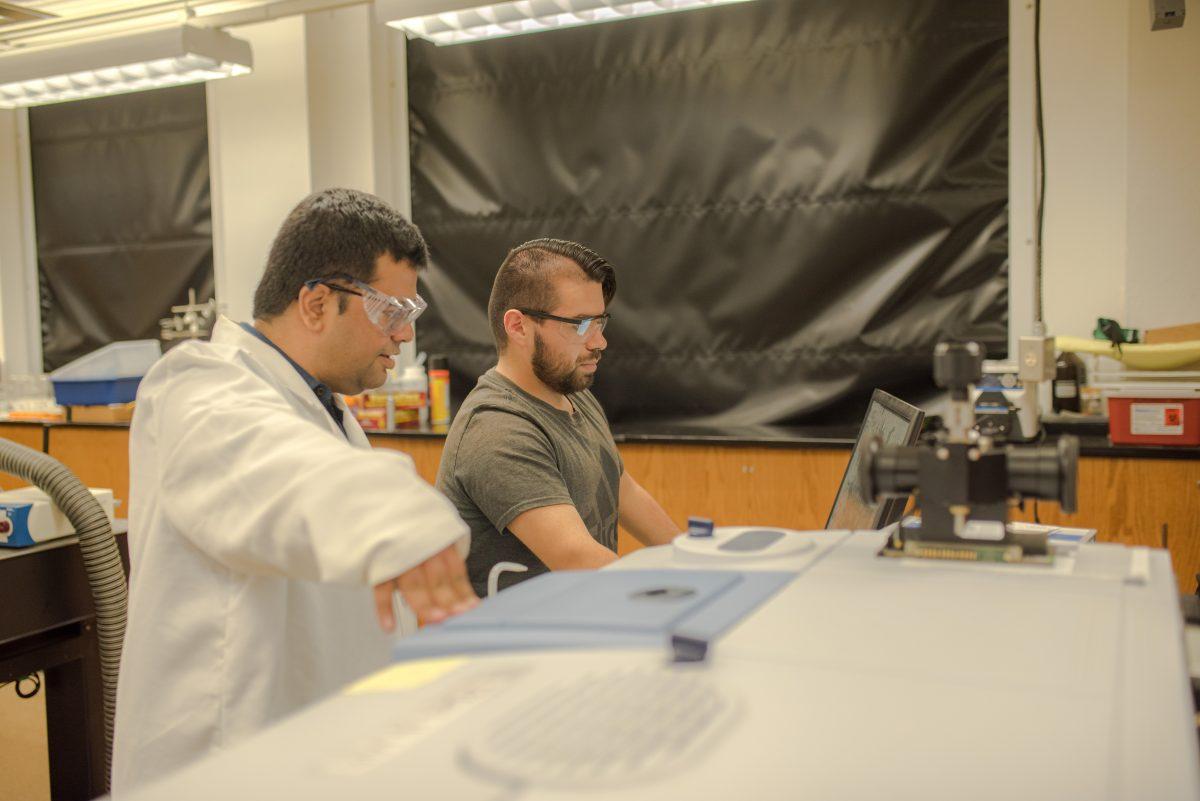

Sarbajit Banerjee, Ph.D., professor of chemistry, materials science and engineering, and R. Stanley Williams, Ph.D., professor of electrical and computer engineering, are leading a new U.S. Department of Energy-funded Energy Frontier Research Center, or EFRC, the first led by A&M in the program’s 13-year history. The group, focusing on Reconfigurable Electronic Materials Inspired by Nonlinear Neuron Dynamics, or REMIND, will investigate ways to build computers that mimic the human brain in order to process information rapidly and efficiently.

In 2022, the energy that computers demand is growing fast. This demand necessitates advances in the energy efficiency and thus the processing power of computers, but today, increasing the processing power of computers has become more difficult than ever.

According to Matt Pharr, Ph.D., a professor of mechanical engineering and another member of the EFRC, advances in computer performance are driven by increasing the physical performance of the most basic building blocks of computers — silicon chips. Pharr said that while the power of traditional computers has increased quickly, this growth may soon hit a wall, after a mechanical limit to their effectiveness is reached.

“Since the information age has started, computing capacity has doubled every 18 months or couple of years or so,” Pharr said. “So it’s very good and extremely impressive, but we’re approaching fundamental limits when that rate that we’ve been seeing is going to completely slow down and start to plateau out.”

With humanity pushing the traditional silicon transistor to its physical limits, Banerjee said he and his team have looked toward another way to improve the ability of computer systems: fundamentally rethinking the architecture of a computer. In order to figure out how to improve the man-made computer, Banerjee said he draws inspiration from nature’s best computer: the human brain.

He likes to demonstrate the power of the brain by asking people to identify a picture of a Labrador. Almost everyone instantly knows it’s a dog, and some even know the breed. Banerjee said that our ability to instantly determine what we are looking at showcases the impressive efficiency of the brain.

“That is your brain working on 20 watts,” Banerjee said. “Try asking a computer that question. It’s gonna take about a million times more energy because it’s going to have to compare this to all sorts of pictures that it’s ever seen. Is it a building? Is it a car? Is it a toy? Is it a dog?”

Banerjee said while the modern computer excels at completing tasks for which instructions are already provided, such as solving equations, it is vastly inferior to the brain for novel tasks such as recognizing a dog that we’ve never seen before. Unlike computers with their linear architecture, the interwoven structure of the brain’s neurons allows one to “think” and forge new connections between different areas of our consciousness.

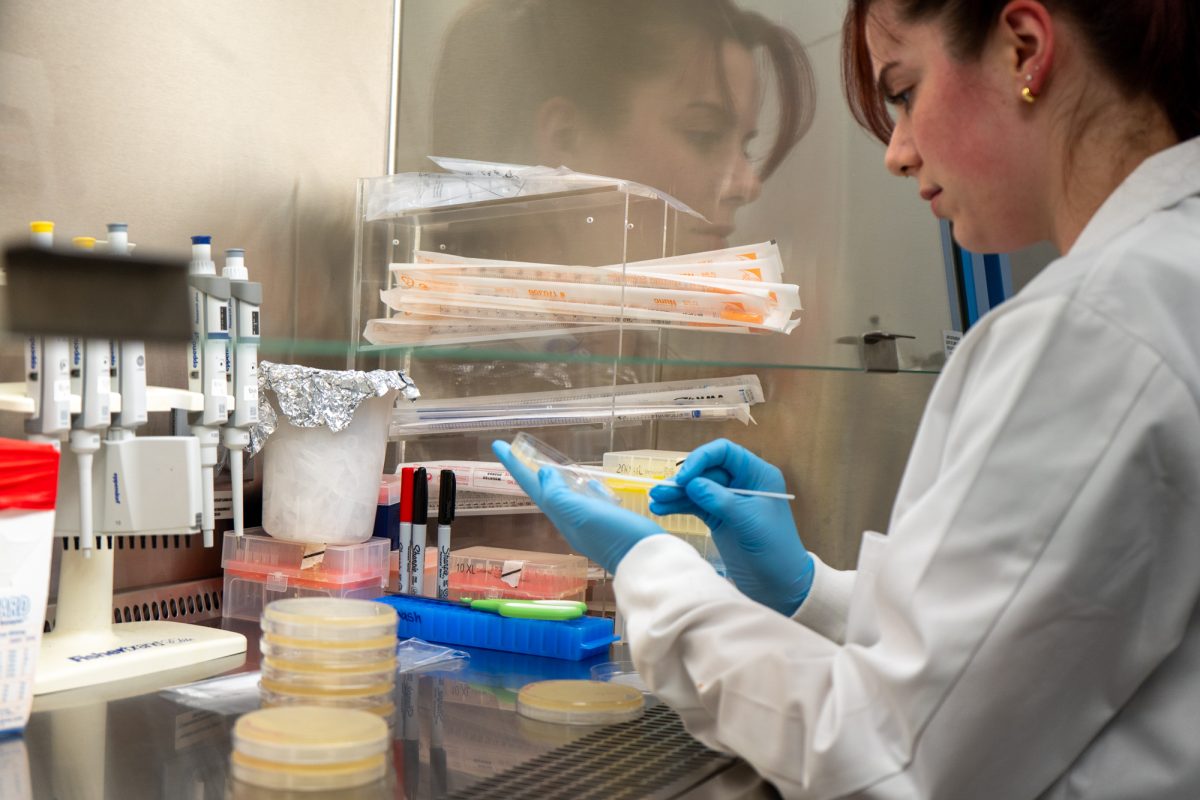

In order to mimic something as complex as the human brain, the EFRC team goes back to the basics: exploring the chemistry and materials of computing components. Marcetta Darensbourg, Ph.D., a distinguished professor of chemistry and a member of the EFRC team, said that while the researchers can’t precisely replicate the human brain, they hope to synthesize materials that can emulate its function.

“I have to admit, no chemist has ever matched nature,” Darensbourg said. “But we do our best to emulate it.”

One material of particular interest to the researchers is vanadium dioxide, a chemical with the unusual property of producing pulses of electric currents when heated. Banerjee said this property is strikingly similar to how brain cells fire pulses of electric current to convey information. Banerjee’s team found that after tweaking the vanadium dioxide by adding boron to the mix, the combined material even stores information on the time it took to cool down after a pulse, mimicking how brain cells remember the electrical signals that passed through them.

Banerjee said that, in the future, a network of vanadium dioxide cells can be connected to each other to form a computer that is not only more energy efficient but truly thinks and learns like a human, similar to artifical intelligence, or AI.

“One of our goals is to come up with hardware that is purpose-designed for AI rather than imposing AI on traditional circuitry using algorithms,” Banerjee said. “We’re looking for computers that, much like the human brain, are able to perceive things in three dimensions, respond, learn and really encode intelligence, not just arithmetic.”

Williams said at the EFRC, fundamental science and cutting-edge engineering converge to take on an incredible challenge, all within the Texas A&M system.

“Most of the large multidisciplinary center efforts like our EFRC usually involve faculty members from many different universities to be able to cover the diverse topics with highly qualified personnel,” Williams said. “For [A&M’s EFRC], all of the academic researchers are faculty at TAMU, which demonstrates the breadth and depth of the scientific and engineering talent that we have.”

Banerjee said this new lab will enable A&M to become a hotspot for the development of both the physical construction and the minds of AI systems.

“The Texas A&M system is very well placed to tackle this because we have the broad range of expertise needed to go from foundational science all the way to technology,” Banerjee said. “Bridging across chemistry and material science and many other engineering disciplines is needed to really tackle a problem of this magnitude. You can’t do this alone. We’re looking forward to Aggieland becoming an epicenter for the design of both the software and hardware sides of AI.”