The early 2000s now feel like a fever dream. Though “Bush v. Gore” presaged the more partisan politics that accompanied social progress, fourth-wave feminism, with its focus on intersectionality and internet activism, had not yet taken root. Heroin chic was all the rage. Men who bathed and groomed themselves regularly were called “metrosexual” to distinguish them from full-throttle homosexuals — all the while, gay marriage received support from neither political party.

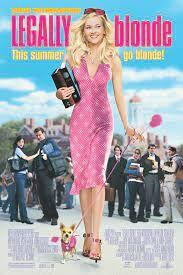

#MeToo had not yet become a rallying cry, a reckoning yet to come. Onscreen, rom-coms thrived, and these usually starred a skinny, blonde girl pursued by a tall, dark, handsome and usually caucasian man. “Legally Blonde” was revolutionary because it turned this idea right on its head by portraying the woman in pursuit instead.

Years before “White Lotus” reintroduced us to Jennifer Coolidge, parodying the idle rich as Tanya McQuoid, she played Paulette, a lovelorn manicurist, in Reese Witherspoon’s star-making vehicle “Legally Blonde.”

“Law school is for boring, ugly, serious people,” Elle Woods’s dad warns us in “Legally Blonde,” a film that has done much to dispel this preconception of legal education.

For the uninitiated, “Legally Blonde” centers on Elle Woods, a sorority president from Southern California who decides to follow her ex-boyfriend to law school at Harvard University in Boston, Massachusetts, to win his love back. But if the premise sounds dubious, as you will soon see, the film passes the Bechdel Test.

Directed by Robert Luketic in his feature-length debut, it is a lesser-known fact that “Legally Blonde” began as a novel conceived by Amanda Brown. Despite being the sole author listed, according to the U.S. Copyright Office, Brown shares the copyright with Brigid Kerrigan, a childhood friend and controversial figure.

Kerrigan first made headlines for hanging a Confederate flag outside her dorm window at Harvard. Due to a non-disclosure agreement, Brown has not said much about Kerrigan’s involvement in the novel, but Kerrigan did confirm her involvement around the release of the film in 2001.

Elle broke barriers upon the film’s release. She was a bimbo with a brain, a seemingly novel idea at the time. She goes to law school for love and graduates as valedictorian, a girlboss blueprint if there ever was one. Elle’s turn from aspiring towards marriage into aspiring towards a career mirrored the cultural expectations now placed on American women, who were told they can and should aspire to have it all: relationship and career, beauty and brains. In pursuit of her own fulfillment beyond romance, love ends up falling into her lap.

Elle undergoes de-bimbofication in pursuit of credibility, trading her colorful ensemble for a drab business professional suit after winning a coveted internship only to reverse course near the film’s end. This happens when the professor Elle is working under hits on her, which she rebuffs and gets blamed for. She plans to leave Harvard and go back to California, back to where she “makes sense,” until a female professor gives her a pep talk. Accordingly, in the next scene, Elle triumphantly returns to the court clad in a hot pink skirt suit.

After a rocky start cross-examining Chutney, whose father Brooke Windham, on trial, allegedly shot, Elle senses something isn’t right with her alibi about being in the shower during the crime’s commission. Chutney mentions having gotten a perm earlier that day and Elle’s wheels start turning.

The cardinal rule of perm maintenance, after all, is to avoid moisture for 48 hours at the risk of deactivating the perm’s ammonium thioglycolate. Chutney’s perm was still intact, undermining her testimony and compelling her confession. Elle’s supposed liability — her femininity — becomes her best asset.

“The rules of hair care are simple and finite,” Elle says to a reporter after the judge dismisses the State’s case against Brooke Windham. “Any Cosmo girl would’ve known.”

This film accomplishes a herculean task in making us sympathize with a rich, blonde bimbo by placing her in a fish-out-of-water situation. Away from the low-brow West Coast, where Elle’s money, charm and beauty hold more sway, she must now prove her ability to the New England elite. When looked at through this lens, the movie becomes about the new money underdog vs. the old money establishment. Elle, after all, is not destitute.

Elle does not pull herself up by her own bootstraps, contrary to what our politicians would have us believe; she relies on her community and her not-insignificant privileges in order to emerge victorious. But reading into this might seem futile because “Legally Blonde” doesn’t attempt to impart a revolutionary message beyond female empowerment. It is a feel-good movie, replete with a bankable star, not “Casablanca.”

Let us not forget “Casablanca” was just another film churned out by the studio system, which throughout the years, has risen above the fray. Similarly, Shakespeare was once considered low-brow. But times change. It is debatable whether “Legally Blonde” is now part of the American film canon, but the thousands of aspiring law students who apply for admissions each year have undoubtedly heard of, if not watched, the film.

Since 2001, no other film about law school has had such an outsize cultural impact. Elle Woods has become a symbol, but what exactly does that symbol represent? Despite being a foundational bimbo, in the context of 2023, Elle Woods is the quintessential aspirational girlboss, the intersection of idealized femininity and materialism made manifest.

In a post-#MeToo, post “Roe v. Wade” world that has grown past #Girlboss feminism, is Elle Woods still the heroine we want her to be? It’s quite jarring to think that Elle Woods enjoyed more reproductive autonomy in 2001 than incoming female law students in 2023. Witherspoon, who is set not only to star but produce the third installment of the “Legally Blonde” trilogy, will soon have to reckon with the cultural shifts since her star-defining turn over two decades ago.