Preheat the oven to 325 degrees Fahrenheit, bake for 20 minutes and cool for another five minutes — even the most simple of tasks in cooking have millions of chemical reactions happening on the surface level. On Friday evening, a Harvard physics professor taught the audience how to cook from a physics standpoint.

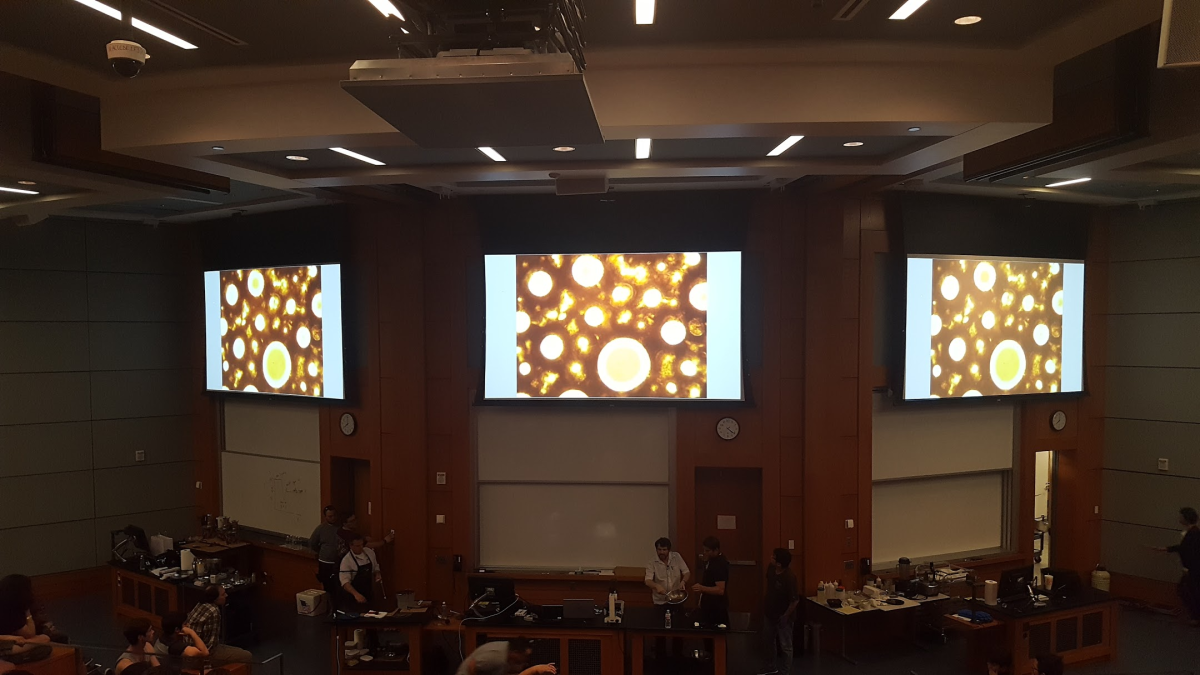

Kicking off the Physics and Engineering Festival, Harvard physics professor David Weitz and local chefs Peter Madden of Mad Taco and chocolatier Mitch Siegert from the popular Truman Chocolates teamed up to explore the physics of cooking. Presenting at the Mitchell Physics Institute building, they explained the physics behind chemical reactions when cooking and how common food items are prepared — everything from perfectly poached eggs to the foamy whipped cream.

While teaching physics at Harvard, Weitz said his wildly popular physics-of-cooking class is aimed at non-science majors, and he was motivated to use innovative methods to teach physics.

“I wanted to find a way to teach physics where people would like it,” Weitz said. “I teach the physics of cooking and people like it — now people line up to take the course. I want people not to be afraid of science, I want people to enjoy science.”

Weitz said a lecture of celebrity chef Ferran Adria at Harvard inspired him to start a collaborative course with fellow mathematician Michael Brenner and invite chefs as part of the course. He described the eclectic combination of a science lab and a kitchen — and the use of molten chocolate cakes to understand thermal transport.

“We had a recipe of the week, this is one of the signature recipes, molten chocolate cake,” Weitz said. “This is a great way to measure how rapidly how heat comes from the outside, it diffuses in, we talk about diffusion equation using the cake. You cook it for different amount of times and measure how much is molten inside.”

There’s a science behind everything, and understanding why and how physics affects cooking can help efficiency. Seigert said participating in these exercises reveals new culinary methods and recipes by understanding the simple physics behind many of the techniques used by chefs.

“You can eliminate a lot of the trial and error and branch out from there and become more successful,” Seigert said.

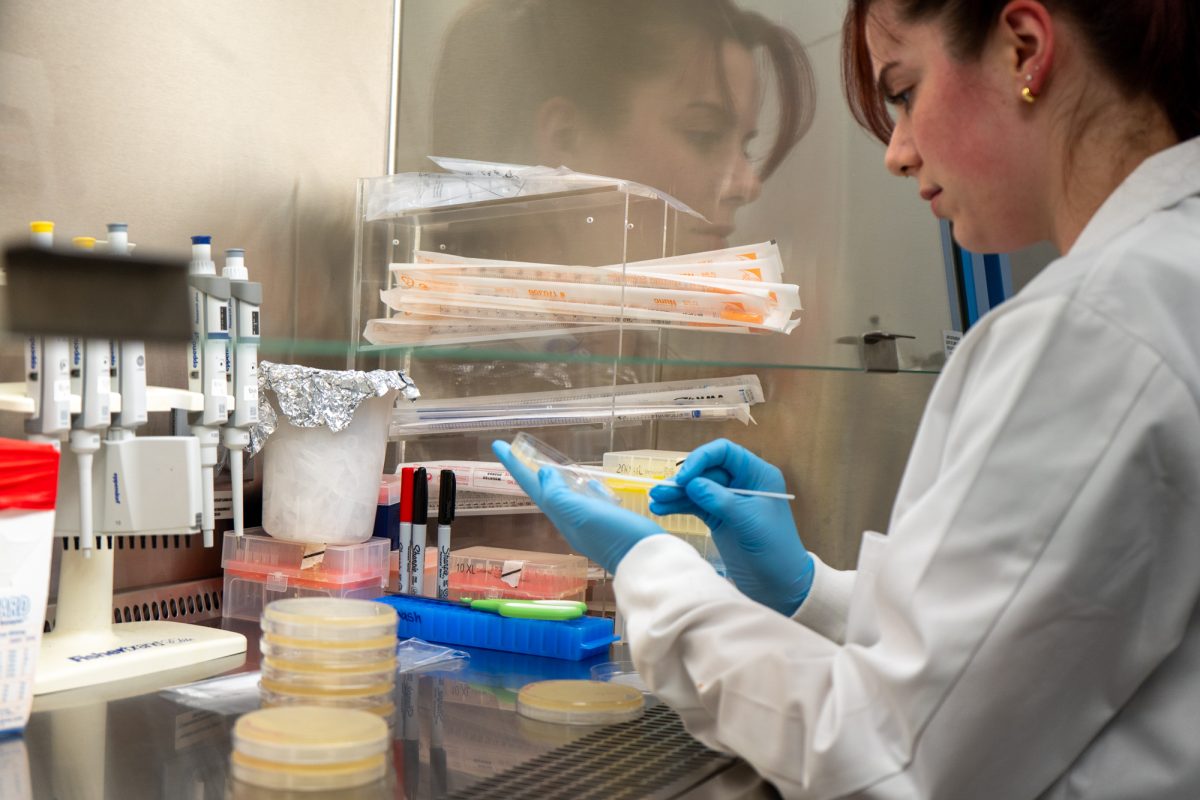

The soft-boiled egg was the food of choice to demonstrate how the proteins in the egg respond to temperature by unfolding and denaturing, and Weitz put eggs in immersion cookers set at three temperatures, each differing by two degrees Celsius. He mentioned the use of sous-vide cooking, or cooking using a vacuum bag and constant temperature bath.

“With sous-vide cooking, you can cook an egg for as long as you want if you get the temperature right,” Weitz said. “The proteins are all folded up and fluid, when you heat them the proteins unfold and run into their neighbours but they are really sticky and they stick to each other.”

Tatiana Erukhimova, physics professor and the event organizer, said this was the first-ever physics of cooking demonstration A&M has hosted in conjunction with the Physics and Engineering festival.

“The goal is to bring people together and celebrate science, and we want people to have fun and learn something without even knowing that they are learning,” Erukhimova said.

Karen Butler-Purry, associate provost for graduate and professional studies, said she was impressed by the interesting cooking methods on how to simplify your time and effort.

“I found it quite interesting that they took something really complicated like physics and made it enjoyable such that the masses could understand it,” Butler-Purry said.