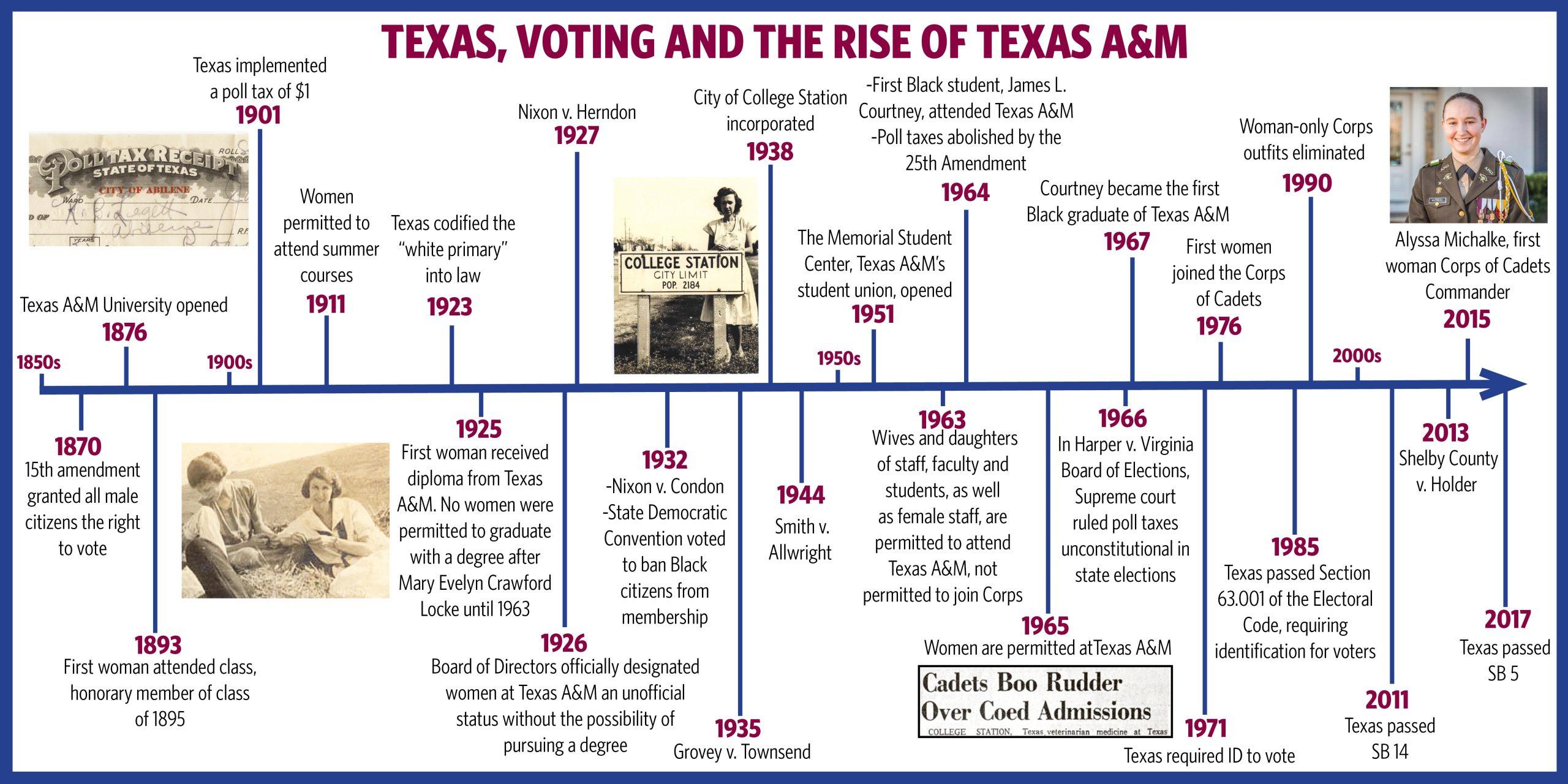

After Reconstruction, the “white primary” in Texas was status quo until 1923, when Article 3107 of the Statutes of Texas codified it as law. The “white primary” would prevent Black Democrats from having a voice in representation.

Three Black men would each challenge the law.

Lawrence Nixon, a Black physician from El Paso, sued after being turned away from voting despite having a poll tax receipt. In 1927, the Supreme Court ruled the law unconstitutional in Nixon v. Herndon, citing the Fourteenth Amendment.

Within months, Texas replaced the law with another that allowed primary executive committees to restrict who could participate in nominations, a de facto return to white primaries.

When Democrats passed a resolution, Nixon sued again.

In 1934, the Supreme Court again sided with Nixon, citing the Fourteenth Amendment. The victory was short lived. Another resolution instituting the white primary was passed by the Texas Democratic state convention to replace the executive committee.

Houston barber Richard Grovey sued, and lost. In 1935, the Supreme Court found in Grovey v. Townsend the Democratic primary, as a private organization, had the power to set membership requirements.

The white primary continued until 1944, when the Supreme Court overturned the Grovey decision in Smith v. Allwright, stating the primaries were an integral part of the electoral process. This was a victory for Black voters, but it did not mean the end of voter suppression.

In 1965, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act to protect and ensure the right to vote for all eligible citizens regardless of race. Section 5 of the VRA requires that certain states are subject to a preclearance requirement in the event of changing voting laws.

Section 4 determined which states were subject to Section 5. Texas was one of these states. The 2013 Supreme Court decision Shelby County v. Holder determined that Section 4 provisions were outdated and no longer applied. This decision effectively disarmed the VRA of the power to keep states in check.

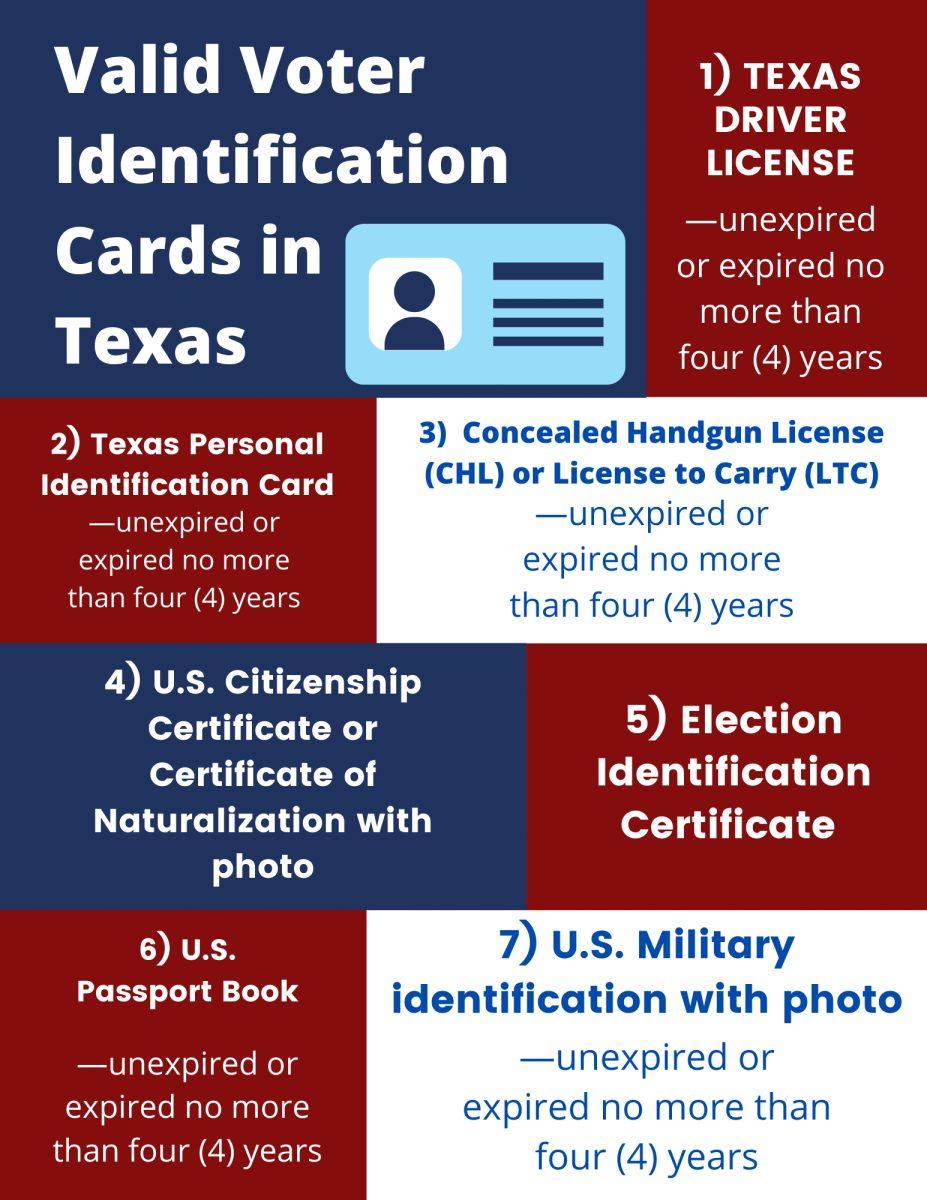

Within hours of the decision, then Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott announced that Texas would implement stricter voting ID requirements, a strategy historically used to suppress and disenfranchise minority groups. In 2014, the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals found the Texas law “racially discriminatory” and unconstitutional.

Today, SB 5, a new law, provides six alternative forms of identification citizens can use to vote.

Historically, Texas has had comparatively low voter turnout. Texas voter turnout has not been above 55 percent in the last 50 years. The U.S. median voter turnout rate was 59.3 percent in 2016.

This story is a collaboration between The Battalion and upperclassmen in Texas A&M’s journalism degree. To see the online copy of the “All Things Voting” print edition, click here.