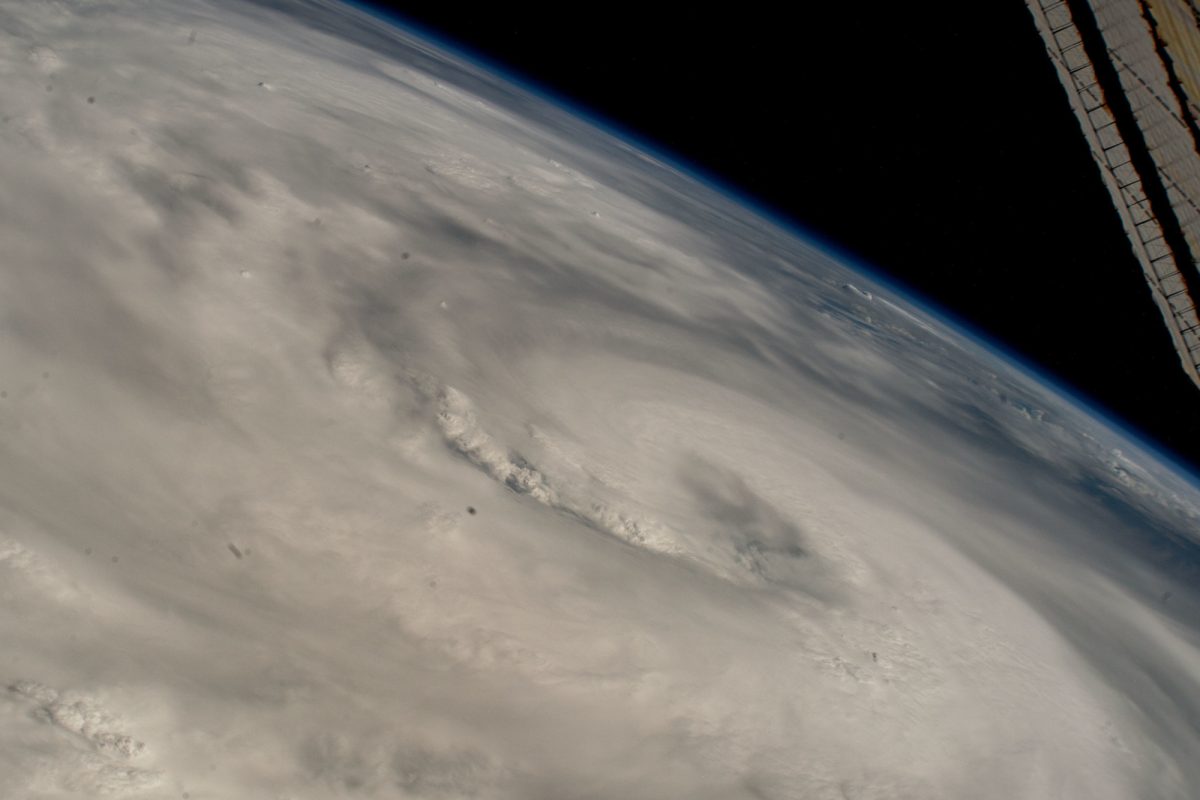

Hurricane Helene’s historic rainfall wasn’t random, according to research conducted led by John Nielsen-Gammon, the Texas state climatologist and a Texas A&M regents professor, who found that climate change likely boosted the storm’s strength and intensified its downpours.

Nielsen-Gammon’s new study links warmer ocean temperatures to record-breaking rainfall in storms like Hurricane Helene, which ravaged portions of Texas earlier this year. Researchers say it’s time to rethink storm preparations as climate change fuels stronger hurricanes.

His analysis of temperature records, storm data and rainfall patterns found that warmer ocean waters and changing atmospheric conditions may have amplified Helene and created ideal conditions for extreme rainfall.

“This study really highlights how our warming climate is creating the perfect recipe for more intense storms,” Nielsen-Gammon said. “The evidence suggests that, compared to past decades, today’s storms are packing much more moisture, resulting in these record-breaking rainfall events.”

For years, climate scientists have warned about the impact of greenhouse gas emissions, which drive temperatures higher and bring more frequent extreme weather. Now, Nielsen-Gammon’s study adds to a growing body of research showing these changes aren’t hypothetical.

“We found a clear link between higher ocean temperatures and the amount of rainfall during Hurricane Helene,” Nielsen-Gammon said. “When ocean temperatures rise, so does the potential for more moisture in the air, which can lead to heavier rainfall during storms.”

This link between warming oceans and heavier rainfall is part of what scientists call a climate feedback loop. As the Earth warms, ocean temperatures climb, adding moisture to the atmosphere and fueling stronger storms. The cycle poses a growing concern for coastal and urban areas that may not be ready for frequent, intense flooding. Nielsen-Gammon hopes his findings will shed light on how climate change influences hurricanes like Helene and encourage communities to take climate resilience seriously.

“With climate change making hurricanes like Helene stronger, we need to be proactive in educating people about the increased risks,” atmospheric sciences doctoral student Emmanuel Ibekwe said. “This isn’t just about forecasting. It’s about making sure people understand what these changes mean for their homes and communities.”

Ibekwe has followed extreme weather events closely through news reports and social media, where images of storm-ravaged areas along the Gulf Coast and other regions bring climate impacts into sharp focus. He believes education and public awareness play a crucial role in keeping people safe.

“If people understand the science and the risks, they’re more likely to be prepared, to evacuate if needed or to build their homes and communities in ways that minimize damage,” Ibekwe said.

In Hurricane Helene’s case, high sea surface temperatures and shifting wind patterns created ideal conditions for excessive rainfall. While hurricanes have always been part of nature’s cycle, studies like Nielsen-Gammon’s show that the intensity and frequency of storms are changing in response to human-driven climate change. For people in hurricane-prone areas, this means a greater need for disaster preparation, from infrastructure improvements to public education campaigns.

“There’s no question climate change made this storm stronger,” Ibekwe said. “When temperatures rise, everything from a hurricane’s wind speed to rainfall can intensify.”

Ibekwe emphasized that educating the public on climate science can support better policy decisions and safety measures. Even smaller efforts like improving drainage systems or building sea walls can make a big difference during major storms.

Nielsen-Gammon’s research raises broader questions about what future hurricane seasons may look like. While predicting specific weather patterns is difficult, scientists agree that the warming trend could mean more frequent extreme weather events globally. For regions that already face high hurricane risk, these changes could disrupt daily life, increase property damage and even lead to environmental displacement as some areas become less habitable.

Nielsen-Gammon emphasizes that public awareness is essential in adapting to the “new normal” of climate-driven extreme weather. While his work focuses on the technical side of climate science, he stresses that his findings are intended to benefit everyone, not just scientists or policymakers.

“People need to understand that climate change isn’t some abstract concept,” Neilsen-Gammon said. “It’s here and it’s changing the weather patterns we experience.”

Ibekwe echoed the importance of awareness, noting that educating young people, especially college students, about climate change’s effects can have a big impact.

“We have the data,” Ibekwe said. “We have the science, and now we need to get people on board with making real changes. When people, especially young people, understand what’s at stake, they’re more likely to support policies that protect the environment and prepare us for the future.”