On May 25, 2012, for her 21st birthday, Ana Parra mailed an immigration application to bring her deported father back to the U.S.

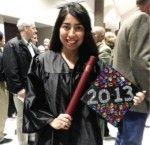

Parra, a Class of 2013 computer science major, and her two younger sisters were born to immigrant parents in the U.S. When Parra was 14, her mother died due to kidney problems. For a year, Parra looked after her sisters until July 1, 2008, when her father was deported back to Mexico because of an expired visa. On the day of her 21st birthday, she sent the immigration application to bring her father back to be with his family.

“My father shouldn’t be punished for staying in the United States to take care of his family who had just lost a mother,” Parra said. “As soon as I was of the legal age to be a petitioner, I sent the application.”

By February 2013, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services approved Parra’s application and her documents were sent to the National Visa Center. Parra received a notice from the NVC in March stating that her father was eligible for further processing. Parra said she was supposed to serve as an interpreter during her Spanish-speaking father’s interview in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico. Just before the interview, a Mexican police officer told her she would not be able to go into the interview with her father.

“He didn’t tell me why, he just said I couldn’t go in,” Parra said. “He told me if the interviewer needed any help translating, she would come get me. She never did, although my father said he asked her to several times.”

The case handler informed Parra that because her father was deported in 2008, he would not be eligible to return until 2018.

“I just want him back,” Parra said. “I hardly get to interact with him other than phone calls and we got really close after my mom passed away.”

Bob Libal, executive director of Grassroots Leadership, an organization that works toward ending social and economic oppression in the United States, said that unfortunately Parra’s case is

not uncommon.

“It’s very difficult for people who are in mixed status families to gain status,” Libal said. “Often times what people will say, ‘Why didn’t you just come legally or get legal when you got here?’ The truth is it’s very hard to have legal status and to gain legal status. I wish that this was a case that was unusual but those cases are very common.”

Parra said she was supposed to leave for a job in Seattle in two weeks, but requested to have the date pushed back until March 17 to have more time to try and bring her father home. Parra also created a website to give a voice to her family’s story.

“I’m just trying to get the word out and get as much attention on the issue as possible,” Parra said. “There are a lot of people in my situation and I want it to be recognized.”

America’s deportation system, Libal said, has had a similar format to its current one for almost 20 years.

“The system in the United States now is deporting almost 400,000 people every year, so this is a very large system,” Libal said. “Much of the legal basis for that system goes back to 1996 and a couple of immigration bills that were passed in the wake of Oklahoma City bombing, which initially was suspected that it was done by people not from the United States before it turned out that it was done by Americans. Those laws really changed our system from a presumption of being able to stay in the country to the presumption of deportation. Now people can be deported or contained in a prison-like setting for a variety of reasons.”

Dianne Kraft, diversity education coordinator for the multicultural services department, said the issue disgusts her.

“So many families are separated because of this,” Kraft said. “It’s sad how unnoticed these things go and how few people are aware of this issue.”

Libal will be speaking at Texas A&M from 11:30 a.m. to 1 p.m. Wednesday in Rudder 401 to address immigration issues and discuss how Grassroots Leadership makes an effort to slow and stop immigration detention and deportation.

While Libal said the current status of American immigration is flawed, there is also hope for the future.

“This is obviously something that’s very impactful and I think very depressing in many ways, but I also think that there’s a glowing movement of people in Texas and around the country that says that this isn’t something that we want as Americans – that people are trying to do something to change this,” Libal said. “I think that’s the hopeful part of the story is that people who are impacted by these policies and other people are standing up and saying they don’t want this type of thing to continue.”

Former student’s story brings national issues close to home

February 11, 2014

0

Donate to The Battalion

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas A&M University - College Station. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

More to Discover