“You know, this school really needs a group, and if nobody else is going to start one, why don’t we?” — Sherri Skinner

Whether due to shoddy record-keeping, faded memories or Texas A&M’s famed self-regard, the early days of Gay Student Services (GSS) — like much of A&M’s history — have mostly been mythologized. As such, it can be difficult to fix the finer details of how the group came to be.

Local lore has it that, as a prank, several students posted flyers around campus for a non-existent gay student organization to meet at the Memorial Student Center (MSC). When gay and lesbian Aggies showed up for the meeting, they found no one but themselves. Undeterred — but for the first time in the company of those in similar circumstances — the story goes that this group founded GSS. Still another telling (this one supported by several press clippings as well as at least two documents published by the university) claims that, in 1976, three Aggies founded the “Gay Student Services Organization.” They are identified as Sherri Skinner, Patricia Wooldridge and Sara Herlick.

Like most myths worth keeping, these stories get important generalities correct. Three stand out: the homophobic nature of A&M in the mid-1970s, the critical role women played in the organization’s founding and the “tough it out” attitude gay and lesbian Aggies adopted to get through the day. But these myths should not be relied upon as either accurate or complete history.

For one, in an interview performed by Kevin Bailey (GSS’s historian in the early 1980s who donated much of his work to Cushing Library), Skinner says the group was founded in 1975, not 1976. Second, while it is true that flyers were posted, there is little reason to think they were a prank. Skinner herself wasn’t so sure. The flyers were for a local meeting of a national gay rights group, not, as would be more likely for a school prank, a gay student organization. Additionally, the flyers were posted in the week leading up to Parents Weekend, and it made little sense for a schoolwide joke of this sort to occur immediately before Parents Weekend instead of immediately after. Either way, according to Skinner, members of the Corps hastily removed the flyers.

But the myth does get one detail correct: When Skinner showed up at the advertised location, no such meeting was taking place. (Both the source of the flyers and the reason for the meeting’s cancellation have, unfortunately, been lost to history.) Nevertheless, news of the meeting had spread, and Skinner soon found herself in the company of students looking for the same gathering.

It is here what thread of truth the myth retained unravels, for if this meeting was the founding of GSS, the organization could not have been founded by Skinner, Wooldridge and Herlick — at least not entirely.

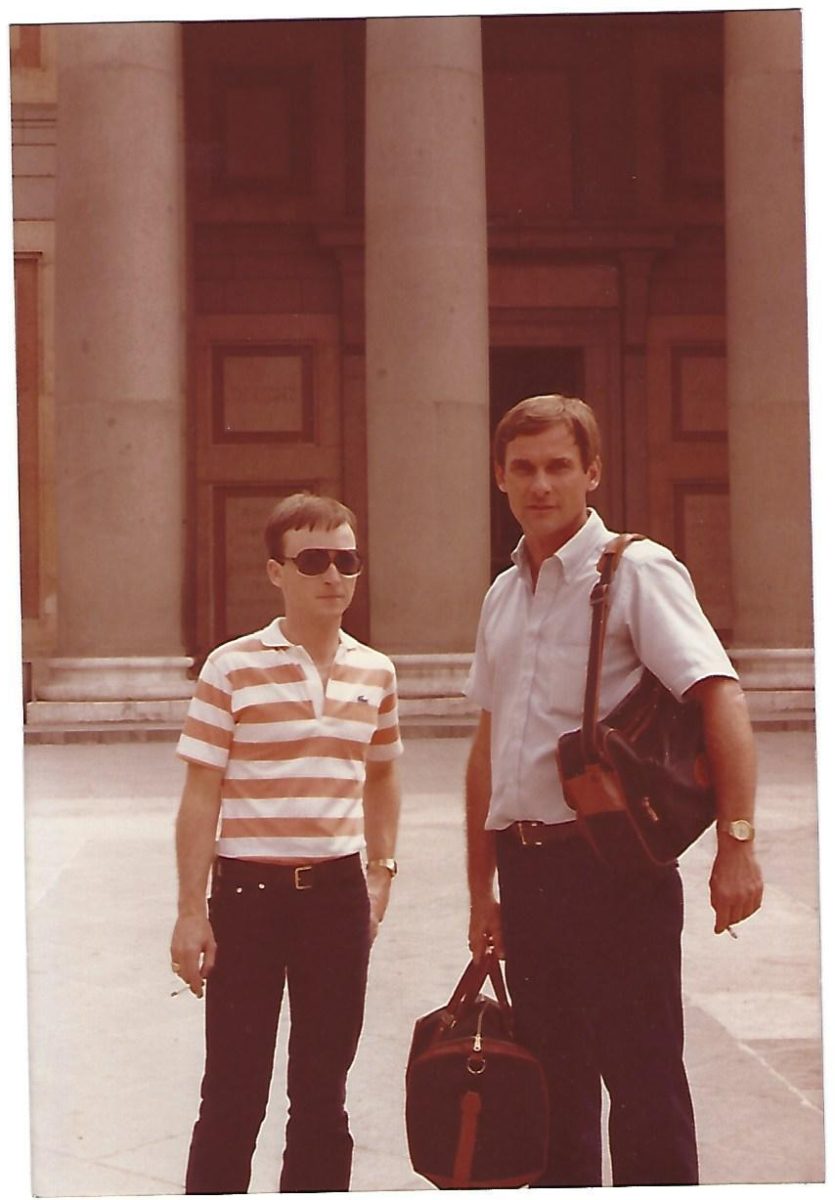

First, in an interview conducted for this piece, Sara Herlick said she was not present that night. She came to the group shortly thereafter. Second, Skinner’s recounting to Kevin Bailey makes no mention of Wooldridge, referring only to “a couple of other girls” — and though it is possible these “other girls” included Wooldridge, Skinner also says that “originally there were three men and three women.” Indeed, all recountings of GSS’s founding — both those present in Cushing library as well as interviews conducted for this article — make mention of the 50-50 split between gays and lesbians. Therefore, while GSS’s gender balance was noteworthy at a school still struggling to overcome its all-male roots, the list of GSS’s founders should include both men and women.

Finally, though judgments vary concerning when this collection of students became a full-fledged organization, one thing is certain: When the group did form, they chose the name “Alternative,” not Gay Student Services Organization. According to Skinner, it was an attempt to “get people to think about the concept of being an outcast.”

* * *

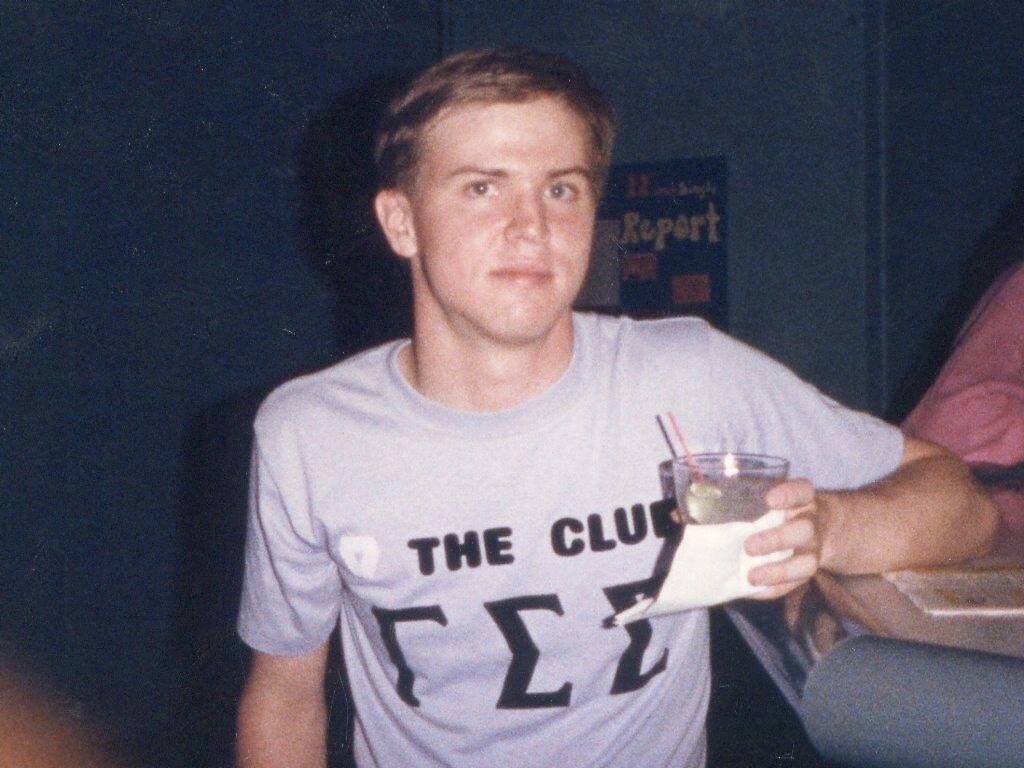

Michael Garrett found the group (not yet Alternative) in a different way.

For the sophomore transfer from Notre Dame in the 1974-75 school year, A&M came as a culture shock. Compared to the more diverse Notre Dame, Garrett found A&M “predominantly male,” “very white,” “very conservative” and “very homophobic.” So Garrett — out to himself but not to friends and family — kept his head low, focusing mostly on his schoolwork. He wasn’t at the MSC that night, and as far as he knew, he didn’t know anyone who was gay at A&M.

But as luck would have it, the first gay Aggie Garrett met was one of his classmates. They ran into one another at a gay bar near that school down the road. The classmate, whose name Garret did not provide, lived in an off-campus house with several other gay students. Because of its large living room, it functioned well as an informal hangout. It was not uncommon for furniture to get pushed against walls, music to start playing and everyone to spend the night dancing.

“Through him,” Garrett said, “the men had kind of an informal group, and apparently the women did, too.”

The two groups eventually coalesced, and eventually merged with the students who had found one another in the MSC. From then on, recruitment was like gravity: The larger the group became, the easier it was to gain more members.

Taking inspiration from the feminist organizations of the time, they participated in consciousness-raising and rap groups. However, their most important role was to serve as a makeshift family for members who were not out to their relatives.

(I’ve got a story for you, Ags:

Though it might validate a crude stereotype to mention this, soon after Alternative began, the local feminist group shut down. “It turns out a lot of the women were gay!” Skinner said in an interview with Bailey. “Oh, gee. Fancy that! We didn’t have a lot of activist straight women at that time. If you were angry enough to do something about [sexism], it was because you knew, in your heart, that you weren’t gonna have a man to depend on for the rest of your life, so you better do something.”)

It was from these informal get-togethers that Alternative was born. However, it is difficult to determine when this haphazard collection of students (who spent equal time dancing and learning) metamorphosed into an organization proper. Indeed, those interviewed for this article gave conflicting accounts, indicating the idea was batted around several times before coming to fruition. Still, Skinner’s, Garrett’s and Herlick’s judgments all have one thing in common: the more the group set out to accomplish external goals instead of internal ones, the more the name Alternative stuck.

They operated as something of a semi-secret community organization, and in keeping with their commitment to consciousness-raising, Alternative put up two flyers around campus:

The first was a quote from Elsa Gidlow, author of the first collection of lesbian poetry published in North America. It read, simply, “Being different in a dog’s world is no disgrace to the cat.”

The second was a poem by Linda Lachman entitled “Is Love Wrong?” It reads:

If you are black and I am white

If you are female and I am too

If you are old and I am young

If you are Arab and I am Jew

Let any man defend his LOVE for any man.

Who dares to call LOVE wrong?

For only HATRED is ungodly.

Only HATRED is not strong.

If my soul reached out to yours

And your soul matches mine

Then what matter what the body be—

Let us love and not define.

As can be seen, the scant references to homosexuality (such that they existed) were obscured by generalities and abstractions. They were there if someone knew where to look but coated in a thick gauze of plausible deniability should the wrong person ask the right questions.

The posters were simply signed with the group name “Alternative,” though what exactly Alternative was remained unclear. The posters themselves certainly didn’t say, and any enterprising student nosy enough to check the university records would have left unfulfilled. Alternative’s inaugural class hadn’t registered with the school in part to avoid a paper trail. For an organization of gays and lesbians (the majority of which were not out to their families), documentation was a no-go.

But though it took keen eyes to notice, there was a clue to (and in) Alternative’s designs. Earlier in the decade, the Greek letter lambda had come to symbolize gay liberation. Anyone familiar with this would have noticed the “A” in Alternative was stylized as such (λlternative) and would have rationalized that this was not a coincidence.

Once again, the posters’ meaning may not have been clearly stated, but their purpose was clear as day to those in the know. Indeed, the plan seemed to work. According to Skinner, “A lot of people thought we were a religious organization.”

The second external initiative was the beginning of what would become known as the “gay line.” A hotline for students both gay and straight, it had four purposes:

- As a referral service for medical, therapeutic and academic counseling for gay and lesbian students.

- As a resource the A&M community could turn to for information about gay life.

- As a roommate service for students who wished to live openly in their own homes.

- As the front desk of “Speaker’s Bureau,” through which teachers, student organizations and the community at large could request speakers to explain what it was like to be gay.

Sara Herlick, as sunny and voluble as anyone, was a volunteer for the Speakers Bureau. During her time, she became exceptionally skilled at speaking in front of hostile crowds — mostly by seeming fun and reasonable.

As a general rule, when she was invited to speak to a class full of students, she told the professor that the day’s lecture had to be optional. “I just felt like it was fair,” Herlick said.

She remembers one class vividly. There was a student in the back of the lecture room, not taking well to what she was saying.

“He was in the back seat, and he was just sitting there the whole time and just talking to himself and had his hands clasped. I looked at him and said, ‘Are you all right?’

“‘I’m going to hell. I’m going to hell. I’m going to hell,’ [he said.]

“I said, ‘What do you mean?’

“He said, ‘I’m in the same room as—’

“I could not believe how terrified this kid was of me being in a room with him. [I had] no weapons, no nothing. Just me.”

Herlick looked to the professor, “Did you tell them that they had to come to class?”

The professor had. And so Herlick turned back to the student and said, “If it means that much to you, you’re allowed to leave. I am not about to send anybody to hell.” The kid left, but the class laughed. The ice was broken.

(I’ve got a story for you, Ags…

Herlick was a master at breaking the ice. Once, a student in a class to which she was speaking said to her, “Well, it’s just terrible that our tax dollars go to your education because you’re just such vile people, and you don’t even pay income tax.” To which Herlick, knowing she was speaking to a conservative audience, said, “You mean I don’t pay taxes? Holy shit, I bet everybody in the world now wants to be gay!”

Again, with her quick wit, she had gotten the attention of the room.

For Herlick, the plan was simple: “[I] just kinda had to keep the humor and let them know I was just a person like they were. It was no different. I pulled my pants on one leg at a time.”)

But it was while advertising the gay line that one of the most ignominious incidents in A&M’s history occurred. Unlike the previous posters, with their subtle references to homosexuality often interpreted as religious messages, the gay line’s purpose was clear. (And much like the flyers for the local meeting of the national gay organization, the members of the Corps had been tearing them down.)

According to Skinner, Garrett, and court documents, three Corps members approached two men in Alternative in the middle of the night. None of the Corps members were wearing their name badges. One produced a switchblade and, at knifepoint, forced the members of Alternative to go around campus and pull the flyers down.

(I’ve got a story for you, Ags:

In her interview with Kevin Bailey, Skinner adds a heretofore unacknowledged wrinkle that hasn’t been published before: Two of the Corps members didn’t expect the confrontation to go that far. When the third corps member drew the knife, they immediately left.)

At about the same time (though there is no evidence to suggest the two events were coordinated), university officials called the gay line: Alternative needed to take down their flyers.

Garrett puts it best: Even though the bulletin boards around campus were technically only for student organizations, “at that time, all over campus, the kiosks and bulletin boards and everything else, everybody and their uncle would have a flyer with little telephone numbers at the bottom. And so we did the same thing. That’s the way we advertised the line. We had a couple of professors contact us.”

Between the threat and the phone call from the university, the group had had enough. Their hands were being forced.

So Sherri Skinner, Michael Garrett and Michael Minton approached then-director of Student Affairs, John Koldus. They asked for what they called “limited recognition.” It was an attempt at something of a gentlemen’s agreement. Skinner, Garrett and Minton were not naive; they knew the university would have little, if any interest in granting a gay student organization full recognition. But as far as they were concerned, that was absolutely fine, even perfect. The founding members of Alternative had explicitly rejected the idea of becoming a student organization, preferring their privacy instead. The recent incident with the cadets — as well as a spate of death threats over the gay line — had only reinforced this preference. They didn’t want money. All they wanted was permission to access some commonly used elements of school property — e.g., bulletin boards.

But Koldus wasn’t having it. “He was very pleasant. He’s always been very cordial,” Skinner told Bailey. “[Yet] we could not convince the man orgies did not follow every meeting… He was an incredibly ignorant person. Pleasant. Very cordial. But just unbelievably ignorant.”

Koldus was upfront with the trio: Their application would not be accepted. Still, as a formality, Koldus forwarded the group to Carolyn Adair, the Director of Student Activities. Both Skinner and Garrett remember Adair — whose job, according to Skinner, was “to screen the riff-raff” — as being supportive. It was her suggestion, in fact, that Alternative become a purely service organization. The idea was simple: Much like the question of who could and could not use the bulletin boards, the rules about who could and could not have a student organization operated in a gray area. Officially, A&M did not allow social groups, but as a practical matter — with the exception of fraternities and sororities — this was rarely an issue. Adair and members of Alternative knew this would not be the case for the group, even though their nature presented exceptional circumstances. (In other words, while it was clear that Alternative performed both service and social functions, a reasonable person could argue that even the social functions — consciousness-raising, rap sessions, operating as a makeshift family — were still services.)

But everyone involved knew the coming process would not be “reasonable.” Alternative’s application, therefore, needed to be pristine. There could be no official cause for any reasonable person to deny them. With this in mind, it was best Alternative jettison its social aspects.

Navigating this reality is how the name Gay Student Services came to be. From then on, Alternative and Gay Student Services functioned as two separate entities — separate organizational goals, separate meetings and separate bank accounts. Politics and social gatherings (the “fun stuff,” Skinner called them) were reserved for Alternative. GSS did the “service, good-guy, boy scout stuff.”

(I’ve got a story for you, Ags…

Footnotes in the legal case put the final nail in the coffin on the topic of who founded GSS. If this moment is to be the organization’s founding, the footnotes describe Sherri Skinner, Patricia Wooldridge, Michael Minton, Charles George, Kathryn Kraatz and Michael Garrett as the founders. Additionally, this is consistent with interviews with those present at the time who said GSS and Alternative was equal parts men and women.)

Koldus was unimpressed. But instead of rejecting the application outright, he roped in the university’s general counsel. At that point, the application was put into a state of administrative purgatory. Officially, the given reason was that a similar case, Gay Lib v. University of Missouri, was working its way through the courts. But behind the scenes, something more underhanded was occurring. Court documents show that then-president Jack Williams wrote a memo stating A&M would not recognize Gay Student Services “until and unless we are ordered by higher authority to do so.”

The limbo took so long that Gay Student Services hired a lawyer who had handled a similar dispute at the school down the road. Garrett assumed there would be some “perfunctory back and forth. Just so that Koldus could say, ‘I tried.’”

But then, on Sept. 21, 1976, there came the pivotal meeting. According to notes taken by George and Garrett, Garrett asked Koldus for an update on their application. Was the school not required to give them a final answer?

Interestingly, Koldus shared in Garrett’s disappointment. The process was taking too long as far as he was concerned. He would have preferred to simply deny the application and then later apply any new legal rulings that came up. But as a university official, he had to follow the general counsel’s advice.

“This has become a legal chess game,” Koldus said. “We have made our move. You have a legal move which would be inappropriate for me to comment on. Your attorney can advise you what to do.”

And then, as pleasant and cordial as Skinner described him, Koldus let the group know that his door was always open.

He even wished them good luck.