Aggie biologists are joining forces with the University of Pennsylvania to solve the mystery of sleep.

While conventional wisdom suggests eight hours is the universal standard for a good night’s sleep, the optimal amount varies greatly between individuals for reasons not entirely known. Alex Keene, Ph.D., professor and department head of biology at A&M, said part of the reason why knowledge of the genetics of sleep has been limited is due to the time-consuming nature of conducting sleep experiments.

“You can’t go out there and basically bring every human into the sleep lab,” Keene said. “It’s really time-consuming, right? You have to hook them up and people sleep overnight.”

However, the recent popularity of genetic testing kits such as 23andMe and the success of the UK Biobank, a database started in 2006 that collects information on human health and genetics, has provided researchers with an unprecedented volume of human genetic information from willing volunteers. This development enabled Struan Grant, professor of pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania, to analyze the human genome and produce a list of one hundred genes that are potentially involved in sleep regulation.

“All the gene hunting that’s gone on for the last couple of decades ha[s] revealed very strong genetic signals in the genome,” Grant said. “We inferred the relationship between the [sleep trait] variants and a gene … we then emailed those genes to Dr. Keene.”

Prior research has shown many sleep mechanisms are shared among all animals, suggesting the genes that play a role in their functions are also shared between species. With the Penn researchers having made a list of candidate genes, Keene said the A&M lab could now zero in on which gene played the biggest role in sleep regulation.

“We at Texas A&M got that list of genes [from Penn],” Keene said. “We went and we knocked them down one at a time in fruit flies. Then we can screen [them] and see which ones regulate sleep.”

For an organism that could serve as a model for humans, the A&M lab decided on fruit flies. Justin Palermo, a biology Ph.D. student, said fruit flies were used because sleep mechanisms are shared between them and humans.

“For us, it’s very important that we show that they actually sleep, and it’s been accepted that they sleep in the same way humans do for the last 20 years,” Palermo said. “We were able to identify genes that were conserved from flies to humans and also affect the same behavior.”

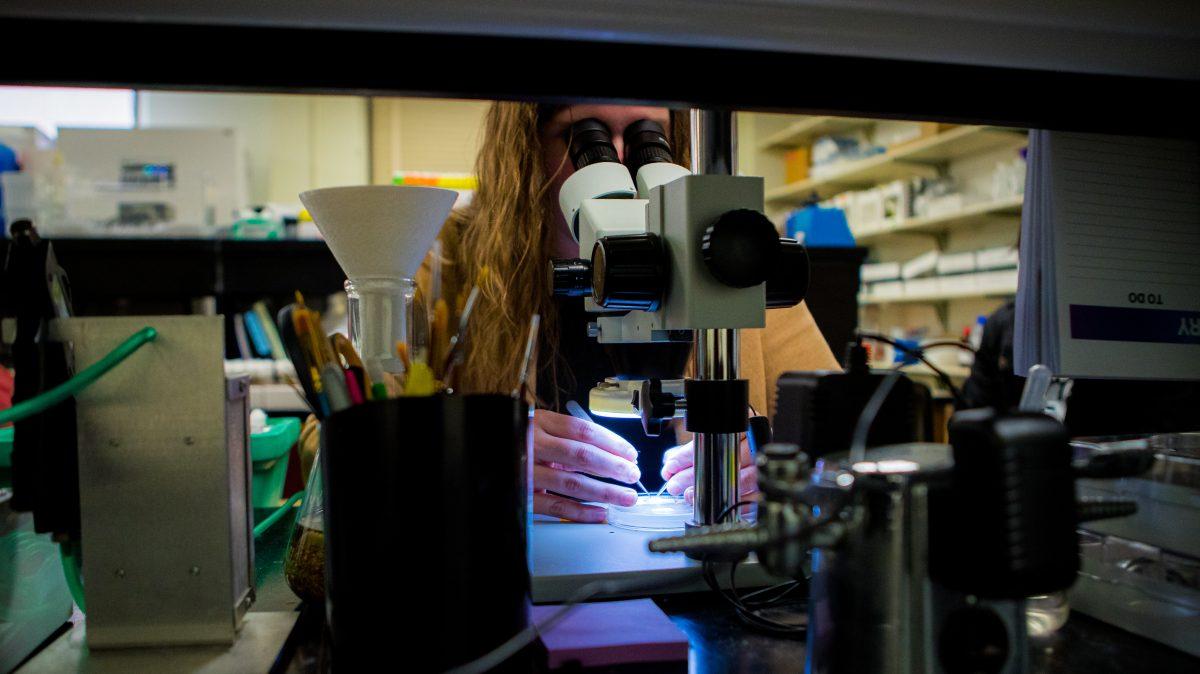

Elizabeth Brown, Ph.D., a research scientist in the biology department, said the team used a genetic editing technique known as clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats, or CRISPR, to silence certain genes in select fruit flies and compare their sleeping patterns to fruit flies with normal genes. The team collects data by holding the flies in an enclosure that automatically records their sleep durations and movements.

“[We have an] incubator full of flies where we’re recording sleep,” Brown said. “We’ve got this computer connected, and it measures sleep or it measures activity every minute of every day.”

The team zeroed in on a gene called Pig-Q, Brown said. The team found that fruit flies with a suppressed Pig-Q gene slept more than fruit flies with a normal Pig-Q gene, but had the same level of physical movement while awake.

“When we silence Pig-Q, we can look at the effects on sleep,” Brown said. “They sleep more, but they have the same measurements of activity.”

While the team has, as of yet, only experimented with suppressing the Pig-Q gene, Keene theorizes another mutation might cause the fruit flies to need less sleep instead.

“When … you knock [the Pig-Q gene] out, [the fruit flies] sleep more,” Keene said. “So you can imagine at higher levels, they would sleep less. Sleep is kind of bi-directional, and a lot of these genes can impact sleep in both ways.”

Once the link between sleep and Pig-Q had been established among fruit flies, the experiment went back to Philadelphia, where Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia researcher Amber Zimmerman, Ph.D., conducted an experiment that found a link also existed among zebrafish. The gene’s function being shared between flies and fish suggests humans are likely to possess it as well, Zimmerman said.

“[Pig-Q led to longer] sleep in both the flies and the fish, so it was conserved in both invertebrates and vertebrates,” Zimmerman said. “That suggests that it’s … a very strong candidate for moving back to human studies and trying to determine its regulatory role in controlling sleep.”

Keene said the next step for the experiment is to analyze the genetic databases prepared by the Penn researchers to find humans with similar mutations in the Pig-Q gene and study their sleep patterns.

“The beauty of it is you get a list [of sleep-causing genes] from humans, and then you target them in fruit flies,” Keene said. “Then you can circle back to humans. There are humans out there with rare variants in these genes, and then you can go out and if you can find them, you can bring them into the sleep lab and measure their sleep.”

Sleep deprivation, Keene said, is alarmingly prevalent and has been conclusively proven to have a myriad of negative effects on human health. Keene said he hopes this research and other developments in the understanding of sleep can contribute to broad improvements in society’s health outcomes.

“A third of people suffer from some form of insomnia … Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases, heart disease, diabetes is a big one, obesity and all of these are associated with lack of sleep,” Keene said. “It’s pretty clear that if we can get people to sleep better, we can cure a lot of these sleep-associated disorders.”

Beyond sleep, Keene said the breakthrough demonstrates the power of collaboration in science.

“What I’m most excited about is just the power of collaborative science,” Keene said. “We never would have been able to mine human genetic databases and pull out the genes and come up with this paper on our own. I think just by developing these collaborations, we can really advance science in a way that we couldn’t otherwise.”