Texas A&M astronomers and their international partners announced the discovery of the most distant gravitational lens this summer — a galaxy that existed 9.6 billion years ago whose mass is large enough to “bend” the light passing through it, much like a magnifying glass.

Gravitational lenses at that age and distance were previously unheard of, and evidence of the lens’ existence was originally thought to be measurement error in an unrelated study. It would take two observatories and international collaboration before astronomers confirmed a hunch — there was more to their data than met the eye.

An Astronomer’s Bet

It was during the winter of 2012 that Kim Vy Tran walked into the office next door with a stubbornly inconsistent data set. Tran, a physics professor at Texas A&M, had just returned from the Keck Observatory in Hawaii where she had measured the distances of individual galaxies in a cluster estimated to be 10 billion years old.

Most of the galaxies were in the right place and acted as predicted, but one did not.

“When I took the spectrum, I saw a fingerprint of hot hydrogen gas, which was completely baffling because this object, from all our previous studies, shouldn’t have had this at all,” Tran said. “It was really surprising because we were expecting to see this very old, quiescent (galaxy) and then we saw this imprint of very hot hydrogen gas which is associated with lots of star formation.”

To complicate matters more, the galaxy appeared to be even farther then estimated. Seeking a second opinion, Tran went to collaborator Casey Papovich, a Texas A&M physics professor whose office is adjacent to hers in the Mitchell Physics Building. Papovich eventually bet Tran a dollar that they were looking at something more than just a galaxy.

“We looked hard at the data, (and) we actually had to pull up some Hubble Space Telescope imaging, which showed a faint blue fuzz adjacent to the red galaxy,” Papovich said.

Puzzle Pieces

The Hubble images gave Tran and Papovich a clue that would lead to the eventual discovery. While images from the Keck Observatory showed a single blurry galaxy, Hubble’s space-based observations resolved the data into two distinct objects.

“The original galaxy was where we thought it would be, and then this fingerprint of hydrogen gas was actually farther away,” Tran said.

Hubble confirmed what the two astronomers had thought — they were looking through a gravitational lens.

News of the discovery was shared with Kenneth Wong, a postdoctoral fellow at the Academia Sinica in Taipei, Taiwan, who modeled the galaxy’s lensing. In order to compensate for the gravitational effects of other cluster’s galaxies, Wong looked to previous measurements taken in the same slice of sky.

“We were able to estimate the effect of the galaxy cluster by using constraints from previous X-ray observations in this field, and therefore correct our model for its effect,” Wong said.

A Rare Find

Tran said stumbling upon a gravitational lens was very surprising — not only do the galaxies have to be perfectly aligned to produce a lens, but 9 billion years ago most galaxies were not large enough to act as lenses.

“The universe is mostly empty, and the chances of that happening are really, really small,” Tran said.

A galaxy needs to be massive because gravitational lensing is really an effect from general relativity, Tran explained.

“Matter tells space-time how to curve and space-time tells matter how to move,” Tran said, quoting physicist John Wheeler. “For the most part we think of photons as traveling along straight lines because they’re massless. But they’re moving through space, and if space is distorted then it has to follow that distortion.”

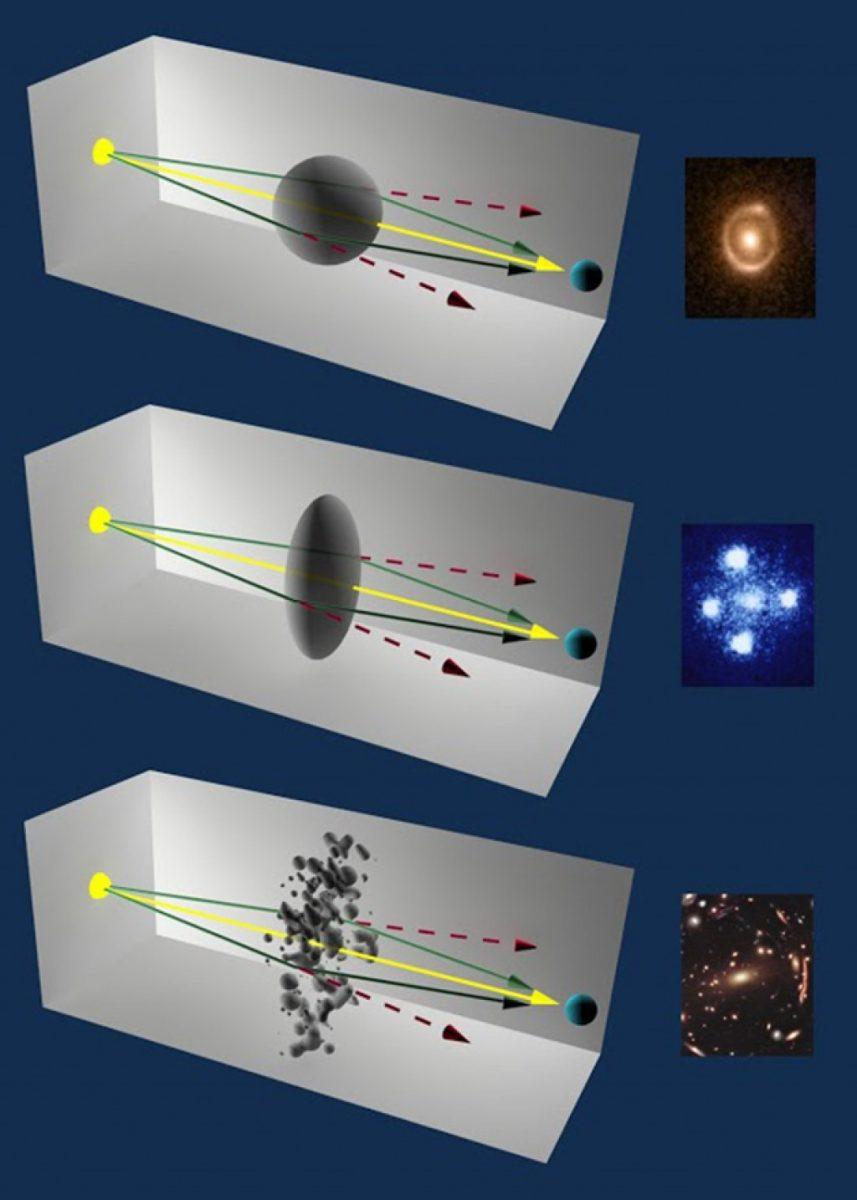

If a cosmic object is perfectly aligned behind a large-enough galaxy, its light will follow the distortions and the object appears to be viewed through a lens. Gravitational lenses are evident from the arcs they leave across deep-field observations — a trait readily apparent in the Hubble images Tran and Papovich referenced.

Tran said lensing is a valuable phenomenon because astronomers can use it to easily measure a galaxy’s total mass. This number can then be compared to other data to find an elusive measurement — the amount of dark matter present.

“We are either incredibly lucky or [lenses] are actually a lot more common than we thought,” Tran said. “They may find many of them, many more than anyone suspected. And so that allows you to immediately to do those two things: To study things even farther away, use those lenses as magnifying glasses, but also be able to weigh the galaxies doing the lensing.”

A&M astronomers, partners discover farthest lensing galaxy

September 1, 2014

A massive-enough object will bend light from a distant object to act like a gravitational lens. Telescope images are then warped into several patterns.

PHOTO PROVIDED BY ASIAA EPO

Donate to The Battalion

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas A&M University - College Station. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.