Seeing isn’t necessarily believing anymore.

Due to technological advances, physicists can say with a high degree of certainty, that everything that can be seen in the physical world is less than five percent of what is actually there. The other ninety-five percent is a combination of dark matter and dark energy. Dark matter is still highly ambiguous but, thanks to an international collaboration, it may soon be discovered in part with instruments under development at Texas A&M.

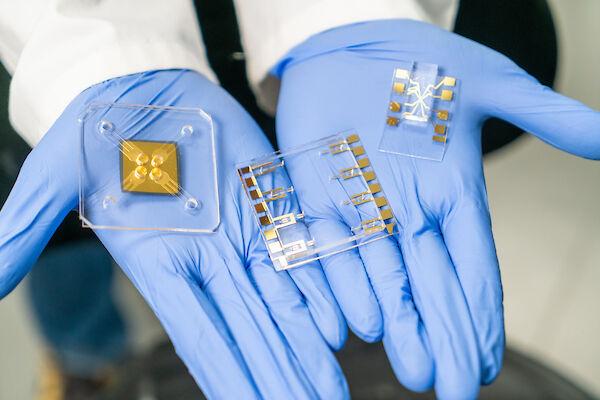

The Super Cryogenic Dark Matter Search, or SCDMS, will be one of the biggest dark matter detection experiments in history. It aims to use detectors of unparalleled sensitivity placed two kilometers underground to try and record dark matter for the first time. These detectors are being designed by a team of A&M physicists to determine the nature of dark matter.

Rupak Mahapatra, physics professor, along with professors David Toback, Rusty Harris and Nader Mirabolfathi, are at the forefront in United States’ efforts to find dark matter. The search is tough — humans cannot see or feel dark matter because its particles don’t interact with the observable world.

“Dark matter has no electromagnetic interaction,” Mahapatra said. “Of course they have gravity, but they also have a weak interaction. What this means is that if you pass a billion times a billion times a billion particles through your body, every once in a while, one will hit you.”

It is not a concept that is easily grasped, but Mahapatra explained it in simple terms.

“For example if I try to pass my hand through the wall, I can’t do it because there is electromagnetic interaction between the two. However, if I send a gamma particle at the wall, it will pass right through, because it doesn’t interact very strongly with the wall,” Mahapatra said.

Because of this property, dark matter is extremely difficult to understand, and expensive to research. There are two dark matter projects in the United States, and Texas A&M plays a major role in one of them.

SCDMS includes roughly a dozen universities, but only Texas A&M and Stanford make detectors that — in theory — will detect dark matter for the first time. These detectors need to be extremely sensitive, said Nader Mirabolfathi, a physicist at A&M involved in the experiment. He said they need to be sensitive enough to detect energy well under one billion times less than a mosquito landing on a person’s skin.

Mahapatra said the detectors use crystals made of germanium and silicon that, theoretically, will vibrate when hit by a dark matter particle. The small amount of energy imparted by the collision will cause a tiny change in temperature, eventually notifying the team that a particle passed through.

“These sensors can detect very slight vibrations as a change in temperature as small as a few micro-Kelvins,” Mahapatra said.

The crystals are expensive, and when all the costs are added up to make one of the detectors, the result is a price tag of roughly half a million dollars.

“These detectors are truly the best in the world,” Mahapatra said.

The unheard of sensitivity of the detectors, while necessary, presents a challenge to the experiment — it can detect miniscule events that could throw the experiment off.

“Our detectors are so sensitive, that things that would not be background [noise] for other experiments are background for us,” Mirabolfathi said.

Due to this, the current experiment is conducted in Soudan Underground Laboratory in Minnesota, to block these “background” cosmic rays from interfering with the detectors, but eventually will move to a facility called SNOLAB in Sudbury, Canada. At the new location, the detectors will be two kilometers underground. The aim of this is to keep nearly all unwanted rays away from the detectors.

There will be a total of about 60 kilograms of detectors, with each detector containing about 1.5 kilograms of Germanium and 0.6 kilograms of Silicon.

Since each individual detector is so valuable, significant time is put into making sure that they work correctly, but at the current pace, the SNOLAB experiment will be ready to begin in three years.

Texas A&M research project in pursuit of elusive particles

May 3, 2015

Donate to The Battalion

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas A&M University - College Station. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.