T

here is something magical about “Steve Jobs.” Directed by Danny Boyle and written by Aaron Sorkin, “Steve Jobs” carries an energy that most films only dream of.

The film centers around three product premiers — one in 1984, another in 1988 and the last in 1998 — but the turmoil that Jobs endures before each reveal make up the majority of the film. It is a structure that is both unconventional and effective. It is one that begs the question — in a two-hour movie about an individual’s life, what do you show and what do you cut? Do you go for an all-encompassing depiction, or do you zero-in on specific moments?

“Steve Jobs” does the latter, eschewing stories of his fight with cancer or the creation of the iPhone and focusing on Jobs’ relationship with his daughter from 1984 to 1998. This decision grounds the film in humanity, a necessity for a film about someone rumored to be cold and difficult to work with.

It is impossible to discuss a work by Aaron Sorkin without mentioning the dialogue. If you have seen “The Social Network,” you know what I am talking about. It is impeccable, rapid-fire, non-stop and some of the most real, conversational dialogue featured in film. This is, however, a double-edged sword, because anyone coming to “Steve Jobs” expecting any sort of action or thrill may be disappointed. In an Aaron Sorkin film, the dialogue is the action, the conversations are the battles. Sorkin knows how to build tension through the subtlest infractions: The tone of a word, the look on someone’s face or the composure of someone’s stance. It is full of rich detail and personality, but if watching talking heads for two hours bores you, this may be one to skip.

The director, Danny Boyle, has been known for his bombastic, larger-than-life style, evident by titles such as “Slumdog Millionaire” and “127 Hours.” He has the ability to take a static scene and make it feel kinetic, to provide context and emotion with camera movements. Some were worried that his style would clash with Sorkin’s writing, but thankfully Boyle dials back the flair and puts emphasis on the script, letting his actors and their lines do the bulk of the work. And this is a winning combo.

As I walked out of the theater, I was blown away that two hours had just passed. “Steve Jobs” absolutely melts time. I was ready for another couple hours of movie, and then the credits rolled. I cannot recall another film that had this effect, and this is the strongest articulation of the film’s quality I can muster. Boyle’s direction and Sorkin’s script come together in a beautiful way.

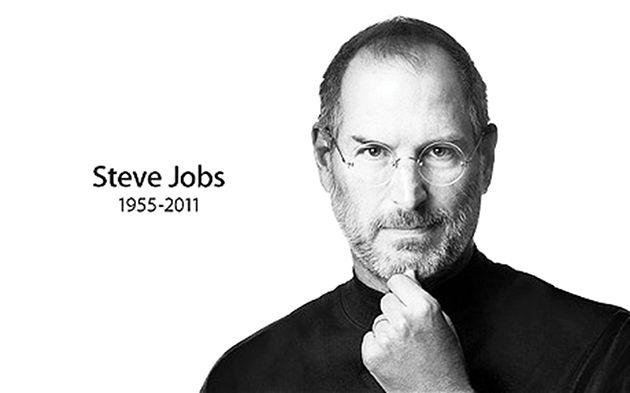

Michael Fassbender is also magnificent as Jobs. Without a doubt an oscar-worthy performance, Fassbender’s portrayal of Steve Jobs is so spot-on you will forget that he looks nothing like him. Similar to Jesse Eisenberg’s portrayal of Mark Zuckerberg in “The Social Network,” Fassbender’s Jobs is egotistical, prideful and totally imperfect. Watching Fassbender jump from one emotionally draining conversation to the next demonstrates his capability as an actor to portray multiple portraits of a man at his most stressed. Without a doubt, Fassbender carries this movie on his shoulders. Many other actors turn in fantastic performances, namely Seth Rogen’s Steve Wozniak and Kate Winslet’s Joanna Hoffman, but Fassbender is the undeniable star of the show.

The question on the table about the quality of this film rests on its comparison to a few other films. “Pirates of Silicon Valley,” which came out in 1999, is too outdated to be relevant, and the 2013 “Jobs,” starring Ashton Kutcher, has become the butt of jokes. That said, “Steve Jobs” is not as universally perfect as the 2010 “The Social Network,” but it is an expertly crafted film regardless.

Steve Jobs will forever be an important figure to technology. Many will argue that he was more salesman than creator, that his role in the advancement of consumer tech was exaggerated, and those people may be right. But his desire and his drive to get others to see technology as art is the reason we have the Internet in our pockets. This movie explains why that is something that can never be overstated.

Mason Morgan is an English senior and a Life & Arts writer for The Battalion.