Jim Schlossnagle has a vision:

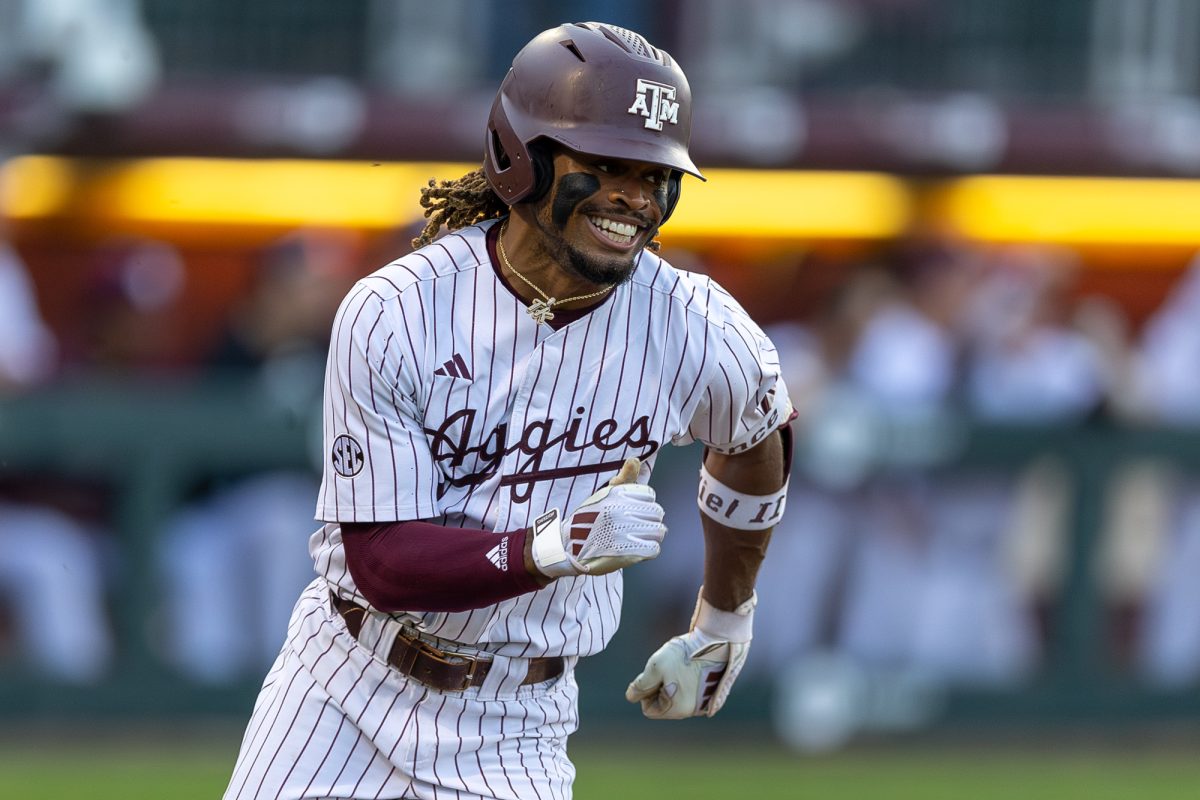

Texas A&M baseball returns to Olsen Field at Blue Bell Park, fresh from Omaha, Neb., with a shiny new addition to its trophy case. It’s a warm, summer day — Schlossnagle can’t stand the cold.

The stands are packed with Aggies, old and new. They might even have a party on the field. They’ll gather for a War Hymn to go down in Aggieland history.

First though, at each home game, 15,000 Aggie fans crowd the lining of the diamond at the intersection of Olsen Boulevard and George Bush Drive. What is prototyped through the Kyle Field gameday experience is translated into Schlossnagle’s new home.

It’s not about whether A&M won or lost; fans leave the concourse happy they showed up. They ate a 44 Farm’s Aggie Dog — it was great. Maybe they had a Karbach 12th Man Lager which was also great. They loved the music; they loved the dance team.

Maybe there was even a petting zoo.

An Aggie baseball game is the amalgamation of the theatrics of minor league baseball and the fervent fandom of college athletics. People fly in just to catch a weekend series. After the game, children can make their way to the third baseline and get an autograph from their favorite player. This all takes place tomorrow — Schlossnagle can’t stand waiting.

On a Zoom call from his office at Olsen Field in January, Schlossnagle detailed his vision. Through the window past his right shoulder, his vision was beginning to take shape in the form of expanded third baseline seating, metal-framed bleachers in place of the grass berm. Schlossnagle understands the impossibility of renovating the ballpark in its entirety by tomorrow, but if there is anyone to try to build Rome in a day — maybe two — it’s him.

Good, bad or indifferent, creating a community and coaching baseball is not Schlossnagle’s job — it is his lifestyle. Schlossnagle spoke matter-of-factly about his life, unless in reference to baseball, community, family or his faith; he lives through these pillars.

On June 9, 2021, Schlossnagle chased a fresh start on that lifestyle at A&M as he left the school he turned into a perennial college baseball powerhouse, Texas Christian University, after 18 years.

Now, Schlossnagle wants it all tomorrow. He wants to win tomorrow. He doesn’t want to let anyone down. He’s not patient, and he’d be the first person to tell you.

Impatience, though, is not a flaw in his character. Schlossnagle is driven by a sense of urgency, but he’s not panicked. His path to College Station is 36 years of collegiate baseball in the making. His path forward, aside from the seven-year contract he inked in June, is uncertain. His goals, however, are crystal clear.

“I don’t want to let anybody down. I know what I’m capable of, I know what this coaching staff is capable of,” Schlossnagle said. “I work from a point of, my job now is to not let anybody down, it is to meet the expectations that I have for myself and certainly this place has for this baseball program. I want it to happen tomorrow [despite] knowing that that’s usually not how that happens.”

In his relocation, Schlossnagle inherited a baseball program that owned the third-longest active NCAA Tournament appearance streak — 13 consecutively — until the end of the 2021 season. That roster and coaching staff has now been largely redone with Schlossnagle at the helm. Yet, without the past, none of the present would be possible.

Where it all started

The story of Schlossnagle begins in Smithsburg, Md., population of 2,967. Smithsburg High School’s parking lot fits no more than 100 cars and is sandwiched in between Smithsburg Elementary School and Smithsburg Middle School. Deep center field of the high school’s baseball field, where Schlossnagle played, lies just outside city limits — an area littered with farmland, forming an agricultural barrier on all sides of the town.

For a man who now eats, breathes and lives baseball, it hasn’t always been that way. Schlossnagle doesn’t have a lot of hobbies. He doesn’t play golf, and he fishes maybe five or six times a year. Sports have always been the center of his life through various avenues, but baseball was only the focus when it was his last option.

Throughout high school, he was a member of Smithsburg’s basketball team, its football team and its baseball team, in that order. Basketball was what he, and Smithsburg, truly excelled at during his senior season. Schlossnagle was the starting guard for the Leopards’ team that went to their first-ever basketball state championship.

In that game, Smithsburg faced Milford Mill, which had already knocked Schlossnagle’s alma mater out of the football playoffs. Down by one point with a chance to win the game, one of Schlossnagle’s teammates — unnamed for his privacy in trying times — passed the ball to the wrong team.

“He thought one of us was looking and he passed it; he literally passed it to the other team with less than 10 seconds left,” Schlossnagle said, though he didn’t sound thrilled to remember it.

When it came time for Schlossnagle to head to college, he chose to leave Maryland and attend Elon College in North Carolina. Schlossnagle didn’t necessarily have aspirations to be a professional athlete, but it wasn’t quite time for his playing days to end.

He chose to play baseball after adding “decent pitching support,” according to the Leopard Yearbook, to Smithsburg’s team, so he walked on to the team at Elon. It was here he met the man who would change his life.

Coaching Genesis

Schlossnagle was the editor of Smithsburg’s student newspaper and a high school sports stringer for The Herald-Mail in pursuit of a journalism career, ideally culminating in writing for Sports Illustrated.

After a year and a half, Schlossnagle was called into the office of then-Elon baseball coach Rick Jones.

“[Jones] said, ‘Hey, we both know you’re not playing in the big leagues.’ I said, ‘Yeah, thanks. I know,’ and he said, ‘I think you’d make a good coach,’” Schlossnagle said.

He was conflicted. He’d spent his entire life to this point as an athlete; the concept of stepping away from the field, the court and the diamond all within the span of two years was concerning to say the least.

Yet, he had built a deep relationship with coach Jones and ultimately knew he was right. Jones — who was also a pitcher — gave Schlossnagle a couple of days to decide. Schlossnagle returned sans journalism degree, now pursuing a bachelor’s in physical education.

“I said, ‘Go call your parents and come back and see me tomorrow or the next day.’ He came right back and said, ‘Coach, I want to coach,’ and that was it,” Jones said.

In 1989, after pitching for only one season, Schlossnagle stepped off the mound and placed his career in Jones’ hands.

“I didn’t want to give up playing. It’s funny how God works,” Schlossnagle said. “There was a lot of hesitation and concern, but I had a lot of trust in coach Jones and believed in him — he was already a super influential person in my life. I prayed about it and jumped in with both feet, and it’s turned out alright.”

When Schlossnagle landed from his leap of faith, he saw Jones take one of his own, becoming the assistant coach at Georgia Tech. Though the Yellow Jackets were not massively successful in the four years Jones was there, they appeared in the NCAA Regionals each year.

Schlossnagle, in contrast, spent the following three years as a student assistant pitching coach with Elon. The then-Fightin’ Christians built a 99-41 record en route to two South Atlantic Conference championships and a District 26 National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics championship.

After graduating from Elon in 1992, Schlossnagle joined Clemson as a pitching coach for the 1993 season. There, he studied under the late Bill Wilhelm in his last season with the Tiger, assisting in a 45-20 finish, an ACC championship and a semifinal exit in the Mideast Regional of the tournament. Jones’ Yellow Jackets were also knocked out in the semifinals of regionals in 1993.

In 1994, Jones left Georgia Tech to take a head coaching job at Tulane. His first call was to Schlossnagle, asking him to join the Green Wave as associate head coach.

“I can remember standing in the kitchen when Rick was offered the job at Tulane, and I said, ‘I’m not going unless Schloss goes.’ He’s very much a part of the family; he was like our son,” Jones’ wife Gina said.

Just as Schlossnagle trusted his coach when he told him to give up playing in the first place, he trusted his offer now. Without looking back, Schlossnagle joined Rick once again — the true start of coach Schlossnagle.

“Everything I know about, [how] to run a program, all-encompassing, literally everything, [Rick] is the basis for that. I owe him everything,” Schlossnagle said. “The basis of every single thing I am as a coach starts and ends with Rick Jones, and I’ll be forever grateful for that.”

Schlossnagle and Rick coached together for the next eight seasons. As Schlossnagle helped build Tulane, he also built a family with his wife Kami. The couple had two children, Jackson and Kati, who have played no small part in Jim’s evolution as a coach.

“Being a father is my No. 1 job in life — it’s the thing that means the most to me … Having children, there’s no question — it changes you,” Jim said. “I tell every person I can, ‘You think you love your girlfriend? It don’t even compare, buddy.’ When you have a child, the love and adoration and feelings that you have for this human being is … it blows your mind. Especially as they have gotten older, it helps you become a better coach, it helps you become more sensitive to players and what they go through, it helps you become more empathetic with the parents.”

Tulane went on to win three Conference USA regular season titles and four Conference USA tournaments. The Green Wave appeared in the NCAA tournament in all but two of the eight seasons, but never escaped Regionals.

Until they did.

In 2001, Rick Jones and Jim Schlossnagle’s Tulane entered as the national No. 5 seed and bombed its way through the Metairie Super Regional. Finally in Omaha, the Green Wave squeaked by Nebraska in the first round, 6-5. As all good things do, though, their College World Series run ended in the next round with an 11-2 walloping from Cal State Fullerton.

Regardless, neither coach had seen their last College World Series. Propelled by the success of Tulane, Schlossnagle began receiving offers to lead a program of his own.

Staying warm

After the trip to the College World Series, Jones was lined up to take an opening at Georgia and would have Schlossnagle succeed him at Tulane. Through a combination of issues with Georgia at the time and Tulane matching its offer, Jones stayed with the Green Wave, but Schlossnagle knew it was time to move up.

After 12 seasons of assistant jobs and a farewell to Jones, Schlossnagle started anew. He fielded calls from programs across the country interested in the young coach. He received an offer from his home state college, the University of Maryland; “Yeah, too cold,” he said.

Far from the cold, an opportunity appeared at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

“When [the job at] UNLV opened, I remember the lady who was in charge of the search committee there,” Jones said. “I made a call and she told me, ‘He’s going to be our fifth interview. We’ve had some really good candidates.’ I said, ‘Yeah, I’m sure you have, but let’s just you and I talk after you interview him.’ She called me back after the interview and said, ‘He’s on a plane now. But when he lands, we’re going to offer him the job.’”

Taking high hopes into high temperatures, Schlossnagle arrived in the desert in 2002 to take the helm of a program for the first time. Year one, for Schlossnagle, hit a decent mark that both he and the university could be proud of, finishing with a record of 30-30 — six more wins than UNLV had finished with in its last two years — and a ticket to the Mountain West tournament, where the Rebels finished fourth.

Then came year two in which Schlossnagle, acclimated to the nature of the desert and the nature of running his own team, began to familiarize himself with the commonplaces of his career: wins, postseason play and Coach of the Year honors. All of it fell into place for the first time in 2003.

Schlossnagle and the Rebels finished the 2003 season at 47-17, the second-highest win total in school history, and went on to win the Mountain West tournament and appear in the NCAA tournament. Though his team was knocked out in the Regional finals, Schlossnagle was named Mountain West Coach of the Year, and doors started to swing open.

Heading into the next season, Jim was yet again receiving calls from programs requesting him, now 32 years old, to turn their school around like he had done in Las Vegas. He was planning for the future.

He wasn’t going to go anywhere cold. He certainly wasn’t going anywhere he couldn’t build something special. He was ready to settle down somewhere more permanent.

“My wife at the time was from Dallas, and I had always kind of had my eye on getting back to Texas so that my children would grow up around somebody’s family,” Schlossnagle said. “I knew they weren’t going to grow up around mine because I can’t stand cold weather.”

So, born in a melting pot of climate, his family and baseball as more than a career, his new course was set.. In 2004, TCU wasn’t a powerhouse by any means, but it was a blossoming program in need of a new coach after Lance Brown, who spent the last 17 years at the helm, retired. Ultimately, Schlossnagle and his family packed up and headed to Fort Worth.

Joining TCU, Schlossnagle coached for two years in Conference USA — where Jones was still leading Tulane. In the 2004 season, Schlossnagle led the Horned Frogs to the most wins in a season in school history — a record he would break three more times. Tulane exited in the first round of the Conference USA tournament; TCU won it all and lost in the second round of NCAA Regionals.

In 2005, Schlossnagle upped the win total from 39 to 41. Jones won a career-high 56 games this season and his Green Wave won their weekend series against the Horned Frogs, 2-1. In the Conference USA tournament for that year, TCU and Tulane were scheduled to meet again with a conference title on the line.

“We were supposed to play in the conference championship game, and it rained and rained us out so we couldn’t play, which wasn’t a bad thing,” Jones said. “If they lose, I feel bad. If I lose, I feel worse. It’s not comfortable because you have such strong feelings about that person, especially with Schloss, knowing him since he was a freshman in college.”

Both went on to the NCAA tournament; Schlossnagle was knocked out in Regionals yet again — Jones made it back to Omaha but lost in the second round.

The next year, TCU moved into the Mountain West conference. In seven seasons, Schlossnagle’s Horned Frogs won the conference championship each time, made the NCAA tournament each year and made two NCAA Super Regionals.

In 2009, just before Schlossnagle’s ninth season as a head coach, TCU hired Chris Del Conte, who now works for Texas in the same role, as its athletic director.

Del Conte and Schlossnagle already knew each other — Schlossnagle’s reputation preceded him. Together in Fort Worth, Del Conte gave Schlossnagle an avenue to life outside of baseball within the university. Every Sunday, for years, the two would walk a three-mile loop around campus.

“We would just talk about our lives, talk about our families, talk about everything but sports. Some days in the game, the game gets so all consuming that you don’t have an outlet to talk about anything else besides the game,” Del Conte said. “Our conversations were nothing about the game. [We talked about] what we wanted for our kids, what we wanted for life. Those are my most cherished memories [with Jim] because the wins and losses are difficult. Long after the game of baseball is over, he’ll be a friend of mine.”

And, in Schlossnagle’s first year working with Del Conte, 10 years after his first appearance, TCU went to the College World Series. Schlossnagle had his taste of college baseball’s mecca exactly a decade before, and here he was again.

He’d studied the game under Jones. He’d learned how to turn impatience into drive. He’d channeled his energy through Del Conte. Now, he had his chance.

“If it’s a positive or a negative, I have the same [impatience]. Being in a program where we had that kind of success, that was something I think he really bought into; I know he did,” Jones said. “That’s something that has carried us always. We didn’t come from losers.”

TCU blew past Florida State in its first game in Omaha, ever. The Horned Frogs then hit a wall against the UCLA Bruins, but redeemed themselves after knocking the Seminoles out of the tournament in Game 3. Matched up against UCLA once again, TCU was sent home.

This 2010 run was instrumental regardless of the shortcoming. A precedent was created.

TCU joined the Big 12 in 2013 and struggled in its conference-christening season, finishing sixth. Schlossnagle was forced into patience for a year after joining the Big 12, but it paid off. In 2014, 2015, 2016 and 2017, Schlossnagle led the Horned Frogs to four College World Series.

They came up short each time. Schlossnagle said, “I think any time that you don’t ultimately finish in the World Series and win the final game, you feel like you’ve …” He paused to find the words.

“I just wanted to be able to see it all through. The toughest one was 2016. We’re in Omaha, we win the first two games, we’re in the driver’s seat,” Schlossnagle said. “We have to win one game to make it to the championship series, and I really felt like we had a national championship team. That one will forever eat at me because I felt like that was our moment. We were right back there in 2017, but ‘16 is the one that will forever haunt me.”

In the three full seasons from 2018 to 2021, TCU was unable to recreate the success from years before, missing the tournament entirely in 2018. Maybe Schlossnagle got complacent. Maybe the weight of the built-up expectations had become too much.

“I think any coach that tastes Omaha wants to win it. He was driven by trying to win a national championship,” Del Conte said. “It doesn’t define him, by any stretch of the imagination. What defines him is the people that he gets to coach every day.”

There is no diagnosis for such shortcomings; only so many excuses can be made. Schlossnagle won’t be the one to make any excuses, though. He owns his failures; he wears them as a reason to do better.

A new chapter

Here we are in 2022. The A&M baseball program is led by Schlossnagle. The implementation of his vision is underway. He’s marked by his past — failures and achievements; wins and losses.

TCU and Schlossnagle were married for 18 years. It was flooded with wins but ended in failures, at least in accordance with his expectations.

Jim and Kami were married for 23 years. It produced achievements, namely their two children, but ended in failure in accordance with Jim’s expectations.

“I’m not married anymore, and that’s a failure. Any time a marriage ends in divorce, that’s an incredibly painful thing. I don’t care how well it goes, it’s awful,” Jim said. “I thought I was a good husband, but I think I definitely could have been a way better husband, and so I’m not a husband anymore — at least not right now.”

All that he left behind is instrumental in what he’s attempting to build. Jim, now 51 years old, has learned; he’s grown. He has the energy and opportunity to rebuild a program again.

“I just felt like I don’t know how long I want to coach. I mean, I know I want to coach another 10 or 15 years, but my point is I’m not sure I want to be a coach at 70,” Jim said.

But, he will be at A&M for the next seven years. This may be his last chance to return to the College World Series and fully realize the goal.

The chase for a national championship need not be spoken. If he had to write it on the board for everyone to see, he would want no part in that program. Instead, he can focus on the details of a national championship’s creation.

“The beauty of coming to a place like Texas A&M is you don’t have to create any [standards]. They’re already in place,” Jim said. “The Core Values of the university, we just have adopted and tried to build on those within the baseball program. All we’ve done is define those from a programmatic standpoint, and those are our standards. I think if every single person in the program lives up to those standards — nobody is going to be perfect — but strives to be the very best in each one of those areas every day, then the goals will take care of themselves.”

Baseball is unpredictable. It’s uncontrollable. To many, that’s what makes the game great. Jim is controlling what he can.

He wants to build a community. He wants his baseball program to be tangible to its fans. He wants to be intentional in everything he does. He hopes the wins will follow, but his No. 1 goal, tempered through experience, is deeper than any trophy.

“You can’t hide out and expect people to buy into the program based on wins and losses. We all know the more you win, the more people will come [to the games], but I think when people feel like they have a personal relationship or they’re involved with the program, then they’re going to want to be a part of the program,” Jim said. “They’re going to ride the ups and downs with you. That’s one of the great things about college baseball. The baseball matters, the relationships matter and it’s our job to be intentional with going out and creating and nurturing those relationships.”

The hard part is not the creation — Jim knows he can do it — it’s the waiting. He’s never been a loser; he doesn’t have time to be.

“He knows himself better than anybody else. His patience level is because he expects the best out of himself and because he expects the best out of everyone around him. It was not a negative trait,” Del Conte said. “I always used to tell him, ‘Coach, don’t change who you are. You’re impatient, but that impatience is your drive. Just know that how you harness your impatience, you’ve got to make sure that you’re in sync with what your message is.’”

Jim’s message is loud and clear:

“I just want an Aggie baseball game to be the greatest experience you can possibly have when you come on this campus.”