“The economy’s not a class you can master in college

To think otherwise is the pretense of knowledge”

— “Fight of the Century: Keynes vs. Hayek Rap Battle, Round Two”

A single sentence — in fact, a single word — in Senator Bernie Sanders’ 2015 summary of his “College for All Act” underscores a central problem with proposals for free college. The single sentence is: “Today, total tuition at public colleges and universities amounts to about $70 billion per year.” The single word is: “today.”

Knowing the total cost of tuition today is simple — merely check this or that spreadsheet. Knowing the total cost of tuition tomorrow is far more complicated and may very well be impossible. Still, Sanders was right to point out that a significant reason otherwise capable students do not attend college is skyrocketing tuition. Where he failed was in considering the logical conclusion of his premise (and the very purpose of his plan), which is that as costs to students go down, enrollment — and the attending cost to the government — goes up.

How much would an increase be? No one knows. Indeed, no one can know, as it would be the result of millions of individual decisions made by high schoolers over the course of a decade. Therefore, only one thing is certain: because the senator extrapolated from the $70 billion figure in determining the ten-year cost of his plan, its $700 billion price tag — two-thirds paid for by the federal government and a third paid for by state governments — was most likely a gross underestimate.

Little has changed since 2015. Two years later, Sanders revamped his “College for All Act,” which now has an estimated cost to the federal government of $48 billion a year. He has also proposed canceling all outstanding student debt for a one-time cost of $1.6 trillion. Again, the latter number is likely accurate (inevitably it came from some spreadsheet somewhere) while the former is inaccurate. In addition, Sanders has held firm to his promise that, going forward, the federal government will take on two-thirds of the total cost of tuition with states picking up the rest.

Let us be clear on this point: many states will refuse to do this (just ask President Obama how his Medicaid expansion went), and states which do acquiesce will add puppet strings to the money they doll out.

Consider New York’s plan for free tuition, which stipulates that students who take part must live in New York for up to four years after graduation. West Virginia has the same requirement but for two years. Kentucky, meanwhile, has limited funding to those subjects which prepare students for jobs their economy has a hard time filling. These are sensible conditions: if states are going to spend billions of dollars educating young adults at public institutions, it is fair to demand a portion of the resulting benefits. Aggies frustrated by the shenanigans in Austin should imagine the ensuing chaos when politicians have a broader claim to our education — and our lives — because they are paying the bills.

Another problem in Sanders’ plan, however, is that it fails to address the root cause of ballooning tuition: degree inflation, or the unnecessary requirement of college degrees for middle-skill jobs.

A 2015 Harvard Business Review survey found that “67% of production supervisor job postings asked for a college degree, while only 16% of employed production supervisors had one.” There are two main reasons for this: First, businesses are increasingly shunting the cost of training employees onto colleges as a way of cutting expenses. Second, companies often use the attainment of a college degree as a heuristic for evaluating an applicant’s intelligence and work ethic. As a result, “[m]any middle-skills jobs synonymous with middle-class lifestyles and upward mobility—such as supervisors, support specialists, sales representatives, inspectors and testers, clerks, and secretaries and administrative assistants—are now considered hard-to-fill.” Congratulations, corporations, you played yourselves — and Sanders.

Degree inflation, as well as the easy money dispensed by governments, necessarily cause tuition increases because they add an incentive to raise costs while removing an incentive to lower them. If Sanders could figure out a way to solve that problem, he would be a true revolutionary. Until then, he is merely taking his cues from the very businesses whose hatred he welcomes.

The Pretense of College

September 24, 2019

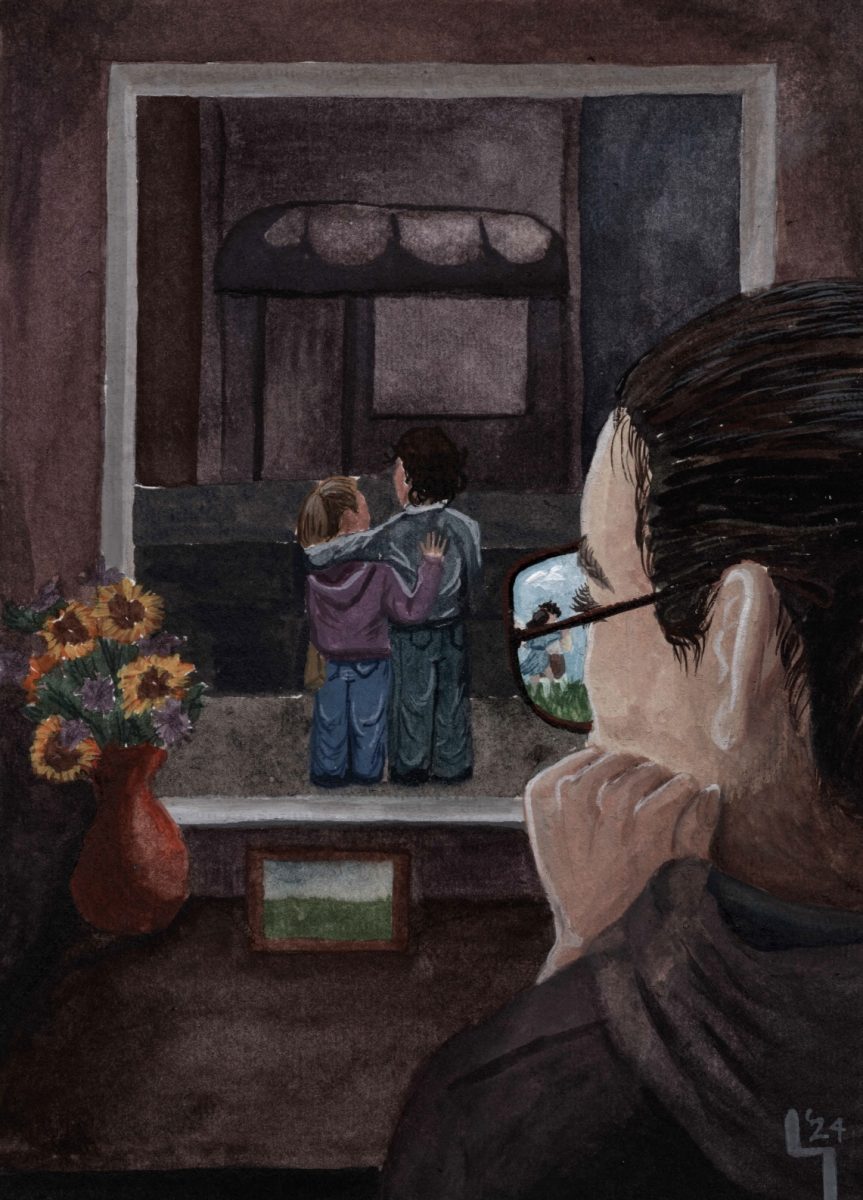

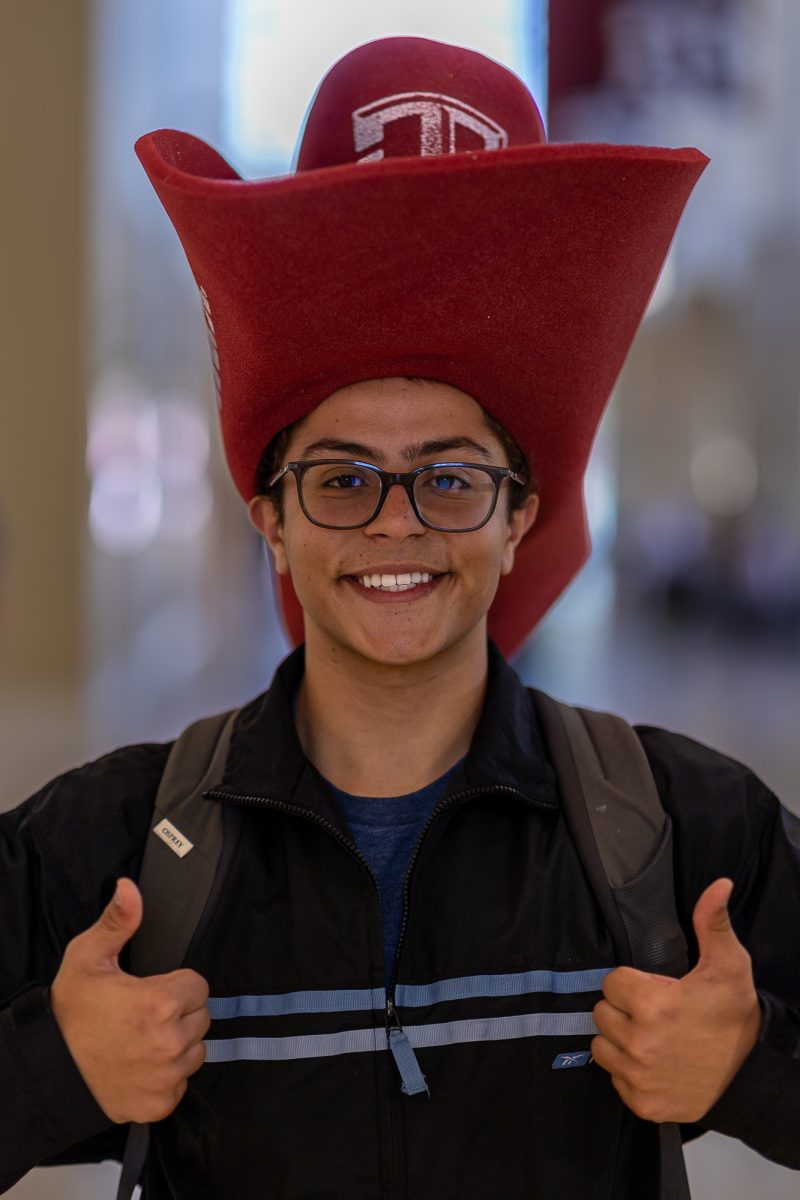

With investments ranging from years of one’s life to thousands of dollars, students have begun wondering whether university is worth it. (David Allen/FILE)

0

Donate to The Battalion

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas A&M University - College Station. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.