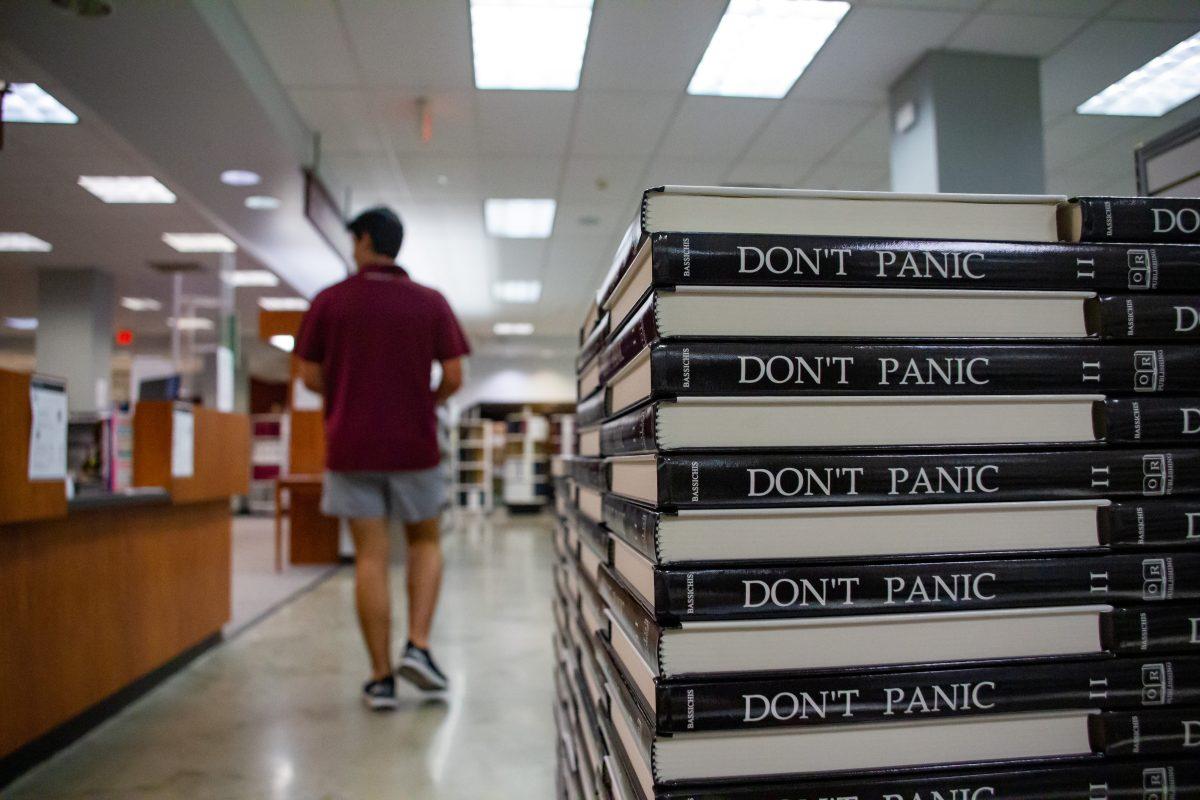

Textbooks are expensive — I think that’s one thing we can all agree on. But is removing their price tags really the key to lessening students’ financial burden?

On Aug. 24, West Texas A&M University announced all textbooks would be provided to students free of charge beginning in fall 2024. Items like access codes, digital materials and reference material won’t be covered, but university funds will pay for any physical textbook costs for the semester.

Before discussing the pros and cons of free textbooks, I want to take a moment to explain how this happened. While we here in College Station have been reeling from the resignation of former President M. Katherine Banks and the ensuing chaos, West Texas A&M, or WT, has been dealing with its own set of controversies.

The new “No-Cost-to-Student” textbook policy was planned and facilitated by WT President Walter Wendler.

“I don’t think I’m the only university president in the United States of America that doesn’t know how many courses require textbooks,” Wendler said in a statement to Inside Higher Ed.

This is probably true. But, he’s absolutely the only one to begin such a bold program without running any of the numbers.

This decision to eliminate textbook costs comes after WT committed to not raising tuition or academic fees until 2025. So, after making an unfounded promise to students without knowing the possible expenses, he is also left without a way to pay for the program if it oversteps whatever budget they gave it.

“We are going to run an experiment basically to see what happens,” Wendler said — which is not exactly the mindset I would like to see in a university president announcing a groundbreaking and costly new program.

The plan was developed, Wendler claims, over several years. It began with an article he wrote called “Textbook-Free, Not Free Textbooks.” If you’re an astute reader, you’ve already noticed that this baseline article and the program he installed are completely contradictory.

Written in 2018, the article extrapolates the possible benefits of Open Educational Resources, or OER, documents created and licensed intentionally to be free for anyone and everyone to use. He claims that OER affords professors complete “academic freedom” because “rather than an editor in New York … determining what the course content should be, the person teaching the course decides exactly what to use.” This argument is entirely irrational, mainly because that isn’t how courses are set up in the first place.

Currently, professors choose which textbooks to use in their classes. In his example, they would choose which OER documents to use. The publishers determine what is published; the professors determine what is taught. The only exception would be if professors wrote their own OER material, but that’s not what he’s talking about here. We’ll get to that later.

That all came from his 2018 article. On Aug. 24 Wendler sent a university-wide email announcing the school’s new “No-Cost-to-Student” textbook policy. This email was the first time either faculty or students had heard of the plan. David Craig, president of WT’s Faculty Senate, says he first heard of the plan in a meeting with Wendler. By the time Craig had returned to his office, “the president’s announcement was in his inbox.”

Don’t worry, it gets worse. In the email, Wendler charged faculty with creating their own open-access materials. That’s right — after getting basically no input from faculty, he wants them to invest incredible amounts of time in creating their own materials. The email claims that deans have already begun this process.

This comes after Wendler claimed in the 2018 article that OER had everything the professors needed and more. To defend its allegedly limitless power, he Googled a single broad term — “the War of 1812” — and showed how many free materials were available. Using his unscientific method, 47 million results were narrowed down into 10,000 allegedly usable articles.

While this may be true for some entry-level courses, very few upper-level classes are going to have the same success. The myriad results will not be present for any professor whose needs are more specific — say, for example, “morphing wings,” a technique studied in aerospace engineering classes. If we follow the same arbitrary steps used in his article, we’re left with a measly 7 articles. The odds of any professor who needs specific, high-level material finding the appropriate documents via OER are slim to none.

Wendler also wrote, with full seriousness, the following in his announcement email; “Traditional textbooks have outlived their usefulness.” This baseless claim came completely out of left field. As a student who underlines, highlights and sometimes even takes notes in my textbooks, I wholeheartedly disagree with this statement. Did Wendler even ask students if they would agree with his statement?

But don’t just take my word for it. He discredits his own point later in the same email with a statement that WT would be raising the student printing allocations from 1500 to 3000 pages so that OER documents could be printed out … thus creating a traditional textbook.

Needless to say, WT faculty is not incredibly pleased with this development. As of Aug. 29, the announcement email was the only information about the plan that faculty and the WT Faculty Senate had.

“There’s just a vast host of issues that this doesn’t address in any detail at all,” Craig said.

To close this look at the chaos currently plaguing WT, I’d like to bring one last Wendler quote into the discussion.

“[The plan] is challenging … but I think we should give it a good try and see what happens … And my guess is we’re going to be surprised.”

Oh, I think he’s going to be surprised, all right.

We’ll see how it plays out for WT. What can we expect if the same policy is implemented here?

If there’s one thing Wendler is correct about, it’s that textbooks are disproportionately expensive. Over the past 10 years, textbook costs have risen about four times faster than inflation. Currently, the average price for a semester of textbooks is about $1200. While OER would help a bit with those costs, a large part of student expenditure comes from digital access codes rather than textbooks — remember that digital materials aren’t covered under Wendler’s program.

Why are textbooks so expensive in the first place? Textbook publishers have a monopoly on the market. They can charge whatever they want for print books and still make biannual bank on access codes that expire once the semester ends.

Here’s the concern: if professors stop using material textbooks, some of those publishers will go out of business, creating an even smaller market and even higher markups from the companies that remain. If OER is to completely replace material textbooks, it would have to be implemented on a large scale and with the understanding that the problem could be exacerbated rather than ameliorated.

Wendler’s commitment to lowering student costs is commendable, but this immediate, almost knee-jerk reaction to provide free stuff to students is not the answer. Textbooks are a comparatively negligible amount of tuition costs for students. If lower costs are what Wendler wants, he should be focusing on the bigger picture — tuition and academic fees — rather than treating the symptom.

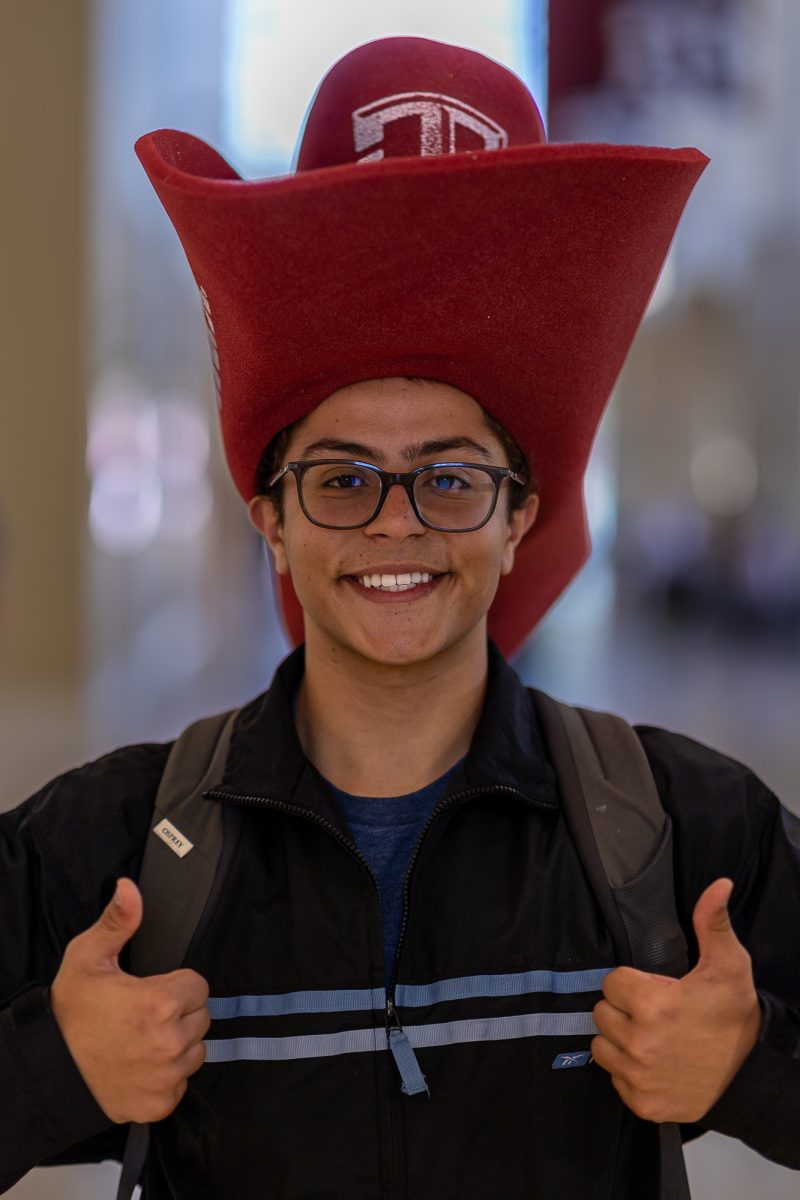

Charis Adkins is an English junior and opinion columnist for The Battalion.