“Drawn-out legal battles can constitute repression if authorities use them as tools of discouragement.” — Andrew Vaserfier, “Lesbian Gay and Student Mobilization at Texas A&M University.”

Though the topic may be tedious, a word should be spared for the technicalities on which Gay Student Services v. Texas A&M would be decided.

On Nov. 29, 1976, Koldus officially denied GSS’s application. His letter (addressed to Michael Garrett and Alternative) should be read in full:

“The request to recognize the student organization called ‘Gay Student Services’ was forwarded to my office for action. I have read and studied the request and, on the basis of the information presented, am denying the group official recognition.

Contained within the Texas A&M University regulations 1975-1976 is the following statement: ‘Student organizations may be officially recognized when formed for purposes which are consistent with the philosophy and goals that have been developed for the creation and existence of Texas A&M University.’ Homosexual conduct is illegal in Texas, and therefore, it would be most inappropriate for a state institution officially to support a student organization which is likely to incite, promote and result in acts contrary to and in violation of the Penal Code of the State of Texas.

Furthermore, the university administrative staff and faculty are responsible for providing referral services, educational information, appropriate speakers for classes and a forum for the interchange of ideas. Student organizations do not have the educational experience, the responsibility nor the authority to educate the larger public. The responsibility for the education of the students at Texas A&M University resides by law with the university administrative staff and faculty.

It is my contention, therefore, that the stated purposes and goals of ‘Gay Student Services’ are not consistent with the philosophy and goals that have been developed for the creation and existence of Texas A&M University.”

The letter is noteworthy for several reasons.

First, it was addressed to Alternative, not Gay Student Services. And when the name Gay Student Services does appear, it does so exclusively within quotation marks — a clear sign of disrespect.

Second, the letter claimed that GSS’s application had been “forwarded to [Koldus’] office for action.” At best, this was a deceptive use of passive voice. At worst, it was a lie. As Koldus himself had already said in The Battalion on Oct. 12, 1976: “Since I disagree with a gay liberation group receiving recognition, I asked that this particular application come directly to me instead of to the Student Organizations Board.”

Third, Koldus had previously told the group that the general counsel would wait until the courts had decided Gay Lib v. University of Missouri. But the letter was issued a full seven months before the case would be resolved.

Fourth, the letter’s bureaucratic nature made one thing clear: A&M would be giving GSS no quarter and would be brooking no compromise.

So GSS did the only thing they could do: they filed a lawsuit. They wanted four things:

- For the court to compel A&M to recognize GSS as a student organization.

- For the court to declare A&M’s refusal to grant their application as unconstitutional — a denial of their First Amendment rights to speech and assembly.

- For A&M to pay damages to GSS for the deprivation of their rights of speech and assembly.

- For A&M to pay GSS’s attorney fees.

In response, A&M filed a motion to dismiss, essentially alleging that even if everything GSS claimed were true, it wouldn’t be enough to rule in GSS’s favor. Two arguments for dismissal stand out.

The first was that GSS did not have standing to sue the university.

The second was that GSS was suing Jack Williams, John Koldus, W.C. Freeman (then-Executive Vice President for Administration) and the Board of Regents in their official capacities as members of a state agency. However, a corner of The Civil Rights Act of 1871 — known as the Civil Action for Deprivation of Rights — was understood to forbid such lawsuits.

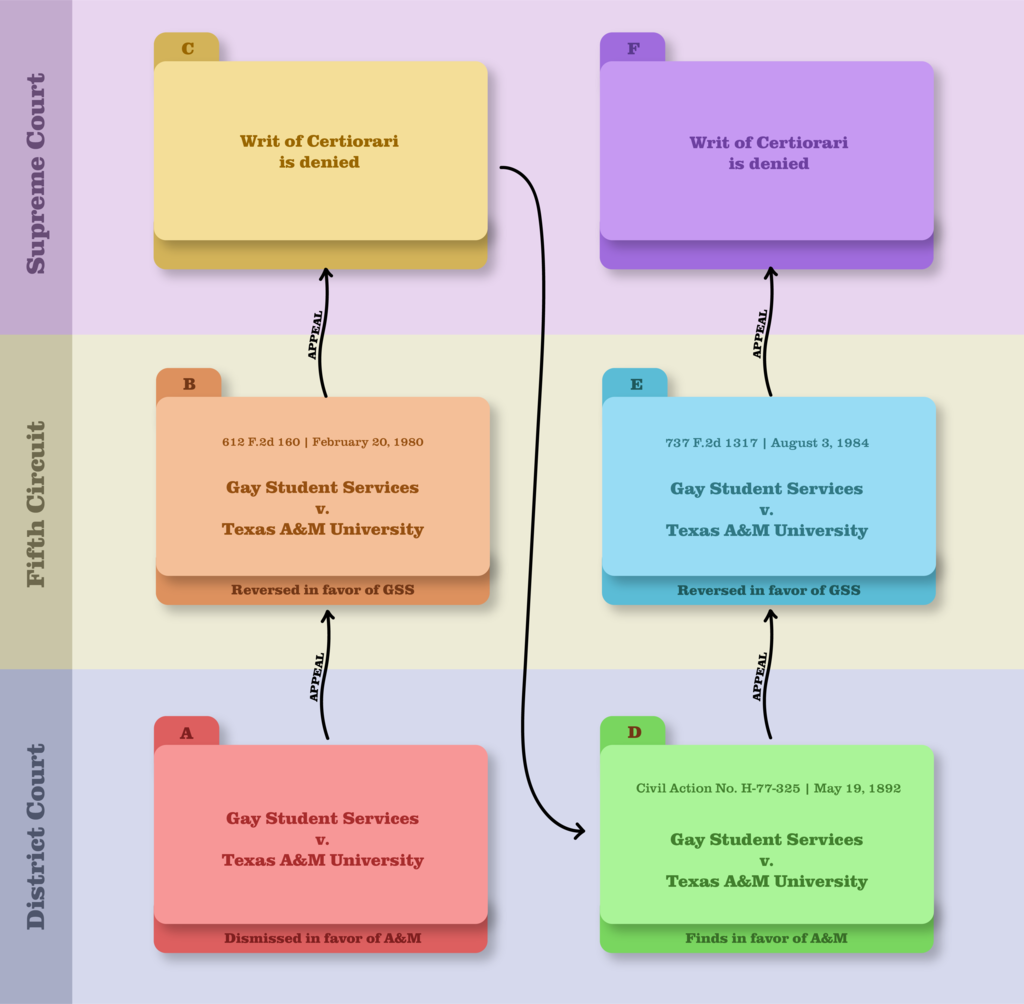

In a rare move, the district court granted A&M’s motion to dismiss without describing their reasoning for doing so. In response, GSS appealed the dismissal to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals.

With respect to the issue of standing, the Fifth Circuit merely wrote: “The assertion that plaintiffs lack standing to bring the suit is frivolous.”

Concerning The 1871 Civil Rights Act, GSS simply lucked out: When the District Court had decided the case, it was true that A&M officials could not be sued for their decision. However, in the time between the District Court’s dismissal and the Fifth Circuit’s ruling, the Supreme Court had reversed this practice.

Here is where things get complicated.

Ultimately, the Fifth Circuit decided to kick back the decision to the district court, and that’s precisely what should have happened. But then A&M appealed the reversal of the dismissal. Instead of getting kicked down to the District Court immediately, it got kicked up to the Supreme Court. Only after the Supreme Court declined to hear the case did the issue wind up back where it started: in the original District Court. Except now, Gay Student Services v. Texas A&M would finally be decided on its merits — namely whether or not it was constitutional for A&M to deny GSS recognition.

(I’ve got a story for you, Ags…

As part of the suit, GSS was allowed to issue interrogatories — questions the defendant is required to answer under oath. This process exists to establish basic facts of the case as well as to preview what information is likely to be the focus of the trial. GSS issued 135 questions to Koldus specifically. Most were relatively straightforward, such as whether or not “any student group ha[d] followed the same procedures in applying for recognition as has G.S.S.”

But GSS also asked such personal questions as whether Koldus had ever had a homosexual experience or whether he had ever attended a gay bar before. If he had, he was asked to describe those experiences. As one might expect, Koldus objected to answering such questions on the basis of relevance.)

If the GSS and its lawyers hadn’t previously understood what they were up against, they surely understood now.

A&M had stiffened its resolve since Jack Williams’ memo. No longer would the school passively leave GSS unrecognized “until and unless [they were] ordered by higher authority to do so.” To the contrary, on March 22, 1977, the Board of Regents had approved the following policy position:

“So called ‘gay’ activities run diabolically counter to the traditions and standards of Texas A&M University, and the Board of Regents is determined to defend the suit filed against it by three students seeking ‘gay’ recognition and, if necessary, to proceed in every legal way to prohibit any group with such goals from organizing and operating on this or any other campus for which this Board is responsible.”

It would be a position to which the school would adhere for the next eight years.