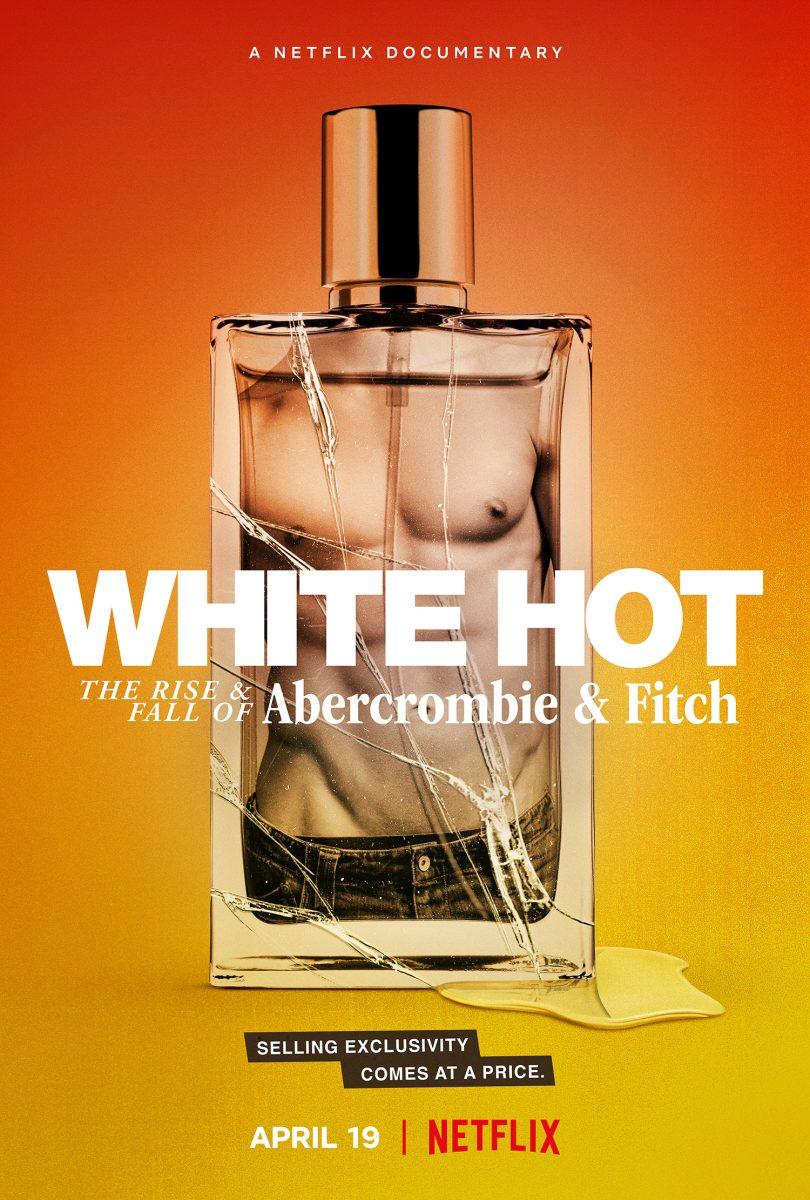

Netflix’s recent documentary “Hot White: The Rise & Fall of Abercrombie & Fitch,” directed by Alison Klayman, details the process that led to the success of the controversial clothing company, as well as the under-the-table tactics used, which eventually ran the company to its inevitable plummet of disgrace.

The documentary opens with the beginnings of Abercrombie & Fitch, as well as the already known controversy with the brand, including the distinct niche audience it targeted, contrasted by the immense demand by every American student ranging from middle school pre-pubescents to young adults in college. The documentary then begins to unravel the tainted morality of its iron grip influence across the youth groups, especially upon those whom the brand excluded in its marketing strategy.

The documentary states that “what it sells is aspirational,” meaning the brand didn’t just sell the clothes, but also the idea of becoming the model, the standard and the influence among your peers. The interviewees on the documentary made note of the power of exclusivity, and explained how the brand was made so distinct when they were in school because they were not wearing it, but others were. Upon a superficial glance, this exclusivity is a typical coming of age struggle that every teenager faces, but the documentary starts to show that this exclusiveness was not just set up, but intentionally manufactured upon the company.

Mike Jeffries, former CEO, had the vision of a model of Abercrombie & Fitch which, as the documentary describes it, combined the heritage of the sophisticated outdoorsman brand it was with the exclusivity, elitism and sexual appeal that catered so well to the young demographic of the time. Paired with photographer Bruce Weber, Jeffries’ execution of the Abercrombie & Fitch brand came to fruition, with the look focusing on the aesthetic of the rich, the white and the fit. As Robin Givhan states in the documentary, “The goal is not to get people what they are asking for, but to make them ask what you’re offering.”

Even with the moral disdain of pitting body dysmorphia upon the consumer, Abercrombie & Fitch involved itself in unethical job practices, mainly on its policy of only hiring attractive people. This requirement doesn’t seem so harsh until it is considered that the defining quality of attractiveness that Abercrombie & Fitch looked for was white and thin. Journalist Moe Tkacik reported on this practice for the Wall Street Journal, later finding out from an Abercrombie & Fitch manager, “You have to rank all your employees on a scale of ‘cool’ to ‘rocks’ and if they aren’t at least ‘cool,’ then you have to zero them out off the schedule. It didn’t matter what your sales were, all that mattered was that the employees that you took pictures of and sent back to headquarters were hot. Clearly this is illegal, right?”

Former store employee Carla Barrientos, a Black woman, described her experience struggling with working hours and being given only night shift positions, only to be fired once she brought it up. Former Asian store employee Jennifer Sheahan recounted how the chain she worked at let go a majority of the employees after someone from corporate found that the majority of the people working there were Asian American. Former Filipino store employee Anthony Ocampo tried to rejoin as an employee of the store, only to be told by one of the employees, “My manager said we can’t rehire you because we already have too many Filipinos working at this store.”

This only scratches the surface of the many practices Abercrombie & Fitch have been shown to do in the documentary. The documentary gives insight into the power that is granted with influence and publicity, where exclusivity reigns supreme in a world where identity is always questioned. The vision Abercrombie & Fitch wanted wasn’t on par with the reality of what America is, yet so many bought into it just for the sake of being one with the crowd. The meticulous amount of dedication Mike Jeffries had, from buff torsos on shopping bags to who gets to work day shift due to a factor of genetic lottery, should make us question who we are as individuals and as a whole.

Abercrombie & Fitch is now run by a new CEO, Fran Horowitz, since Feb. 1, 2017, with remarkable changes happening across the company. A sense of inclusivity and realism is reflected upon the image now, focusing more upon the actual clothes being fitted on models of all shapes and colors, no longer fetishizing preppy white men and women running half-naked on selectively inclusive areas of the country. Whether or not Abercrombie & Fitch will succeed with this new outlook is up to the shoppers — and their deliriously expensive clothing — and it is nice to see a brand learn from its mistakes and seek better outlooks, but it would be a lie to say that the imprint of exclusivity culture the brand has left behind will be swept under the rug.

Ruben Hernandez is a journalism junior and art critic for The Battalion.