World War I, World War II, the Vietnam War and over a century of military history rest in solemn stillness, encased in a metal warehouse just off Highway 6 at the Museum of the American G.I., where echoes of battles fought long ago are brought back to life.

Tanks, artillery and uniforms preserved in pristine condition stand as silent guardians of the past. But here, history doesn’t just sit behind glass — it roars to action. Engines rumble, cannons thunder and the past is not just remembered but felt.

Executive Director Leisha Mullins, alongside her beloved corgi guide dog named Annie, passionately tells these veterans’ stories — not just through words but rather the very uniforms they wore, the weapons they carried and the vehicles they operated.

Annie, with her short legs and loyal demeanor, has become somewhat of a mascot that adds a touch of warmth to the museum’s atmosphere. Each piece of history at the Museum of the American G.I. is a reminder of the bravery and sacrifice of those who fought.

“The vehicles are the hook,” Mullins said. “They draw people in, but once they’re here, they become captivated by the deeper history behind each exhibit.”

College Station native Corbin Olson, a lifelong visitor of the museum, said his family regularly embarks on road trips across the country to explore museums. He regards the American G.I. as his favorite and especially appreciates the wide range of displays, an aspect that captivated him as a child and made each visit a unique and enriching experience.

“Seeing all these pieces of history was something I will never forget,” Olson said. “I have never been to a museum that was more alive.”

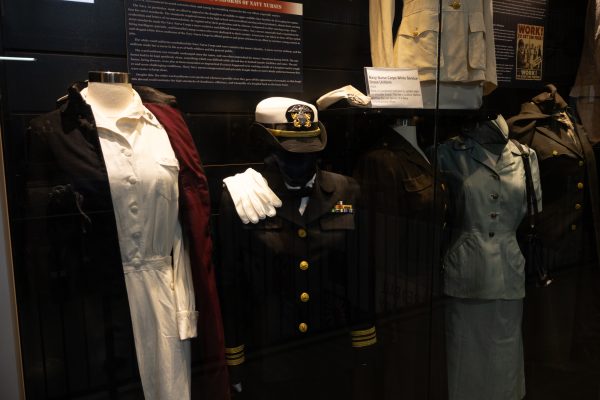

Among the museum’s most treasured pieces are the uniforms that proudly display the legacy of those who served. From white and blue World War I uniforms to neatly-kept fatigues from the Vietnam War, the attention to preservation is remarkable, with garments in such good condition that not a single thread hangs loose.

A notable uniform display belonged to Capt. Robert Acklen, Class of 1963. His uniform stands as a tribute to the men and women from Texas A&M who have served their country. Nearby is a U.S. Air Force F-86 fighter pilot flight suit worn by Lieutenant William R. Stade, Class of 1964. His suit, with its vintage patches and worn edges, captures the look of fighter pilots during the Korean War Era, a significant part of military aviation history.

One of the most poignant areas is the Texas Vietnam Heroes Exhibit, where an array of dog tags solemnly represent 3,417 Texan soldiers who gave their lives in the Vietnam War. Among them, 102 black dog tags symbolize the Texans missing in action, serving as a haunting reminder of those whose fates remain unknown. Mullins said the exhibit underscores a powerful message: No man left behind.

“It’s not all about driving a tank or flying an airplane,” Mullins said. “There is a sacrifice involved with all of our veterans,” Mullins said. “They’re willing to give their life for service to our country, and we need to be able to honor them by telling their stories and what they have done.”

The museum’s collection is built on donations from families of veterans and often employs students eager to help preserve this living history.

Maritime archeology and conservation graduate student Tyler McStravick said he worked at the museum for about two months through a work-study program. After visiting as a student, he said he was struck by the museum’s significance and thought it was one of the best attractions in the Bryan-College Station area.

“We have all these armored vehicles here, and they all run,” McStravick said. “It’s pretty amazing. This museum gives everyone a better idea of the experience of people who served and what they went through.”

Exhibits rotate every so often, with vehicles moving from inside the building to the gravel path for “History in Motion” and “Living History” exhibits. Volunteers gather monthly to learn how to operate the vehicles. Mullins said it’s not just about popping in and driving a tank — there’s a process to operate them, and it requires careful training to ensure safety.

University studies senior Zachary Hashey, a volunteer who gravitated toward the museum to get the behind-the-scenes experience of operating the vehicle, said he assisted visitors during events and helped them get on and off the machines of war. Hashey said he saw visitors light up when they saw the tanks revive during the “History in Motion” events.

“There’s nothing that compares to seeing a tank fire, the static and the intricate details in real life,” Hashey said. “I think the museum does a really great job with “History in Motion,” and it really does give people a sense of scale of what it felt like to see the tanks in the battlefield.”

The performance and overall appearance of vehicles such as the Ford GPA ‘Seep,’ River Mark II Patrol Boat, M18 Hellcat tank and AH-1F Cobra helicopter stand as testament to the detailed restoration work performed by the museum.

“None of these vehicles looked how they look now when we got them,” Mullins said. “We do a ground-up restoration and disassemble and strip everything out of the hull, and then we sandblast it and repair it.”

Mullins said the World War I-era French Renault FT-17 tank displayed in the museum was provided by a family who could not repair it by themselves. During that time, the museum cultivated a relationship with a group in England that had two variations of the tank. Through a combination of luck, finding parts in flea markets and working with others, staff were able to fully restore the tank.Mullins said restoration projects are often a collaborative effort, requiring both creativity and resourcefulness to turn a relic in need of repair into history.

“My favorite restoration was the ‘Tar Heel,’ an M3 gun motor carriage,” Mullins said. “It’s a very rare vehicle, and that particular one was a special restoration project.”

Why was it special? Mullins said a Marine Corps veteran, Ed Eyre, approached the museum after his wife passed away and asked them to restore the Tar Heel. One of Eyre’s buddies had driven that configuration of the vehicle, and he wanted to honor his friend’s memory by painting it similarly.

“The first time we showed it in action, Ed and his buddy drove it,” Mullins said. “They had the biggest smiles on their faces because they took a time in their life, which was the horrific fighting, and turned it into a positive experience of presenting that vehicle.”

Mullins said the museum’s commitment to preserving military history, whether through restoring a rare M3 gun motor carriage or honoring Texas soldiers in the Vietnam Heroes Exhibit, keeps the memory of veterans alive. To her, it’s not just about the machinery or the battles fought — it’s about the people behind the uniforms, the sacrifices made and the legacy they left behind.

“It’s the stories, and it’s the people that are the important thing,” Mullins said. “You can’t evaluate historical events in current modern lenses. You have to learn from your past.”