Texas A&M will become one of three universities in the United States with rocket testing capabilities once the construction of the Propulsion and Energetics Research Laboratory, or PERL, is complete.

The lab will test rockets and other projects in extreme conditions, beginning with the Macaw Thruster, an engine commissioned by the Department of Defense and other private contractors for satellite use.

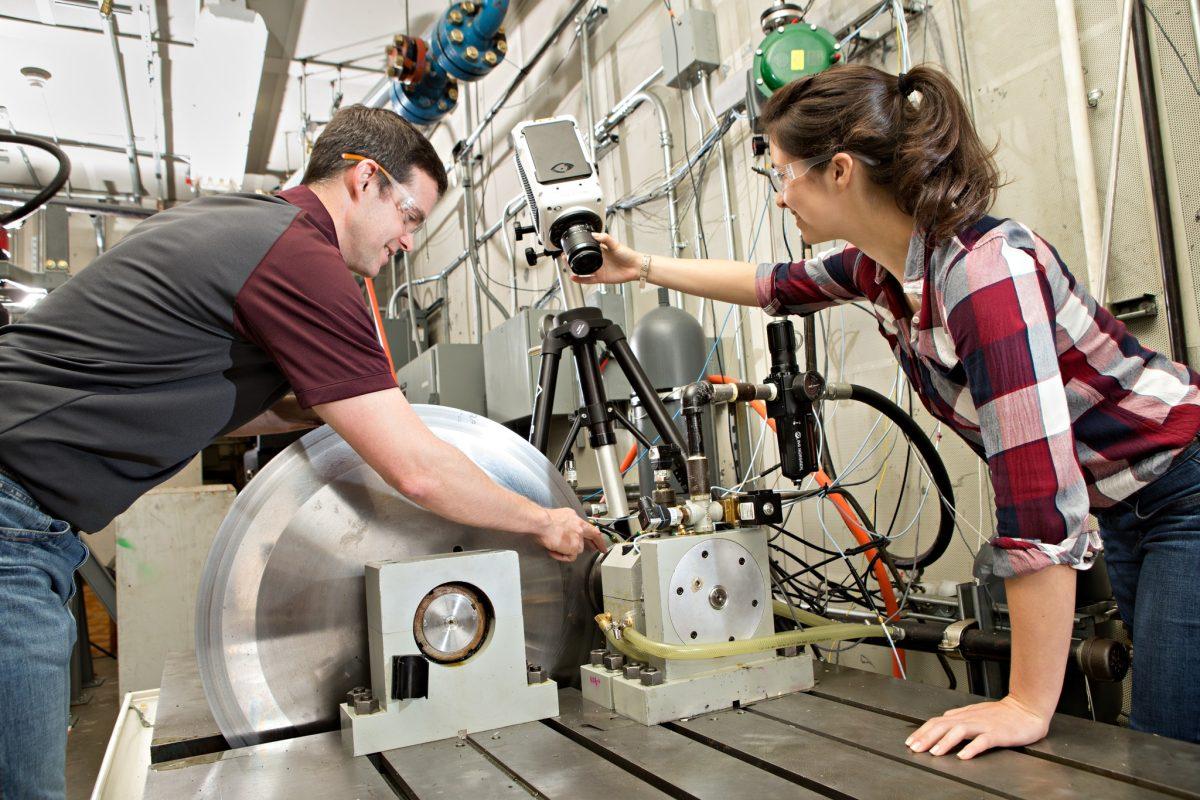

The director of the facility, Chris Thomas, Ph.D., said the laboratory’s purpose is to provide a safe operations space for testing potentially dangerous areas of interest — such as rockets.

“What it really is, is a facility to come and do extreme condition testing,” Thomas said. “It’s [for extreme conditions], by which I mean high pressure, high temperature [and] high flow rate. Things that are dangerous to do are perfect to do in there in a safe manner.”

While the building itself does not host any groundbreaking technology, it is designed to streamline testing and provide experimenters the ability to run more dangerous experiments than a normal lab could manage, Thomas said.

“We can drop it in this building that has seven blast-proof cells, and the idea is you can do all these things and if something goes wrong … that everyone is perfectly safe,” Thomas said.

Thomas said one of the laboratory’s first projects is the Macaw Thruster. The Macaw Thruster, along with its companion monopropellant ASCENT, is designed for the U.S. Air Force to use to maneuver satellites in orbit.

“We use [ASCENT and the Macaw Thruster] to move satellites out of harm’s way, of either something like a micro-meteoroid or an actual military threat,” Thomas said. “Some of the future of warfare will be fought in space, taking down people’s satellites.”

The Director of Advanced Propellants Michael Martin, Ph.D., said the new chemical propellant that will power the Macaw Thruster, ASCENT, is being developed by researchers at the nearby Turbomachinery Lab and the company Benchmark Space Systems to replace the predominant propellant — hydrazine — due to both the efficiency of ASCENT and improved safety.

“That’s one of the really nice things about [ASCENT,] is that most rocket fuels, if you have any kind of leak, it kills you pretty quickly, within a minute,” Martin said.

Martin said ASCENT was designed to replace hydrazine because hydrazine’s hazardous nature requires extensive safety precautions, halting research, Martin said.

“Hydrazine will burn your lungs and kill you rather quickly, whereas [ASCENT] … you can have it out on the table, open …,” Martin said. “As long as you don’t drink it, you’ll be fine.”

Martin also said the new thruster and propellant could be used in a potential global conflict, citing its improved efficiency of thrust and safety in comparison to the currently used hydrazine.

“We know in the first days of World War III that the [communication] satellites might get destroyed by laser or by whatever,” Martin said. “And so, you could have replacement satellites already built and in a warehouse … you can’t do that with hydrazine.”

Martin said while this new technology is promising, it will likely take years to be implemented due to the difficulty of replacing a propellant that the U.S. government has been using for decades.

“It hasn’t flown for 40 years like hydrazine has,” Martin said. “That’s the problem with trying to introduce new things.”