In October 1893, a group of Texas A&M cadets picked up their pens and produced the first edition of a 125-year legacy on the A&M campus.

The Battalion, Texas’ longest continuous college publication, celebrates 125 years of service to Texas A&M University in the 2018-19 school year.

The Battalion, Volume 1, Number 1, debuted on Oct. 1, 1893 as a student publication produced by the Austin and Calliopean Literary Societies, the two most well-established organizations on the campus at the time.

The first editor-in-chief was Ernest L. Bruce, Class of 1894 and a civil engineering grad who would go on to attend the University of Texas Law School, serve as a district judge, county attorney and state legislator. In the first issue, Bruce called upon his fellow cadets to write something for every issue.

Humble beginnings

The Battalion descended from two successive literary magazines published by the literary societies.

In 1878, two years after the College was established, the literary societies began a monthly publication called The Texas Collegian. Its name was changed to The College Journal in 1889. The College Journal was a literary magazine containing small excerpts of student’s news and views, according to “A Centennial History of Texas A&M University” by Henry Dethloff. The College Journal was published until 1893.

When The Battalion replaced The College Journal, it used more of a newspaper format but held onto its literary roots for many years.

The Battalion was published monthly until 1903 when it became a weekly publication. It first appeared in newspaper form on Oct. 8, 1904.

Another change was made in 1904 when the Austin and Calliopean Literary Societies turned the paper over to the Association of Students. After this, The Battalion lost much of its literary magazine character.

Trouble begins to brew

As The Battalion gained influence as a weekly newspaper, a storm was gathering on the A&M campus in 1908. Students were becoming discontent with then A&M President Henry Hill Harrington.

In the April 22 issue of The Battalion, an article appeared that disputed a statement made by President Harrington that recent turmoil on the campus had been forgotten and things were returning to normal.

On May 20, 1908, the Board of Directors issued instructions to the president to maintain order on campus. They said recent articles that had appeared in The Battalion were disrupting the campus and the responsible parties should be punished.

As a result, seven junior class Battalion editors were suspended from the College and the head of the English department was ordered to censor future Battalions in accordance with a rule long in effect but seldom enforced. This was only one of many incidents on the campus that came to be known as the A&M College Trouble of 1908.

A staple of Aggieland

The Battalion also listed two women as society reporters on the staff in 1910, Miss Esther and Francis Davis. It is not known whether they were daughters of professors or women from the Bryan-College Station community.

By 1916, The Battalion had firmly established itself on the campus and boasted “the largest college circulation in the South,” according to “The Battalion: Seventy Years of Student Publications at the A&M College of Texas” by Vick Lindley.

As the 1920s roared by, students continued to publish The Battalion. In 1928, the paper was under the supervision of a Student Activities Committee, which functioned as an advisory board.

The Faculty Publications Committee was formed in 1929 to supervise the functioning of the staffs. However, all work on the paper was done by the students with no censorship. The editor and business manager of The Battalion were elected by popular vote of the student body at the end of each school year.

A typographical error

In the 1920s, a typographical error caused a mix up in the volume numbers. From Volume 30, The Battalion jumped back to Volume 21. The mistake was never corrected, but since The Battalion no longer includes volume numbers, it’s not a problem for current editions.

In 1930, The Battalion began publishing a monthly humor magazine. Filled with jokes, poems and humorous stories, the magazine originally was substituted once a month for one of The Battalion’s weekly issues.

The Battalion magazine was suspended “for the duration” because of paper shortage and a lack of Corps of Cadets as a result of World War II. The last magazine was published in 1943.

In 1931, the A&M Student Publications Board was created to handle the administrative details of all student publications. The board was composed of the four editors of student publications (The Battalion, the Longhorn Yearbook, the Technoscope and the Texas Aggie Countryman), two students and three faculty members.

The A&M Press began to print The Battalion in 1931. Before that, the paper had been printed in Bryan. For the first time, The Battalion was provided with its own campus office.

The newspaper’s influence continued to grow as it expanded into a three-times-a-week publication during the 1939-40 school year. The Battalion became the official publication for the College and for the city of College Station, according to Lindley’s book.

In 1941, the Student Publications Board and the Student Activities Committee combined to form the Student Life Committee. Supervision and control of student publications was assigned to the Student Activities Office.

The second World War

While World War II was being fought overseas during the 1941-42 school year, the Student Activities Office voted to continue the regular publication schedule of The Battalion throughout the summer months while the College was on its wartime, streamlined plan of operation.

As World War II called many of the cadets into service, Battalion space was turned over to these armed service groups who produced their own columns.

“We had stories on A&M men in action,” said Tom Journeay, spring 1941 managing editor of The Battalion. “We were all cognizant of it. Nearly everyone was in the Corps. They realized they were going into the military.”

At this time, The Battalion office was located in the basement of the Administration Building.

By 1945, The Battalion was forced to return to weekly publication because of war restrictions on materials. By the spring of 1947, The Battalion went back to being a twice-a-week publication and later a three-times-a-week publication.

Although The Battalion operated under the Student Activities Committee, it’s preparation, editing, censorship and management were left entirely to the students in charge.

By 1947, enrollment had drastically increased at A&M. It was also the beginning of non-military students on campus. This was a result of World War II veterans returning to campus who did not want to be in the Corps.

The Battalion covered issues such as the increasing enrollment and the purchase of Fish Field, said Richard Alterman, summer 1947 managing editor of The Battalion. Alterman said he remembers The Battalion newsroom as a place for the staff to spend their extra time.

“The Battalion was strictly voluntary,” he said. “We had no journalism classes. It was extra curriculum.”

The summer of 1947 was filled with preparations for eventual daily publication. An Associated Press wire-service teletype was installed in the new offices of The Battalion in Goodwin Hall.

“When Aggies returned from their summer vacation, a daily Battalion was waiting for them in Batt boxes in dormitory halls,” according to Lindley’s book.

The Battalion also became an associate member of the Associated Press and was rated “All-American” by the Associated Collegiate Press.

Although the journalism department had been established at A&M by 1950, The Battalion still operated independently.

“Student publications were quite separate from journalism,” said John Whitmore, editor of The Battalion in the school year of 1951-52. “Those on the staff were not necessarily journalism majors.”

Although they might have found themselves at odds with the administration, Battalion editors were allowed the freedom to direct the paper and its policies.

“Part of our editorial philosophy was to raise hell and stay this side of being burned up, and not in effigy,” Whitmore said.

Making the news

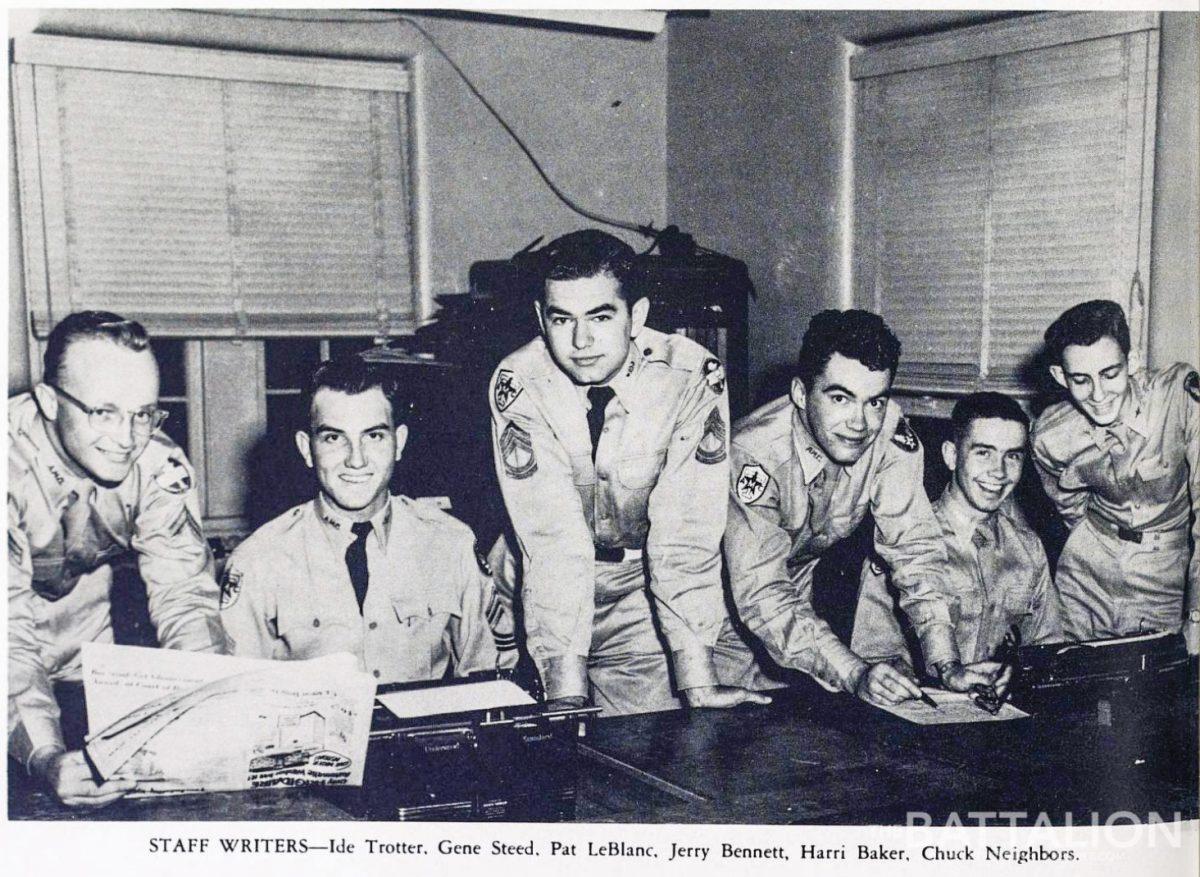

The Battalion itself was in the headlines in 1954 with the mass resignation of the staff. On Feb. 23, 1954, co-editors Jerry Bennett and Ed Holder resigned after the Student Life Committee established an editorial board for The Battalion, “arguing that the student editorial staff needed assistance and guidance,” according to Dethloff’s book.

“Censorship is hidden with advice and assistance,” said Bennett and Holder in a statement to the press following their resignation. “To us, it still means the same thing. This committee has been set up to stop The Battalion from printing the truth about things at A&M which are embarrassing to some individuals.”

The following day, the entire news staff with the exception of a few staff writers, resigned on the grounds that the administration was attempting to censor the newspaper because it had been critical of past administrations.

On March 23, 1954, a new staff was named. Several of the staff who had resigned in February assumed new staff positions in March. One of those was Harri Baker, a former campus editor who took over the position of co-editor with Bob Boriskie, a former sports editor.

“The resignation was an effective device,” Baker said. “I and Bob Boriski, with the agreement of the entire staff, assumed editorial positions. There was no hint of censorship after that.”

During Baker’s time at The Battalion, discussions were underway about ideas that eventually would become significant changes on the A&M campus. The role of the Corps and the admittance of women to the College were two of the issues being discussed at the time. “The Battalion, in those days, was on the side of change, which created controversy,” Baker said. “It was a collective group on the staff. We felt we should maintain and respect the traditions but also encourage change.”

Seeing the future

In 1954, The Battalion was being published four times a week during the fall and spring terms and two times a week during examinations, vacation periods and summer terms.

By 1955, the Student Publications Board had become responsible for establishing the general policies concerning student publications. The board was also responsible for choosing the editor of the paper.

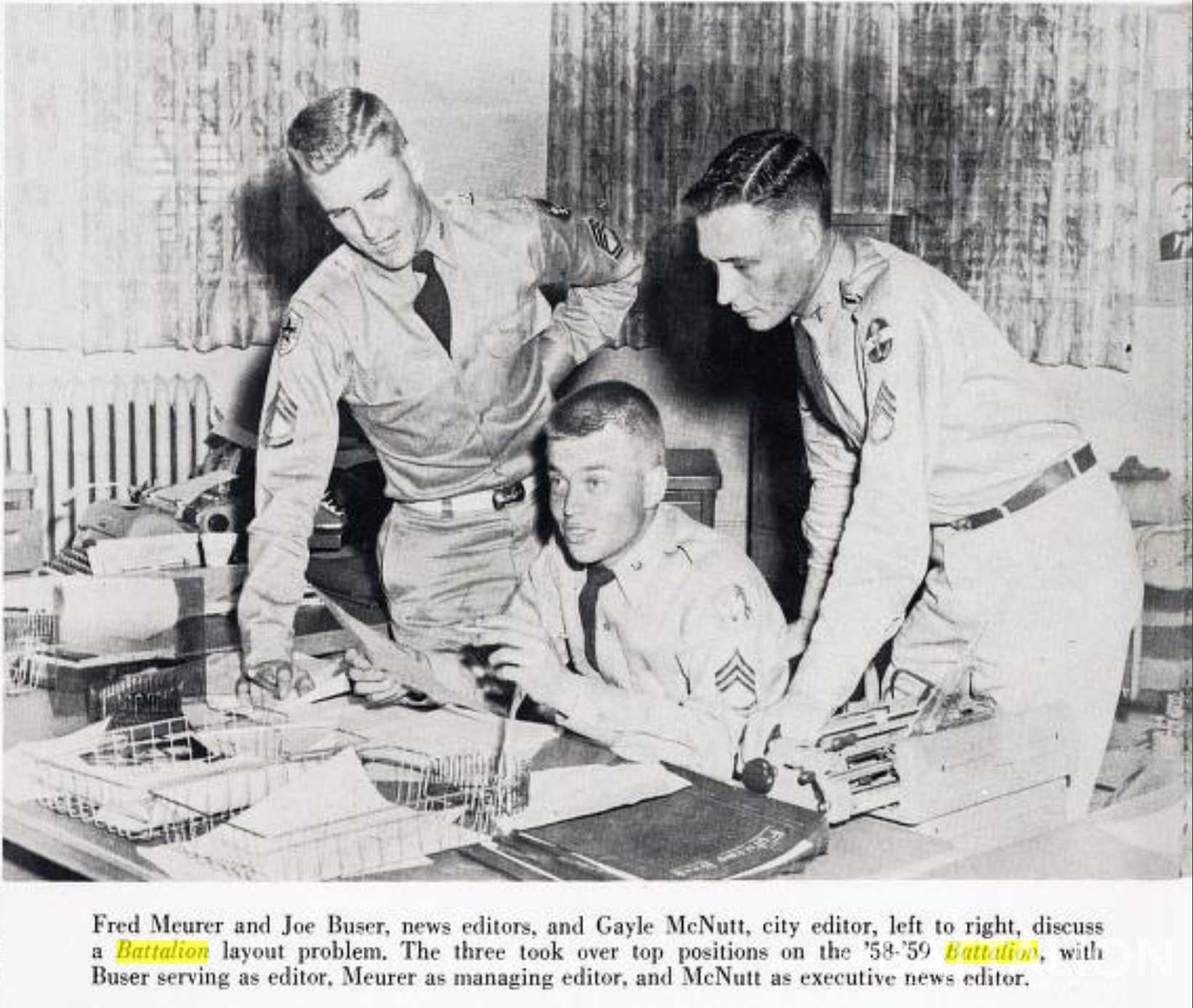

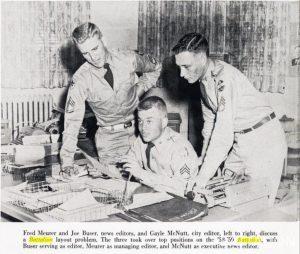

“Being editor of The Battalion was a highly prized campus job,” said Joe Buser, editor of The Battalion in 1958-59. “The editor was just as well known as the Corps Commander. The editor was known by most students and faculty.”

At the time, the College was preparing itself for the 21st century, Buser said. J. Earl Rudder, who was to become the A&M president in 1959, had just come to A&M in 1958 and took over the duties of vice president.

Rudder envisioned that A&M would become a great place to train leaders, Buser said.

“Some of the plans were revealed to The Battalion because I was fortunate enough to be in his presence when those plans were revealed,” Buser said.

While The Battalion staff was busy following up leads and writing stories, they still maintained their normal load of schoolwork and activities.

“The editorial staff, comprised mainly of members of the Corps, had to be commended for staying up late to put out the paper and still making formation before 8 a.m.,” Buser said. “The newsroom became known as the ‘Batt Cave’ and the staff as the ‘Battmen’ because The Battalion officers were located in the basement of the YMCA Building and the staff only operated at night.”

Times start to change

As the 1960s rocked their way into College Station, The Battalion covered major changes beginning to affect the A&M campus. Reporters pounded out stories on their typewriters as the College was about to achieve university status, a name change was being proposed and a movement to admit women began.

Tumultuous times continued on the campus and in the world as the 1960s progressed. The College became a University. The all-male A&M went co-ed, the Corps became non-compulsory and the school started admitting black students. The Vietnam War exploded on the international scene, and President Kennedy was assassinated.

The Battalion and the administration clashed over coverage on a number of issues. Glen Dromgoole said one of the biggest problems that stood out to him was an incident concerning Johnny Cash and Bonfire.

The administration canceled a Cash performance at Bonfire after Cash had been arrested in El Paso and charged with smuggling and concealing drugs.

The Battalion staff editorialized that the administration was convicting Cash without a trial, Dromgoole said.

“That issue really got to the administration and put us at odds for the rest of the year,” he said. “We were not under the journalism department. We thought we reported directly to God. The administration thought they were the publisher of the paper.”

Dromgoole said The Battalion did not have much anti-war sentiment to cover on campus. The biggest concern was over the admittance of women to the university.

When Dromgoole left the paper, he and other members of his staff presented a 17-page “State of The Battalion” report to Rudder, the then president of A&M.

“We knew no bounds to our audacity,” Dromgoole said.

DeFrank vs Rudder

The tense situation between the administration and The Battalion did not improve the following year. Tom DeFrank, who had worked as Dromgoole’s managing editor, took over the position of editor in 1966-67.

On Sept. 30, 1966, the A&M Student Publications Board officially removed DeFrank and two of his assistants from their positions on the paper. Jim Lindsey, chairman of the board, said he felt the action was necessary because continued policy disagreement could only result in further harm to The Battalion, according to a Battalion article on Oct. 7, 1966.

Changing spaces

As the 1960s gave way to the 1970s, The Battalion moved to new offices in the Reed McDonald Building. Changes continued to catch up with the university, and The Battalion continued reporting on these changes in spite of opposition from the administration.

“We covered the war and what was going on [at] other campuses,” said Dave Mayes, editor of The Battalion in 1969-70. “Here the students gathered in front of the Academic Building and had debates among themselves in groups. The administration then didn’t like to see those kinds of things going on.”

Dissension struck the newsroom in the school year of 1975-76. James Breedlove, a journalism student who had never worked for The Battalion, was appointed to editor. This went against university regulations, which specified that candidates for Battalion editor must have worked on the paper for a year.

The staff considered Breedlove an outsider. In the fall semester, several editors quit and others were fired. At one point, Breedlove fired his staff, retaining only the editors. The firing was reviewed, and three reporters were rehired. Before his tenure was completed, Breedlove resigned. In his absence, Roxie Hearn served as interim editor for the last month of the semester, making her the paper’s first female editor.

In the spring of 1976, The Battalion and the journalism department began to work together. The paper used journalism students as reporters, editors and photographers to supplement the paper’s paid staff. Bob Rogers, then-chairman of the Student Publications Board, was instrumental in this change.

New times

As the 1970s wound down, the Gay Student Services Organization created a lot of stories for Lee Leschper, editor of The Battalion in summer of 1977.

In summer of 1978, Debby Krenek became the first woman to serve a full term as editor of The Battalion. Krenek went on to win a Pulitzer Prize as editor of a project with the New York Daily News and is currently the publisher of Newsday on Long Island. Kim Tyson, the first woman selected as editor for a full school year by the Student Publications Board on March 28, 1978, followed Krenek in the 1978-79 school year and then came Karen Rogers (summer 1979) and Liz Newlin (fall of 1979).

In the fall of 1986, Cathie Anderson became the first African-American student named editor of The Battalion. Anderson went on to work for the Detroit News, The Dallas Morning News and the Sacramento Bee.

More improvements

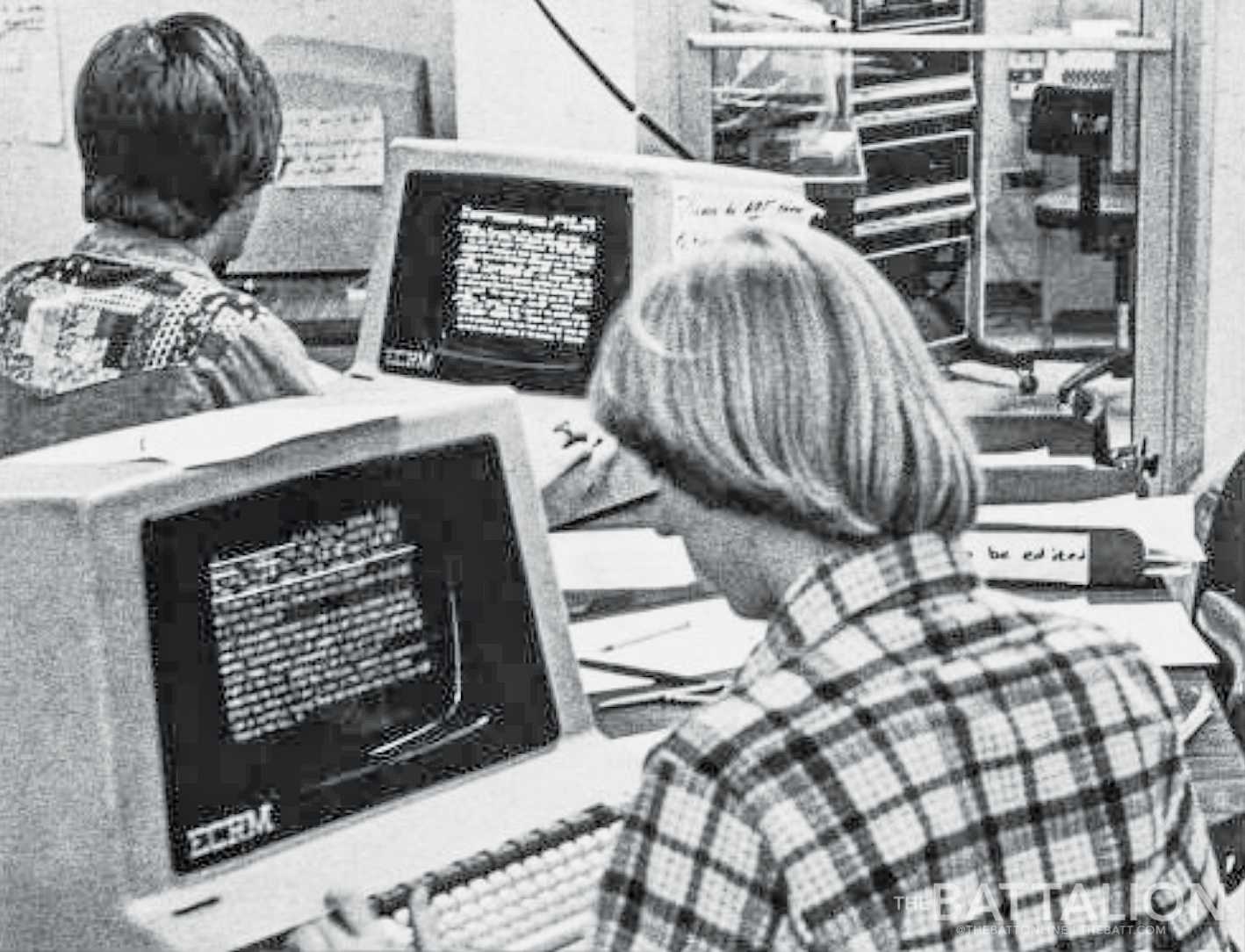

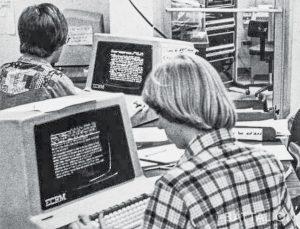

By 1984, a new computer system was installed and The Battalion editorial board began writing daily editorials.

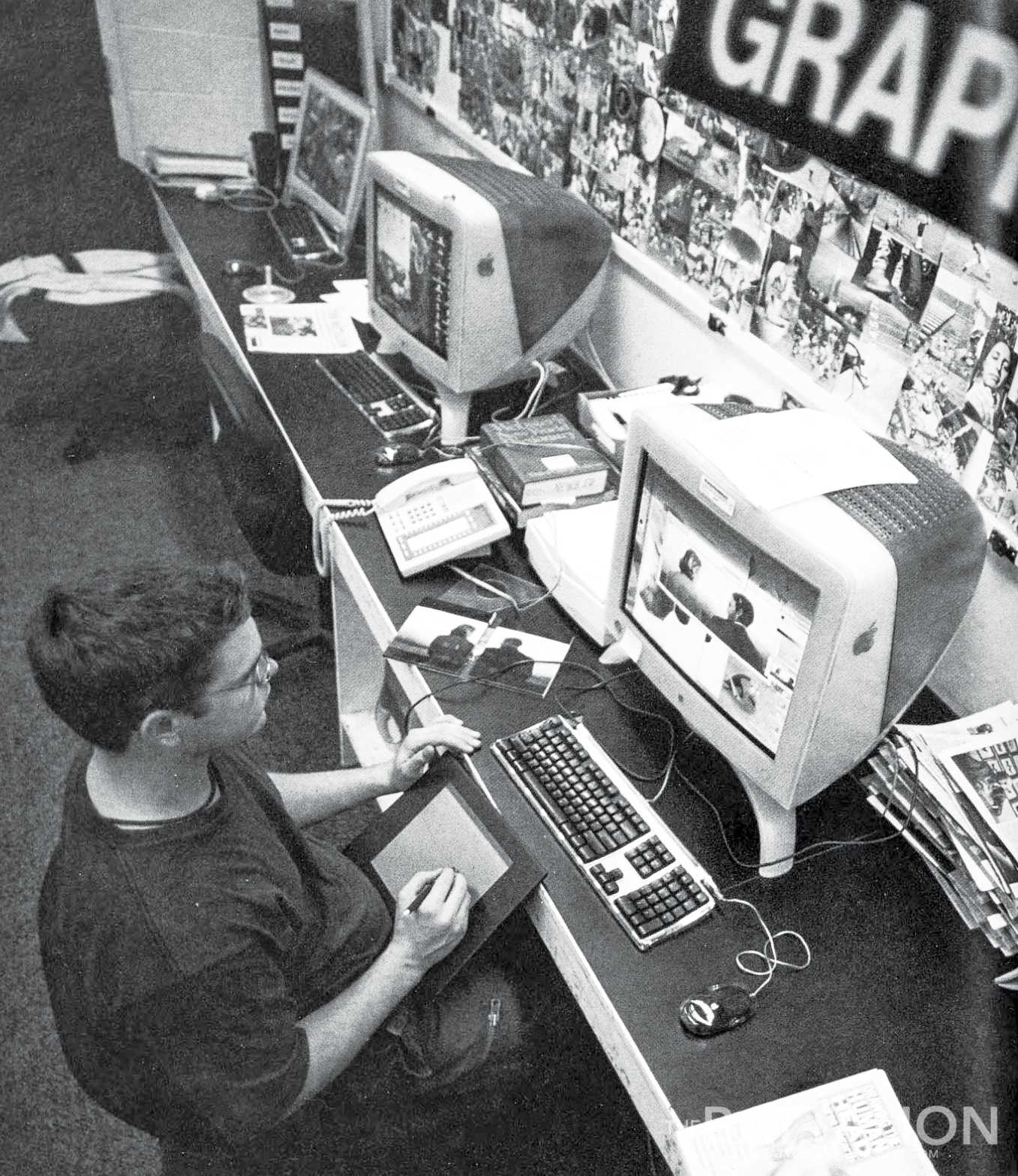

In the fall of 1991, The Battalion switched to the Apple Macintosh computer system.

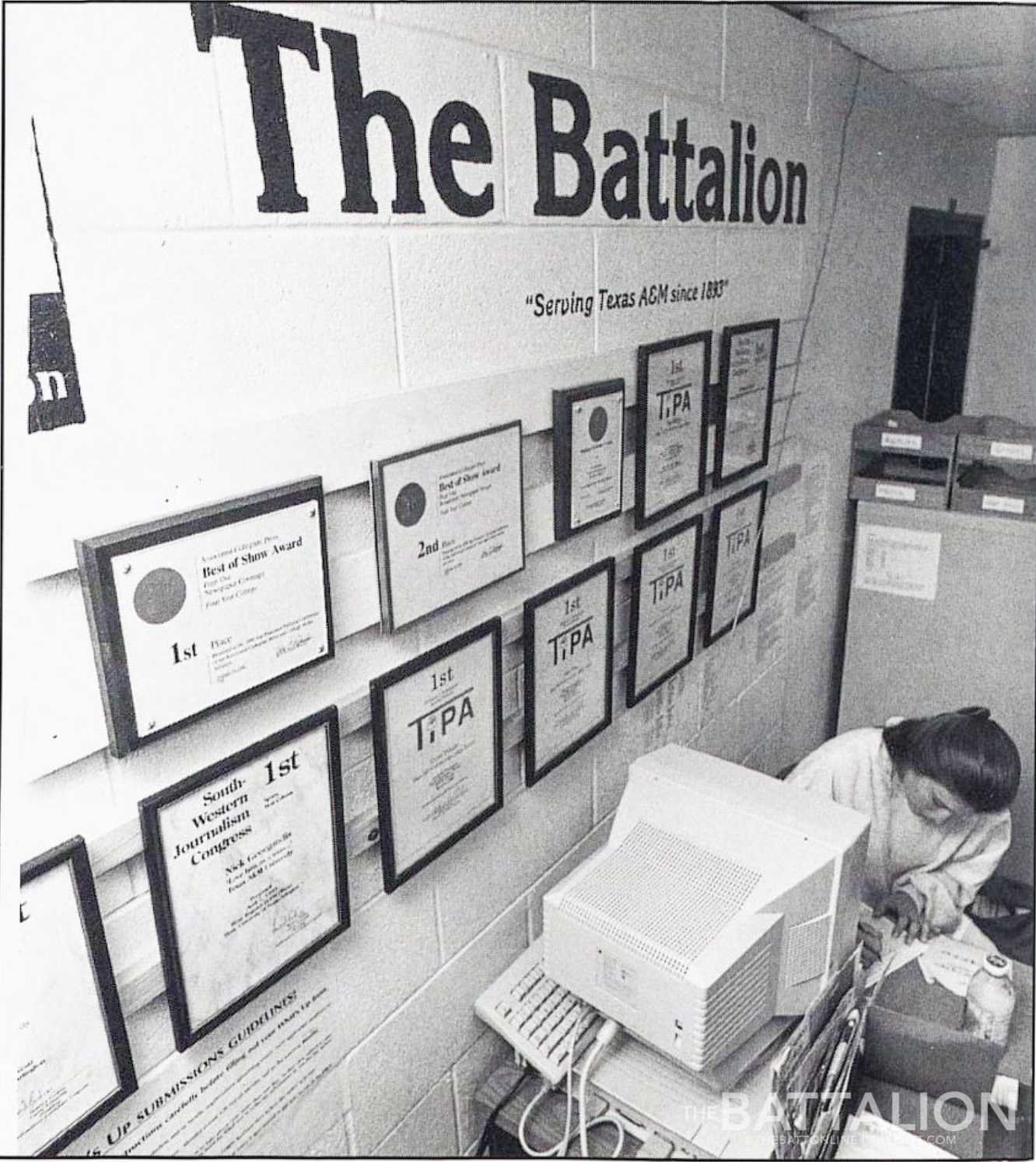

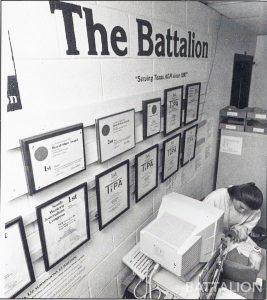

After the 100th anniversary of The Battalion, the Former Journalism Students’ Association was born. Many members of The Battalion and those who have worked in Student Media at Texas A&M have been inducted into the FJSA Hall of Honor. Currently there are 20 members, including DeFrank and Krenek.

In the fall of 1996, The Battalion started printing the front page in full color every day. This was possible because of a new off-campus printing agreement with The Huntsville Item. The five-unit Goss Community Press housed in the printing center on campus was transferred to the Instructional Printing Facility at Texas A&M-Commerce.

The printing quality of the Huntsville press made it possible to do things with design that were not possible with the capabilities of the campus press.

The rest of the 1990s and the turn of the century brought about many changes to The Battalion.

In the summer of 1997, The Battalion hired its first web editor as news from the printed paper transitioned to online content.

In the spring of 1999, the supervisory board for student publications was still called the Student Publications Board, but the board voted unanimously to change the name to the Student Media Board. At that time, the news advisor of The Battalion was added to the board as a non-voting member.

The Battalion and its new website were a go-to news source when the Bonfire stack fell on Nov. 18, 1999, killing 12 Aggies and injuring 27. Other media outlets around the state and the nation used photos and stories from The Battalion.

The Battalion’s work on that terrible night and in the days that followed was widely praised by the Department of Journalism and by journalists around the state.

In the fall of 2000, The Battalion partnered with CampusEngine.com and thebatt.com was officially born. Before then, the University’s IT department had hosted The Battalion’s content. The website has changed host sites a few times since then, and it currently works with TownNews.com, an industry leader that hosts many other college newspapers and small newspapers around the country.

The next big change for The Battalion came from 2004 to 2006 as the university phased out the Department of Journalism. After the program was officially closed, The Battalion moved under the Offices of the Dean of Student Life within the Division of Student Affairs. That also required a physical move out of Reed McDonald and to the lower level of the Memorial Student Center.

Not long after moving into the new space, The Battalion relocated once again in 2009, taking up temporary residence in The Grove between Cain Hall and Albritton tower while the MSC was being renovated. The paper was produced in a portable building until 2012 when the MSC reopened.

Breaking News

In November 2015, Battalion reporter Spencer Davis’ three-part series, “A Dark Spot in Texas A&M’s Investments,” attracted national attention. Davis’ reporting revealed that the University of Texas Investment Management Company — which handles billions of dollars of endowment funds for the A&M and UT systems — was invested in 10 of 25 companies linked to genocide in Sudan. The series received the University of Georgia’s Betty Gage Holland Award for excellence in college journalism.

In late November and early December of 2016, The Battalion found itself at the center of a national controversy yet again, as news editor Chevall Pryce broke the news that white supremacist Richard Spencer was planning a speech in the Memorial Student Center. Pryce was named reporter of the year by the Texas Intercollegiate Press Association for his coverage of Spencer’s speech and the ensuing protests on campus.

Also during the fall 2016 semester, The Battalion started rolling off the presses closer to campus, thanks to a new printing agreement with The Bryan-College Station Eagle. That same year, the paper dropped from five print editions per week down to four, and then down to three in the fall of 2017 as The Battalion continued wrestling with the same financial pressures faced by newspapers across the nation.

To provide a different style of print product for readers and advertisers, The Battalion staff produced the first edition of their Maroon Life magazine in the spring of 2017. Under the Maroon Life label, the staff has published fall and spring sports previews, housing guides, restaurant reviews and The New Aggies Guide to Aggieland — a crash course on traditions and campus life for incoming freshmen.

Throughout all of the changes, The Battalion has maintained its mission to cover Texas A&M and the community. That’s the primary goal, but The Battalion also exists to provide students with real-life job skills in writing, editing, photography, graphic design, page design, web design and leadership skills. Staff members work as a team to produce informative daily content for the students, staff, faculty and graduates of Texas A&M.

Adapted from articles by Mary Kujawa, writing for The Battalion’s 100th anniversary, and The Byline, a former publication by the Department of Journalism.

Editors note: This article has been updated to include additional details concerning the selection of The Battalion’s first female editors.

Looking back on The Battalion’s 125-year history

October 3, 2018

0

Donate to The Battalion

$2790

$5000

Contributed

Our Goal

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas A&M University - College Station. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs, in addition to paying freelance staffers for their work, travel costs for coverage and more!

More to Discover