According to Franco Marcantonio, Texas A&M geology professor, there is a chance that iron particles deposited into the Pacific Ocean during the last ice age could have affected global climates.

Marcantonio’s research began when he took part in an expedition to the Galapagos Islands to retrieve a core sample — a cutout that contains eons of sedimentary layers detailing the Earth’s geological past — from the bottom of the ocean. After bringing it back to the lab, he said he found something interesting and unusual about it.

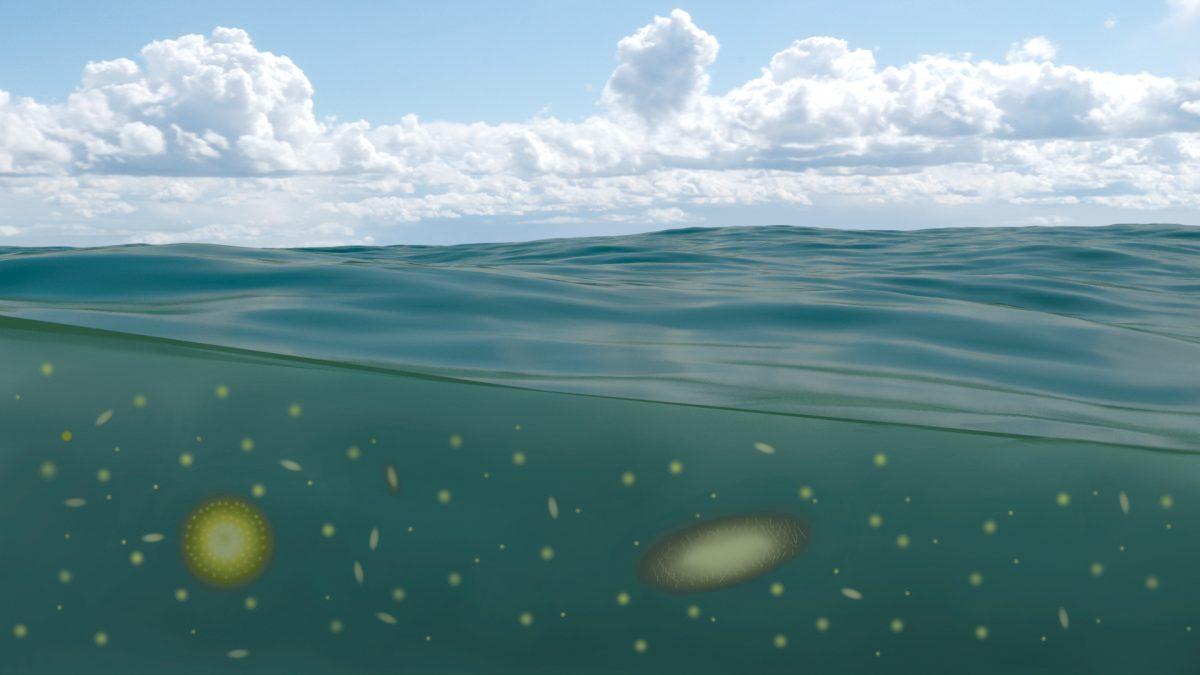

“We found eight, maybe nine intervals in the sediment core that had increased amounts of dust from the continents, and dust from the continents has iron in it, and some of that dust, it’s really fine-grained, it dissolves, and when it dissolves, it releases the iron, and iron is important because it’s an important micronutrient for plants in the ocean,” Marcantonio said.

These plants, according to Marcantonio, would mostly be algae, and while there is no way to directly tell how much algae was present in the ancient ocean, a trace element called barium can indicate the presence of algae.

Marilyn Wisler, a former undergraduate research student under Marcantonio who performed the barium analyses said that the results indicated a correlation between the amounts of barium in the ocean and what the climate was like at the time.

“With all the analyses that we had, we ended up correlating them to different climate events,” Wisler said. “The barium only occurs in the seawater, and for the fact that that could be correlated to what’s going on in the atmosphere was really interesting to me.”

Marcantonio said that his current hypothesis was that algae growth spurred by increased iron levels led to the algae absorbing increased amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, which in turn lowered average global temperatures.

According to oceanography professor Lisa Campbell, algae growth like this is possible with an increase in iron.

“Chlorophyll needs iron, that’s a component of the molecule, and also iron is important in a lot of enzymes for normal functions of cells,” Campbell said. “If iron is depleted, then the cells can be limited in their metabolic functions and their growth, so there’s vast regions of the ocean that are thought to be iron-limited.”

Marcantonio also said there was a correlation between when these pulses of iron particles were released into the ocean and when groups of icebergs broke off of Arctic sea ice in the Atlantic Ocean.

“There is particle debris on the bottom of these iceberg armadas that calve off into the North Atlantic Ocean,” Marcantonio said. “Once the icebergs melt in the ocean, the particle debris will fall to the seafloor. These layers of ice-rafted debris are deposited at about the same time we found the dust intervals in the equatorial Pacific. A fundamental part of my research is to try and figure out what exactly this correlation means and how it’s related to global climate change.”

However, according to Campbell, artificial induction of iron particles into the ocean can be very dangerous, and is not a solution to current climate change issues.

“You don’t know which phytoplankton you’re going to stimulate,” Campbell said. “There’s many thousands of different phytoplankton species in the ocean and so it’s possible that you’ll stimulate ones that aren’t very good food sources or ones that are toxic.”

According to Campbell, affecting the base of the food chain could have unforeseeable consequences for entire marine ecosystems, so while random iron deposits in the oceans had a seemingly desirable effect in the past, there is no way to know if that would be the case today with artificial iron seeding.

Heavy metal in the high seas

October 8, 2017

Photo by Graphic by Alex Sein

A sediment core showed iron particles left from the last ice age; allowing for the growth of more algae which absorbed carbon dioxide form the atmosphere and lowered global climates.

0

Donate to The Battalion

$1815

$5000

Contributed

Our Goal

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas A&M University - College Station. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs, in addition to paying freelance staffers for their work, travel costs for coverage and more!

More to Discover