In preparation for late-night storms, the Texas A&M Department of Atmospheric Sciences launched a weather balloon Monday afternoon.

Following a severe weather warning from the Storm Prediction Center, A&M’s Student Operational Upper-Air Program, or SOUP, made arrangements to launch a weather balloon before Monday night’s thunderstorm. The instrument attached to this balloon, a radiosonde, collects data necessary to help forecasters at the National Weather Service, or NWS, gain a better understanding of upper-level atmospheric conditions.

In the wake of the 2010 British Petroleum oil spill, SOUP was created with the intent to provide the NWS with information about atmospheric conditions in the Gulf of Mexico. Atmospheric sciences professor Erik Nielsen, Class of 2013, got involved with the program during this time as a rising sophomore at A&M. Twelve years later, during SOUP’s 250th weather balloon launch, Nielsen said the program’s purpose remains the same: helping forecasters narrow down what’s really going on at a particular location.

“The atmosphere is not just at the surface [of the earth],” Nielsen said. “So weather balloons are one of the most direct ways we can get information about temperature, humidity and wind as we go up [in the atmosphere].”

Thunderstorms tend to happen when air rises and remains warmer than the surrounding air, Nielsen said. Therefore, getting a vertical profile of atmospheric conditions is important for assessing the possibility of thunderstorms.

The NWS employs a system wherein specific locations across the globe host twice-daily radiosonde launches. The data obtained from these launches directly serves as a main source of information for various forecast models across the world. According to the NWS, 92 of these sites are located in North America.

Nielsen said the closest NWS offices to College Station that conduct twice-daily launches are Dallas, Corpus Christi and Lake Charles.

“We are kind of in the middle of a data gap when it comes to weather balloons, or radiosondes,” Nielsen said. “So if we have the expendables, we will launch in these cases to help [the NWS] narrow down what the forecast is really going to be.”

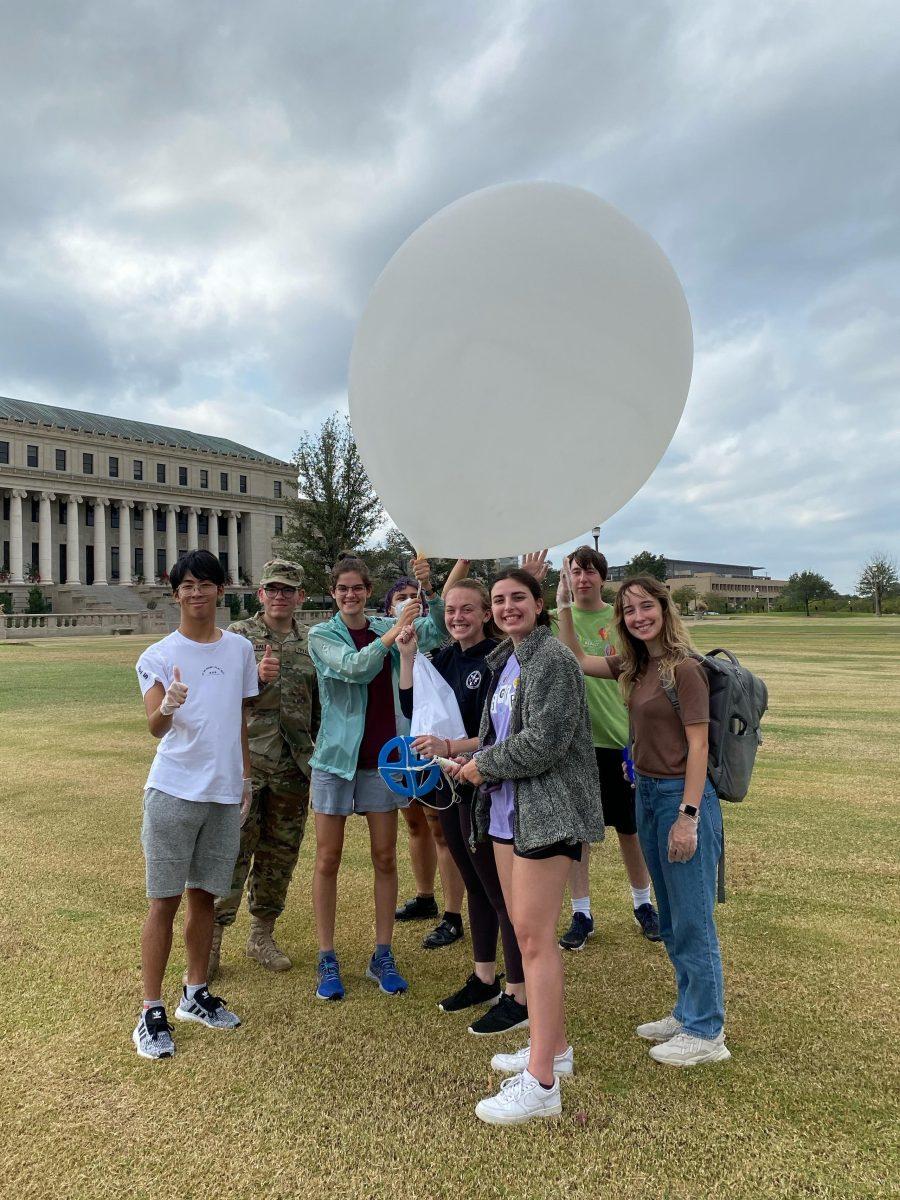

Although the decision to launch a balloon was made by professors within the department, the launch itself was almost entirely student-run. Sunday evening, a message was sent to meteorology students informing them of Monday’s launch and encouraging them to participate.

Upon arrival, the students were divided into three cohorts. One group headed upstairs to the 15th-floor observatory in the Eller Oceanography and Meteorology building, or O&M. These students were responsible for receiving the data from the radiosonde as it was transmitted in real time.

The other two groups headed outside. As one group aired up the balloon and prepared it for launch, the other proceeded to the launch site where they observed and reported present weather conditions.

Meteorology sophomore Clara Holloway said that being involved with the launch made her realize how extensive the process was.

“I got to learn about the whole process of how they set it up,” Holloway said. “They have it down to a T with how specific it is, and it’s such a big team effort.”

Once the group aired up the balloon and attached the parachute, they joined the other group at the launch site. Here, the radiosonde was attached to the balloon, current conditions were relayed via radio to the students in the O&M observatory, and Easterwood Airport was informed about the launch.

While awaiting the “all-clear”, four students stood in a line holding the balloon and its attachments: one holding the balloon, one holding the parachute, one holding the reel and another holding the radiosonde. Eventually, the countdown began and the balloon was released into the air.

Nielsen said that, as the balloon is in the air, it is radioed back to computers in the observatory and plotted on a thermodynamic diagram.

“By plotting it, we can see how the air is going to hypothetically move up or down in terms of its temperature,” Nielsen said. “If it’s warmer than its environment, then we have a chance of thunderstorms.”

Nielsen also said the way wind varies with height is important, as more rapid changes indicate a higher chance of organized storms.

“If the wind is changing fast enough with height, in both direction and speed, we might be in a scenario where we move from isolated thunderstorms to more large-scale systems or supercells,” Nielsen said. “[These systems] have the best chance of producing rotation and, potentially, a tornado.”

Ultimately, according to Nielsen, the resulting temperature, humidity and wind profile provided by the radiosonde allowed forecasters to see that there was a threat of intense winds when the storms passed through Monday evening. The NWS was able to issue warnings accordingly, meaning the goal of aiding forecasters was met.

“When the storm came through, I felt like I had done something,” Holloway said. “I got to apply so many things I’ve learned in class and I aided the NWS.”

From the hands-on process of filling the balloon, to launching it and seeing the data transmitted in real time, Nielsen said students are able to gain a better understanding and appreciation for what they’re learning.

“This is what I want to do in my life,” Holloway said. “Doing this — being able to aid in forecasting — really solidified that I’m doing what I really want to do.”