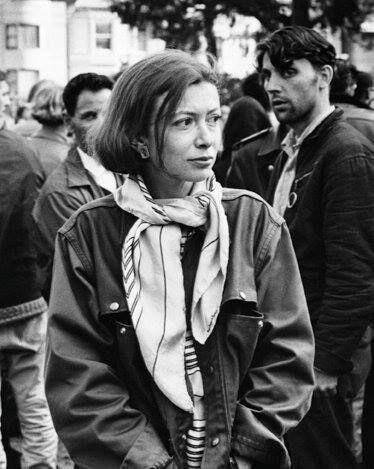

Two days before last Christmas, on Dec. 23, 2021, writer Joan Didion’s death was announced. She is survived only by her writing.

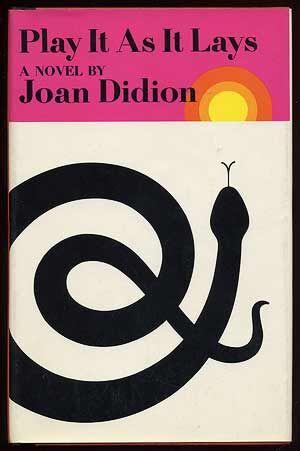

“Slouching Towards Bethlehem” and “The White Album” were nonfiction collections which depicted a fractured, gothic post-midcentury and introduced America to Didion’s singular voice. In between those two collections and buoyed by its success, in 1970, Didion released her second novel: “Play It As It Lays.”

Although best known as a memoirist, an essayist and a journalist, Didion wanted first to be a novelist. Two themes preoccupy Didion’s oeuvre: atomization and sentimentality, or stories and how they fall apart. When Didion wrote “Play It As It Lays,” her marriage was falling apart.

At this time, Didion’s husband, fellow writer John Gregory Dunne, packed a suitcase, went to Las Vegas, abandoning Didion and their daughter. Dunne documented his experience in 1974’s “Vegas.” Back in Malibu, Calif., Didion wrote about freeways, parties, affairs and Maria, a woman who no longer sees the point in any of it. “She’s coming to terms with meaninglessness,” Didion says in “The Center Will Not Hold.”

The novel takes place in Los Angeles in the late 1960s. Maria is a B-list actress in a failing marriage to a director, Carter, with whom she has a daughter, Kate, who is brain-damaged and institutionalized. While Carter’s shooting on location in the desert, Maria spends her days driving on the freeway, at Hollywood parties and hanging out with people she seems ambivalent about at most.

Mariah goes through a world where she is always misconstrued and insulted by strangers and those close to her. It is a world where affairs and arrangements are commonplace, a gothic Los Angeles. When Maria aborts a pregnancy at the behest of her estranged husband, the blood and torn flesh of the fetus become a recurring motif.

The book contains 84 chapters, sparse scenes of an increasingly senseless life. Didion strove to write books that can be read in one sitting, so as to not lose the shape of the book. Accordingly, “Play It As It Lays” contains as much blank space as it does text. Didion uses flash cuts, a technique she first employed in the titular essay of “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” and a close third-person narrator to give us peeks into Maria’s increasingly more horrifying time.

“Play It As It Lays” is an intentionally opaque book. Nuances exist abound, and the white space does little to discourage the reader from looking in between the lines. When Maria has nightmares about her aborted fetus clogging up the pipes, she cannot bear to refer to it as anything more than flesh and blood. The abortion is often referred to only by euphemism.

Discussion of the book would not be complete without discussion of Didion’s own politics, this being the same Didion who wrote an essay decrying second-wave feminism in her second nonfiction collection. Didion wrote these works before the right to an abortion had been secured, a world before “Roe v. Wade.” In the aforementioned essay, she wrote being a woman meant “that sense of living one’s deepest life underwater, that dark involvement with blood and birth and death.” “Play It As It Lays” attempts to crystallize into pristine prose these precise feminine horrors.

Blood and birth and death do not take Maria down, as much as the book would have you convinced. Instead, she is a victim of her own lack of conviction. Maria acts like a passenger in her own life except when she drives, the freeway is the only place she feels in control. When Maria goes to have the procedure she cannot bear to say, she is driven to the location by someone else. It is not a choice she would have made herself but a choice she is driven to, a turn of speech made literal. Maria is a passenger to her own abortion only to bear the physical and psychological burden on her own.

The true horror of the book is watching Maria self-destruct after. She does not so much self-destruct, implying an agency which Maria lacks, as she does acquiesce toward chaos. In the end, she acquiesces to her friend, BZ, who commits suicide. Thus completes Didion’s trifecta of domestic horror: blood and birth and death. Maria goes through these trials of femininity and emerges from grief without greater insight. “I know what ‘nothing’ means, and keep on playing,” Maria says at the novel’s denouement.

This is not a book that will comfort you through the night. Luckily for us, Didion has never looked to warm her readers’ hearts. That is precisely her appeal: She could be a victim of sentimentality, but she told us once those stories get stale.

Beneath her sometimes sparse, sometimes verbose, always pristine sentences lies a horror of disorder. Even if you are not driven to the same depths of horror, Didion’s sentences make you see precisely where she’s coming from and exactly what she means. She rarely meant to relay good news.