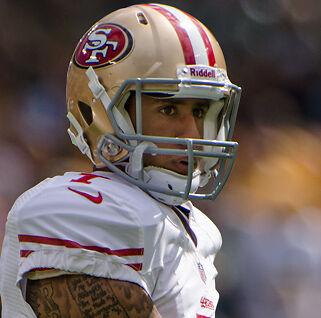

There’s no place like the center of race-based controversy, and I think Colin Kaepernick, NFL quarterback, turned activist, can attest to this.

Five years after kneeling on the neck of his future in the NFL in opposition to the all too frequent persecution of Black people in America — Kaepernick is up to his old tricks once again. “Colin in Black & White,’” a six part limited series co-produced by Kaepernick and Ava Duvernay, ventures into dangerous territory — strategically dropping bombs and lighting flares on the fabric of sports through the lens of race. It’s an exploration of the man behind the swirl of anti-American labels, before he was left sitting outside of the pearly white gates of the promised land, the NFL.

It’s also an uncomfortable, thought-provoking, “micro-aggression for dummies crash course” saturated by humor, the awkwardness of self discovery and cultural allusions. The most notorious of the bunch — a scene in which Kaepernick draws parallels between slave auctions and the NFL Combine. The scene is nothing short of unsettling. Don’t believe me? Watch for yourself. According to Kaepernick, the state of men with multi-million dollar abilities and opportunities for upward social mobility resemble chained men at the mercy of whips without rights or privileges.

Under the gaze of the gatekeepers, America’s most physically gifted and atypically talented young adults are evaluated through a series of drills and body metrics. They are graded and ranked, one in front of the other — their worth compiled into a pulp of decimal points and inches — much like the men assembled in chains. According to Kaepernick, these men are “poked, they’re prodded and they’re diligently examined to locate any defects that may impact performance before being sold to the highest bidder — dignity destroyed and boundaries busted.”

By no means are our beloved systems free from the shackles of slavery, but no one wants to recall those greivances with a cold one and a soft pretzel, or while sporting a tattered, faded and stained jersey under blue light on weekend afternoons. I’m all for “activist Kaep,” but this is irresponsible, egregious and coherently Kaepernick; it’s provocative and it got the people thinking.

Families were separated by the sharp corners of those auction blocks. People were herded like cattle. Yet, the scene slips seamlessly through time with visuals of the chained and the cherished. Slavery was not a choice, unlike playing professional football. However, the s-bomb threatens the long-standing white savior complex embedded in professional sports. “White saviorism” signifies the incessant need of some white people to rescue the underprivileged — to be the hero. It insinuates that certain communities or individuals are incapable of bettering themselves and their situations. It gushes with the idea that the white people know best, and guard the door to “better.”

It’s no secret that every year, white-faced front offices hand select from pools dominated by Black and Brown men with longevity in mind. That’s the purpose of the invasive, pokey, prodiness of the Combine — vitals are critical (i.e. vital) to the growing $9.8 billion industry. And general managers, owners and coaches know this. They provide the platform, and only the strong, quick and perceivably durable survive. So long as football is “the way out” of less than ideal financial situations — a gift to communities riddled with crime, violence and poverty — the pipeline pumps money into pockets and propaganda into our minds that our present has somehow severed ties with our past.

Kaepernick has messed with the wrong game, or maybe the white — I mean right — one.

Jordan Nixon is a psychology senior and opinion writer for The Battalion.