In September 2011, the Tevatron, the most powerful particle accelerator in the world at the time, was turned off after 26 years of smashing atoms.

The closure affected scientists and engineers from around the world, including researchers from Texas A&M. Many of these researchers relocated to bigger and better facilities after the Illinios-based Tevatron went offline, while the accelerator’s final data is still in analysis.

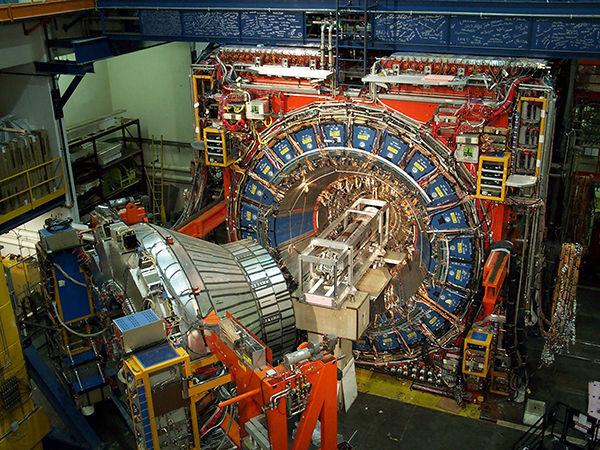

David Toback, professor of physics and astronomy, said Texas A&M conducted research with the Tevatron for many years prior to its shutdown through an experiment called the “Collider Detector at Fermilab,” focused primarily on searching for the particles that make up the universe.

Toback said he and his students continue to analyze the Tevatron’s data even though the machine has been offline since 2011.

“The data taken from Tevatron is written to a hard drive and we are in the process of finishing up its analysis,” Toback said. “I have students analyzing up at Fermilab and some are down here at Texas A&M finishing up research. The last step is getting that analysis published.”

Toback said he continues to visit Fermilab once every two months, while some researchers go more frequently.

“I used to go a lot more — about once a month. Some people go once a week,” Toback said. “But we do have some students still working there for us that are there all the time. Some of those students even received their PhD working with Tevatron in the past.”

Fermilab — the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory — is located in Batavia, Illinois. The Tevatron’s accelerator ring was four miles in circumference, allowing researchers to accelerate particles close to the speed of light to produce conditions similar to the beginning of the universe.

Toback said in order to be updated when he is away from the laboratory, he receives data through video conferencing and a special computing system.

“We do enormous amounts of communication, typically with a lot of video conferencing,” Toback said. “We also have set up our own computing system such that we can receive data from Fermilab efficiently.”

Toback said Tevatron was turned off in 2011 because it was outdated and another particle collider, the Large Hadron Collider, located in Geneva, Switzerland, had taken its place as the largest and most powerful particle collider.

“It was a really sad day when Tevatron was turned off,” Toback said. “The experiments went beautifully, but we’d had 20 years worth of research and data and, frankly, the LHC had more. It was just a matter of time before it was superseded.”

Toback said several of the researchers that had previously been a part of the research with Tevatron moved to the LHC upon its closure.

“Most of them went to LHC because there are just certain questions we had at Tevatron that can only be answered at LHC,” Toback said. “After realizing those questions couldn’t be answered at Tevatron, people just kind of dispersed. There are only a couple of us left finishing up data analysis. There are actually enough people working for LHC now that an LHC center was even built at Fermilab, even though the actual conductor isn’t there.”

Ricardo Eusebi, physics and astronomy professor, said some researchers at Fermilab who worked with Tevatron had already begun work at the LHC before Tevatron was turned off.

“A lot of people knew Tevatron was going to be turned off,” Eusebi said. “When people hear that kind of news, they search for their next move. A lot of people, including myself, began working in about 2003 with the construction of the LHC in Geneva.”

Teruki Kamon, physics and astronomy professor, said while the turning off of Tevatron marked the end of CDF, which had made up a large portion of his career, the researchers involved in the experiment were granted new opportunities in the wake of Tevatron’s closure.

“I was there to see the first proton, anti-proton collision in 1986, and I was there for the last in 2011,” Kamon said. “Every experiment has its last day. It’s sad, but it was also a good deal for many researchers because they were given new opportunities at other places.”

Eusebi said Tevatron once made Fermilab the center of particle physics research.

“CDF was like no other experiment,” Eusebi said. “It was small, and it was close to many hearts. It was sad to see it end.”

Tevatron research continues despite closure

October 20, 2014

Provided

The Collider Detector’s internal machinery is shown to the right. A&M researchers used the collider until the Tevatron closed in 2011.

0

Donate to The Battalion

$2790

$5000

Contributed

Our Goal

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas A&M University - College Station. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs, in addition to paying freelance staffers for their work, travel costs for coverage and more!

More to Discover