All students find the first days of college challenging, but for those with visual impairments, the challenges present a much more complex maze, especially regarding equal access to education.

For students with learning and physical disabilities, Texas A&M’s Department of Disability Resources aims to disentangle the path to academic success. A recent feat by the department involved translating thousands of math textbook pages into Braille to accommodate visually impaired students.

The labor-intensive and lengthy project resulted from math lecturer Vanessa Coffelt requesting further accommodations for one of her students with visual impairments. The end product was around 2,300 pages of Braille translation produced in collaboration with the Department of Mathematics.

“[The Department of Mathematics] had worked with the Office of Disability before the spring semester, trying to make sure that [coursework] was as accessible as possible given that it was a math textbook,” Coffelt said. “I provided all the group work activities and lecture notes that would be used in the course for the student who needs them to be translated.”

Despite Coffelt’s understanding of different levels of accessibility and their needs, she said she never worked with a student who needed Braille translations before this year. According to Coffelt, explaining and applying concepts like a matrix to a student who has never seen one poses a unique challenge.

“In a math class, there’s a lot of visuals in terms of the graphs we use, and I had to change how I approached not only the examples I did in class but [in] the simple descriptions given,” Coffelt said. “It was a change to read the problem aloud to the class. I wanted the students to have that auditory description. Describing what picture or graph the students saw became more important.”

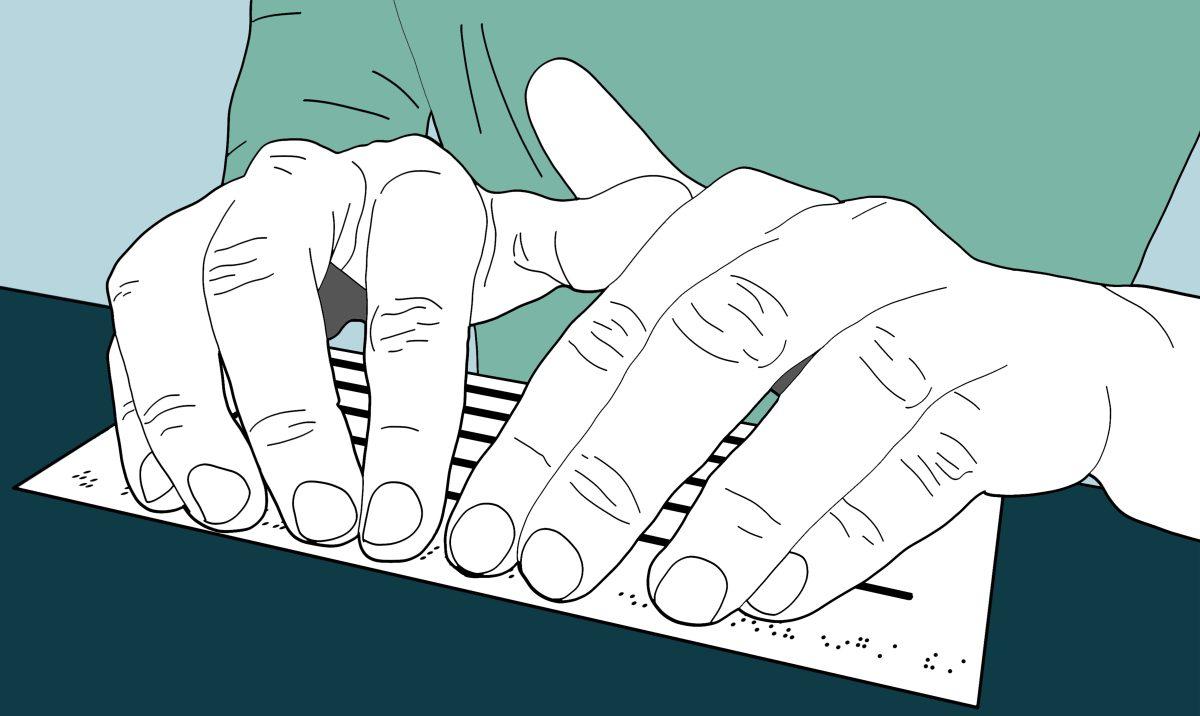

According to A&M’s Department of Science, an embosser was used to produce the Braille text and tactile graphics by punching dots, patterns and textures into thick cardstock. The type of paper or the number of holes in textbooks may seem trivial to most students, but Braille is a unique code that requires great care and attention. Creating title cards for each separately-bound package, binding the content volume and selecting tractor-fed paper as the Goldilocks of Braille translation — everything needs to be just right, and translation is no easy task.

Visually impaired students have typically been deterred from pursuing careers in STEM fields, with significant barriers to converting visual, detailed information into intelligible information. Luckily, projects like these at A&M challenge the notions about how students can connect and interact with STEM concepts.

Biomedical sciences junior Lindsie Darvin, a visually-impaired student, said she applauds the strides Aggies have made to create a more inclusive home for all students.

“I know that the translation of these math pages was a costly and time-consuming endeavor, and I believe this speaks volumes to the inclusivity seen at Texas A&M,” Darvin said. “One of the first things I noticed during my time on campus was the buses that announced when they were turning. This greatly helps the visually disabled community with campus navigation and usability.”

As a member of the Student Advisory Board for Disability Resources, Darvin said one of the most significant changes students have recently seen is the introduction of Accessible Information Management, or AIM, the student portal for those with disabilities. Introduced last year, Darvin explained how AIM allows students to send accommodation letters to professors and more efficiently communicate their needs with their instructors and the Disability Resources office.

Living by the statement, “If it’s not accessible, it’s not acceptable,” Darvin is dedicated to making STEM education more obtainable.

“As a visually impaired person majoring in biomedical sciences, STEM courses have always brought a unique challenge for me,” Darvin said. “So much of STEM, particularly the medical field, is about how things exist in space and visual learning. Hopefully, with more changes like this, we can make STEM classes more accessible for the blind and visually impaired.”

Still, Darvin believes the ultimate solutions to these learning barriers are not yet in reach. To improve access for everyone, Darvin urges A&M and other higher education institutions to continue to help students envision a brighter future. She also encourages students with visual disabilities to see their passions and professions through.

“Don’t settle for less just because you don’t want to inconvenience someone,” Darvin said. “It’s your right to receive the same education as everyone else, even if that means that you need accommodations to help you get there.”You have been given a unique perspective in life. Find out what that means for you, and then go change the world.”

To support Aggies with disabilities or to donate online to the Disability Resources Improvement Fund, visit the A&M Foundation giving portal.