Texas legislators aim to ban “sexually explicit” books from public school libraries, opting to only allow “sexually relevant” books that require parental consent for students to read.

Proposed by Republican Rep. Jared Patterson, H.B. 900, or the READER act, would have book vendors rate books based on how they include content relating to sex, such as “sexually relevant” or “sexually explicit” books.

“HB 900 will pave the way to protect children from graphic content within schools,” Patterson said in a statement. “The innocence and safety of our children is paramount …”

After Patterson filed H.B. 900 on April 7, the legislation was prioritized by House Speaker Dade Phelan. It was quickly voted out of committee by a vote of 10-2, with three Democrats joining seven Republicans, advancing it to the House floor.

The bill then passed in the House with a 95-52 initial vote on April 19. Currently, the legislation awaits a final House vote before being sent to the Senate.

If passed and signed by Gov. Greg Abbott, the bill would require book vendors to rate books based on the “presence of depictions or references to sex,” according to The Texas Tribune.

Books containing sexual content would be categorized as either sexually explicit or sexually relevant, with the prior banning content that does not directly relate to the school’s curriculum and “describes, depicts or portrays sexual conduct … in a way that is patently offensive …,” according to the act, with section 42.21 of the Texas Penal Code defining “patently offensive” as something “so offensive on its face as to affront current community standards of decency.”

Sexually relevant content would require a student to have parental consent to read it rather than it being banned outright. The requirements for the label are the same as sexually explicit material, except sexually relevant content requires the book to be “directly relevant to the curriculum.”

The act was protested during its questioning on April 19, with protestors holding a “read-in” protest in the Texas Capitol Rotunda while holding signs stating “Teach The Truth.”

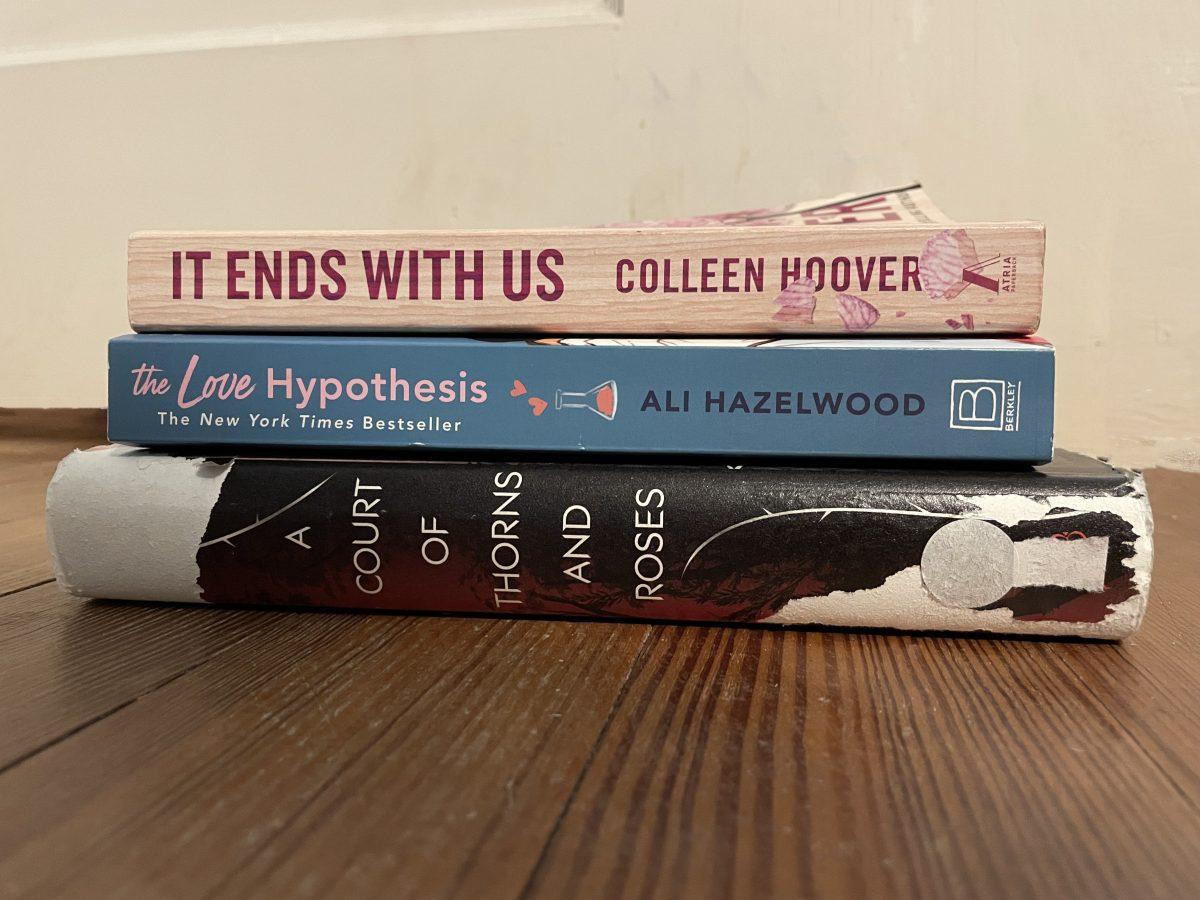

“Banned books are not new, but they have gained new relevance in an escalating culture war that puts books about racism, sexuality, and gender identity at risk in public schools and libraries,” Democrat Rep. Ron Reynolds said on the House floor. “The books most frequently challenged tend to have certain themes in common.”

Reynolds continued by stating that these bans usually target books that focus on LGBTQ+ issues and have protagonists of color.

Patterson pushed back during the debate by arguing that an amendment to the bill he authored states books “cannot be prohibited based on ideas contained in the material or the author or characters’ personal background,” according to KERA News.

“This is not a race issue or anything like that,” Patterson said to KERA. “This is a problem with sexually explicit material.”

Texas A&M students like chemistry freshman Grace Jackson said she supported restrictions on books in schools, but only to an extent.

“I don’t think many books should be banned for schools,” Jackson said. “I think certain books should be regulated. When we start banning books, then that starts getting into our freedoms.”

But on the topic of sexually explicit content, Jackson voiced her openness to restrictions on it in public schools.

“Kids’ minds are very impressionable, so I would kind of agree [on] those topics,” Jackson said. “I feel like the books that schools should be reading should be ones that have impact in the literature world.”

Agricultural economics freshman Navy Neidig shared a similar sentiment regarding the dangers of banning books.

“I think that there are some books that should be kept around because we can learn a lot from them,” Neidig said. “I think that some people want to ban them to hide the truth, and I think that that’s wrong.”

Like Jackson, Neidig was also open to restricting books with sexually explicit content.

“I do think we should protect younger audiences from sexually explicit books, but I also know that there are some pieces of literature that are really powerful that may have some scenes that make people uncomfortable,” Neidig said. “I think it really depends on the maturity level of the reader. There can’t be a blanket statement for everybody.”

Both students agreed that while such content should be limited in public schools, those limits should not affect universities.

“Most students that start college are 18, and by law, that defines you as an adult,” Jackson said. “As an adult, you can make those decisions on whether or not to read books or not. At this point in our lives, we are old enough to make those decisions.”

Neidig agreed, stating that by the time a student reaches college, they already “know where they stand” on such topics and shouldn’t be subject to restrictions. Neidig also emphasized that an overarching book ban would be counterproductive when determining restrictions.

“There’s not a one size fits all [solution],” Neidig said. “It’s not a black or white answer. I think it really depends on the book. It depends on the reader. It depends on the message that the book is trying to convey, so I think it really has to be evaluated on that rather than just saying ‘This is a good book, this is a bad book.’”