I wouldn’t be here without my mom. This should be pretty obvious, but it’s one basic truth that just doesn’t occur to most people going about their day. The extent, impact and duration our birth-givers have in our lives varies, but we all came from somewhere.

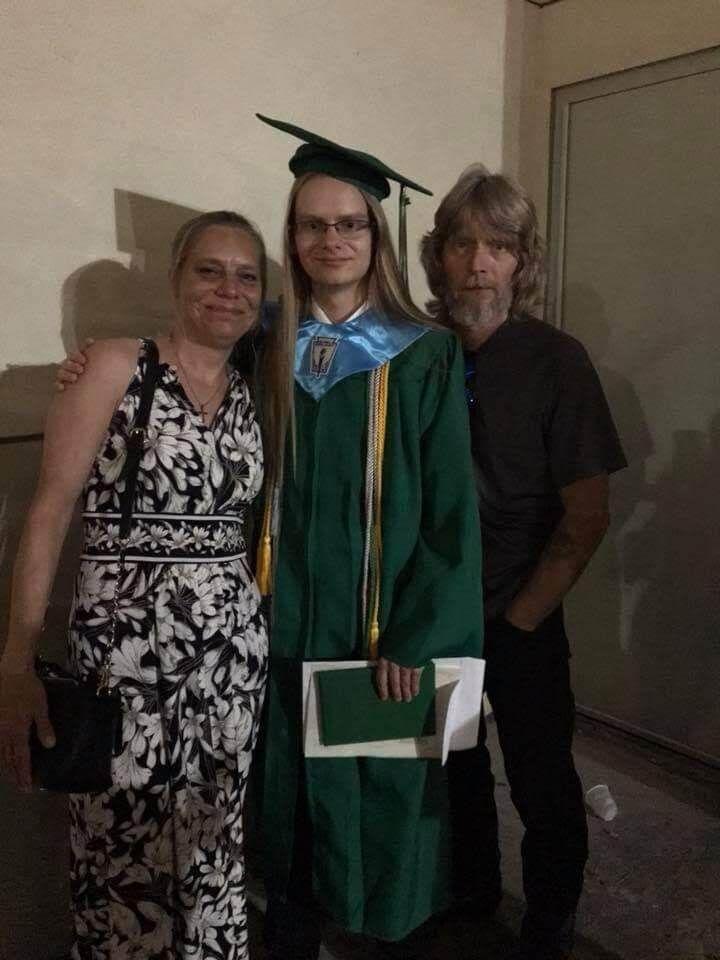

Mine and my mother’s relationship began, unsurprisingly, on the day I was born at Campbell’s Memorial Hospital in Weatherford. We started off on the wrong foot after I rewarded her nine months of carrying me around and her hours of hard labor by pooping while being born. This messy situation forced my mom into taking antibiotics for a few months, delaying breastfeeding, which I credit with half of all my failings and shortcomings today. When you gotta go, you gotta go. The rocky start to this relationship was foreshadowing for our future dynamic. Sometimes I’d be a little shit and sometimes she would be, but despite all that, we’d never throw the baby out with the bathwater.

I look back at my early childhood through rose-tinted glasses. The first six years of my life might as well have been perfect. But at age six, everything went downhill. My parents divorced, and fearing she’d lose custody, my mom tried to run away with me and my two siblings to the Great White North of Canada. We made it as far as Kansas.

You might be thinking, “No one in their right mind would try something like that,” and you’d be right. My mom struggled with a methamphetamine addiction beginning in her early teenage years. She could go years without relapse, but eventually something would always give. Hard times and bad company were often where it reached its crux. During these times, I saw firsthand how the illegality and stigma surrounding hard drug use forces people into the periphery of society. Often, the people drug users are forced to trust, rely on and relate to are other users.

Through a long series of bad decisions and worse luck, my whole family has had trouble with the law for almost as long as I can remember. My dad and grandma were legally robbed at gunpoint by the police for music equipment and steak knives.

By far, my mom got the worst of it. Her addiction and association with other addicts put her in the scope of local law enforcement more than once. In one instance, she managed to flee on foot after being stopped one rainy night. The police caught up to her, knocking her unconscious and breaking some ribs in the process.

The next day, my mom woke up in the hospital with her truck impounded. Afraid to leave, she was sure the cops would be coming for her in the hospital. A nurse assured her if the police wanted her, they would have been waiting for her when she woke up. She never reported the incident, mostly because she was grateful to not be back in jail and didn’t want to push her luck. That wasn’t her first bad run-in with the police, but it was one of the worst. She was always much more afraid of encountering police after that. What was supposed to be a symbol of safety instead made her heart drop. Today, blue and black uniforms still remind me of times when a prepaid phone call was the only way I could reach her.

Part of why she was jumpy enough to have fled that night was because she had been arrested not long before after a passenger in my mom’s car had magic mushrooms in her purse. The charges were dropped because of negligence on the arresting officer’s part.

The passenger was a woman who my mom had invited into her house while she got on her feet. This was a common occurrence throughout her life. She knew what it was like to go through hard times, and this gave her exceptional empathy and compassion toward strangers in need, even at risk to herself. When times weren’t as hard, she was an active member of the church. The connections she made there can attest to her sense of self-sacrifice. Anyone who encountered her knew she wore many hats —- a foster parent, volunteer at the community caring center, animal-lover and so much more. She was always willing to help out anyone or anything who needed it. Despite not being able to rehabilitate herself, she was always happy to take on kids, strangers, wild rabbits — you name it — all in the hope that she could leave them better than she found them.

She dabbled in just about everything, from dog grooming to car repair. She was a bit of an eclectic eccentric and had an unmatched curiosity and a genuine thirst for life. As a result, surviving and making do in hard times was her speciality. A former step-dad of mine described her as a hustler in that regard. She’d learn and adapt on a dime and was always trying to teach others — though I was less than receptive to most of these lessons.

Her grit came in handy when, at the age of 13, I was diagnosed with a germ-cell brain tumor, which I credit with the other half of my shortcomings and failings. She stuck by me every step of the way, every chemotherapy and radiation session, every doctor’s appointment. I just couldn’t shake her, no matter how hard I tried. I was exhausted from the constant attention. Though, looking back, I now realize that without her, I’d have been lost. She was my rock throughout that whole experience. Most people would hesitate to call themselves a momma’s boy — not me, for good reason.

My mom loved music. So much of my childhood was spent listening to my mom sing along to the car radio, coming up with sillier versions of the lyrics or just genuinely jamming along. She was constantly drawing and writing notes for herself everywhere, and she displayed intense emotion and purpose when expressing herself, no matter how trivial. Her calling card, in the sense that she plastered it in the margins of anything she could get her hands on, was three hearts, one for each of her kids. A moment that sticks out in my mind: during a rough patch, she wrote the lyrics of “Nothing Else Matters” by Metallica on a stand-up mirror in her room. I’ll always remember how she sang that song, like it was made for her specifically. She didn’t care how silly that made her look. In fact, she reveled in it.

She was a free spirit, to say the least.

She also deeply cared about her family, making sure her kids ended up better off than she was. She pushed me toward higher education when others in my life discouraged me. She didn’t go to college herself, thus I’d become the first in my family to do so, and she was always my biggest supporter in everything school related. She brought me to Texas A&M for my New Student Conference. Of course, she immediately broke rule No. 1 of any college campus and made a B-line to feed the squirrels outside Sbisa Dining Hall.

“It’s so freaking cute!” she said, inches from the terrible jaws of the buck-toothed hellion. Being the spoilsport that I am, I tried to dissuade her with a half-hearted, “You probably shouldn’t.”

Everything wasn’t all cute squirrels and sunshine, though. You’ve probably already realized that this isn’t strictly a happy story. Before starting my first semester at A&M, my mom was diagnosed with uveal melanoma, a rare eye cancer — just our luck. My mom didn’t have health insurance and was only able to qualify for Medicaid if she didn’t have a job. She was single and supporting herself at this point in her life. Cancer is something you can never really plan for, and being forced to jump through hoops while making no money didn’t help the situation. She did manage to receive experimental treatment in Houston while working under the table to support herself. Her wide variety of skills paid off —- she was grooming dogs, collecting copper and doing odd jobs to keep herself afloat. Months passed and we were hopeful. She had always been one of the strongest people I knew, and cancer couldn’t stop that. But, the experimental treatments didn’t work as well as doctors had hoped. Eventually, she just kept getting shuffled between hospitals in Houston and Dallas-Fort Worth because they couldn’t figure out what to do with her.

No matter how sick she got, I thought she was invincible. Part of me always thought she would recover and bounce right back, because that’s what she had always done. She’s the strongest person I’ve ever known. Tough as hell, she had been likened to a cockroach for her resilience, and she took that as a compliment.

In December 2019, just after Christmas, she was admitted to the hospital. The cancer had spread to her liver. Even then, as doctors told her that her odds were slim, I still didn’t really believe them. I got to pay her back for all the time she spent with me in the hospital, sticking by her side for just about every day of her stay. She died holding my hand.

Reality didn’t set in until her heartbeat became too faint to detect as each breath became more staggered than the last. I’m not sure how I knew, but the moment she breathed her last, I knew. My world was shattered. All the doubt and denial that had been shielding me for years was chipped away in minutes. The dam had burst, and in that moment I had no idea what I was going to do. My rock was gone. The one phrase I could muster over and over: “I’m not ready.”

I guess you never really can be.

Despite how hard it was, looking back, I’m glad I was there for her in the end. The last few years of her life were pretty unstable. Addiction had crept back in, as it tends to do, and I was one of the few members of my family that stuck with her even as life was at its hardest. Some in my family felt that cutting off contact and showing tough love would snap her to her senses. Others just did not feel that she was worth the time and trouble. I knew better. For many people, addiction is just a fact of life.

Despite the seemingly unshakable label, what we call an addict is a million other things as well. When you think of them in terms of their disease, you can lose sight of their humanity. The world we create in our minds is often populated by headlines and statistics instead of real people. For many, strangers are just flimsy casts made to fill a mold for whatever an individual wants to believe about the world. The good, the bad and everything in between can’t be done justice posed as a cardboard cutout.

I’m glad for all the experiences I got to have with my mom and for who she was as a person, worts and all. As much as she disappointed me, she inspired me tenfold. When I grow up, I want to be more like her. I like to think I already am. I’ve picked up lots of sayings, songs, puns and other mannerisms that she used to be so fond of. Her free spirit, creativity and compassion for others have become active goals for me to reach toward. Often, I catch myself copying her old mannerisms. I’m not sure exactly when this started, I used to be embarrassed and exhausted by them at times. But now, they act as little reminders for when I miss her the most. It’s cliche, but you never really know what you’ve got until it’s gone.

My mom had always been very upfront about death. She had always said she wanted a party instead of a gloomy funeral —- a celebration of her life. I was determined to make sure her wish was carried out. Fittingly, I was the most responsible out of all of our family in planning the funeral. I’d like to think I made good on her wish. It was certainly upbeat and colorful, by funeral standards. I left at the end of the service with a mountain of food made by church grannies to take back to College Station to start my sophomore spring semester. I know she wouldn’t have wanted that any other way.

She isn’t going to see me graduate in May, but I know she’d be proud of me. I wouldn’t be here without her, so when I walk across that stage, I’m walking on behalf of both of us.

In a way, she’s not really gone — I’m here. Everything she’s ever taught me, intentional or otherwise, is a real and measurable part of who I am today. We live on through our impact on others and by the mark we leave in the world. My mom’s impact is far from over because she’s got me to carry on her legacy. The moral of the story is far from, ‘Life is sad, then you die.’ To unapologetically carry on with the cliches, it isn’t about the destination, it’s about the journey, and the people that help you along the way are always the highlight.

When it comes down to it, she’s not just going to be remembered as an addict, a cancer victim or even just my mom. Because she was more than all those things. She touched so many lives and left a lasting impact on everyone she touched.

My final thoughts: Take the same approach to the people that you meet in your life. Take the good with the bad, the light with the dark. People aren’t going to fit your ideals. We need to give them the freedom, tools and support so we can help each other make the best out of it. Stigma and ostracization often do just as much harm, or more, than drugs ever could. In the end, we’re all here for each other, for better or worse. So, be there for the ones you love.

And nothing else matters.

Zachary Freeman is an anthropology senior and opinion columnist for The Battalion.