Flipped classrooms — a teaching style where lecture videos teach material and class-time is used to answer questions — are an attractive educational tool that is planned for A&M’s future engineering classes. Their promise, however, may fall flat, and the college should reconsider its implementation.

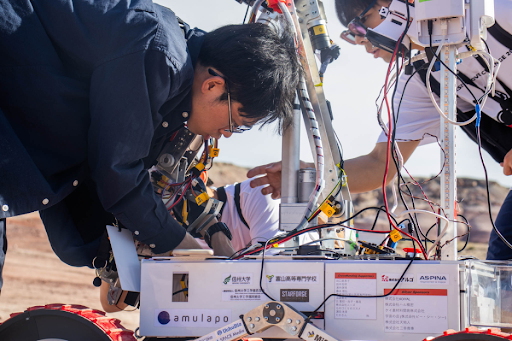

The College of Engineering has embarked on a controversial program to boost the total enrollment of Aggie engineering students to 25,000 by 2025. The largest area of relative growth will be in online masters students, but the most visible area will be in the undergraduate student body in College Station. Flipped classrooms are just one of the ways the college hopes to meet this demand, but their use is not as beneficial as the college may think.

The promise of flipped classrooms has enchanted education administrators around the country, and the large “hits” of online education sources — such as Khan Academy’s almost 1 billion total views — seem to show that flipped classrooms can work. However, my personal experience and those of my student peers — as well as emerging scientific consensus — show that flipped classrooms are no substitute for a real teacher, a proper lecture hall and good old-fashioned notes.

Sitting in a classroom and “dancing” with the lecturer through a new concept is fundamentally different than watching a pre-recorded video. In a face-to-face lecture, different neural pathways are activated and material seems to stick better than when viewing a video, as the BBC reported in its analysis of the Organization of Economic Co-operation and Development’s study of technology in classrooms worldwide.

That is not to say that online notes are useless. I made an A in Calculus III only because I could fall back on Salman Khan’s pause-able and rewind-able explanations two days before my final — and there’s the rub. Flipped classrooms are perfect avenues for re-processing a previously exposed-to subject or fine-tuning a certain subject, but they are much less effective at introducing students to something entirely new, as the videos in ENGR 111 and 112 try hopelessly to do. There’s a reason MIT and its globally-distributed courses are recorded in lecture halls equipped with simple chalkboards.

The college’s push for “active learning” at the expense of traditional lectures is similarly misguided. Rather than work with professors to supplement lectures with more engaging labs or design-oriented assignments, the college is trying to force technology onto existing lectures that are best processed with the mighty pen.

Indeed, psychology researchers are increasingly observing the longer-lasting benefits of writing words down compared to typing those same words out. When cognitive psychologists at UCLA and Princeton tested students who wrote their notes against students who typed, the writers performed better than the typists — even a week after their shared lecture.

I’ve experienced first-hand a small — but not insignificant — percentage of the difficulties in communicating and implementing strategies through my involvement on campus, and I’ve felt the pressure to adopt new trends or risk losing industry support. However, it is because of this passion for A&M and my desire to see us continue as a world-class institution that I must inform the college that its deviation from tried and true education methods is concerning, that there is a better way to educate future Aggies and that students would be honored to help find the equilibrium.

Farid Saemi is an aerospace engineering junior and former president of Texas A&M’s chapter of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics.