Carlton Caper did not mince words in his letter to The Board of Trustees: “I had hoped not to intrude on your summer,” he wrote, “but we seem to have a crisis on our hands.” At issue was a group of college students intent on starting a local chapter of Gays and Lesbians Organized for Action (GLOA), and as president of the university, the ultimate decision on whether to accept the application was Caper’s.

(I’ve got a story for you, Ags…

The letter on which this first chapter is based was published in 1997 in Robert M. O’Neil’s book, “Free Speech in the College Community.” It appears to be the only extant copy available to the public. Unfortunately for both journalists and historians alike, the letter neither mentions the date on which it was written nor the college from which Caper was writing. As such, those details have been lost to history. However, for reasons that will soon become clear, we can safely say two things about the letter. First, that it was written after the year 1984. Second, that Caper was not writing from Texas A&M University.)

It wasn’t that Caper harbored any personal animosity toward his gay students. “Some of my friends are gay,” reads one passage of his letter. But it simply had to be acknowledged: The question of recognizing the GLOA remained a “tough issue.” According to Caper, other university chapters had encouraged students to join “off-campus same-sex groups.” They had promoted “active support of gay and lesbian causes.” Some had even orchestrated “gay awareness rallies” at which “homosexuality was openly practiced.” Alas, exactly what Caper meant by this was left tantalizingly (and perhaps purposefully) unclear. Still, one thing was certain: If he didn’t recognize the GLOA, the school could expect a lawsuit.

Compounding Caper’s problems was a conservative campus group: Rush for Freedom. Named for the infamous Rush Limbaugh, “The Rush People” heard of GLOA’s application and were out for blood. If Caper recognized GLOA (thereby entitling the organization to university funds), Rush for Freedom would themselves sue the university, claiming the entire student fee structure was unconstitutional. In their view, it would be a form of compelled support for an organization whose message “they abhor[ed] and fervently wish[ed] to avoid.”

But there was more. Caper hadn’t yet informed The Board of this, but recently the brothers of Lambda Gamma Lambda had participated in some “incipient and very worrisome gay-bashing.” According to Caper, they had “produced a tasteless skit with really dreadful homophobic jokes, ridiculing gay and lesbian lifestyles. A few of the brothers dressed in crude drag, holding hands and kissing on stage, speaking in mock gay voices, and doing other things that not only the few gay students[,] but many of the straight students in the audience found extremely offensive.” Caper did not mention whether the brothers of Lambda Gamma Lambda were aware that the Greek letter which appeared twice in their name had been a symbol of gay liberation since the 1970s. Nevertheless, the student council was demanding the university punish the fraternity in some way. The dean of students, meanwhile, was insisting on respecting the fraternity’s free speech rights.

And after all this, there remained yet one more issue: Their university was in a conservative state with conservative alumni and a conservative state legislature. Caper feared these groups “just wouldn’t understand.” So he laid out the situation as plainly as he could: “[These groups] would make life very hard for us if we voluntarily invited in a gay and lesbian group. We may not have [the] kind of luxury to make the choice.”

So Caper did what any respectable university president would do in his position: He covered his behind. He looped in the university’s general counsel.

Perhaps reading between the lines (it could not have escaped their notice that despite all the talk of student rights, GLOA’s rights had not been mentioned), the general counsel answered the most pressing question first: “Can a public college or university deny recognition to a student organization because the group’s goals or actions clash with the values of the institution?”

The short answer was no.

To be sure, there was no denying that universities retained the ability to approve and deny recognition to would-be student organizations. Among other reasons, student groups have priority access to university resources, such as student fees. But there were some criteria on which schools could not rely.

One example came from a 1972 Supreme Court case in which a public university had denied Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) recognition because their “philosophy was antithetical to the school’s policies.” The Supreme Court wasn’t having it. In Healy v. James — a landmark decision which in many ways defined the legal relationship between a public university and its students — the court ruled that “the mere disagreement of the [college] President with [SDS’s] philosophy affords no reason to deny it recognition.”

The Supreme Court did, however, leave universities some wiggle room: “A college administration can impose a requirement,” the court wrote, “that a group seeking official recognition affirm in advance its willingness to adhere to reasonable campus law.”

And so the question remained: How “reasonable” did campus law have to be before a university could infringe upon students’ constitutionally protected freedoms? The Supreme Court hadn’t yet said, and so the lawyers had to dig deeper. They dug into circuit court rulings.

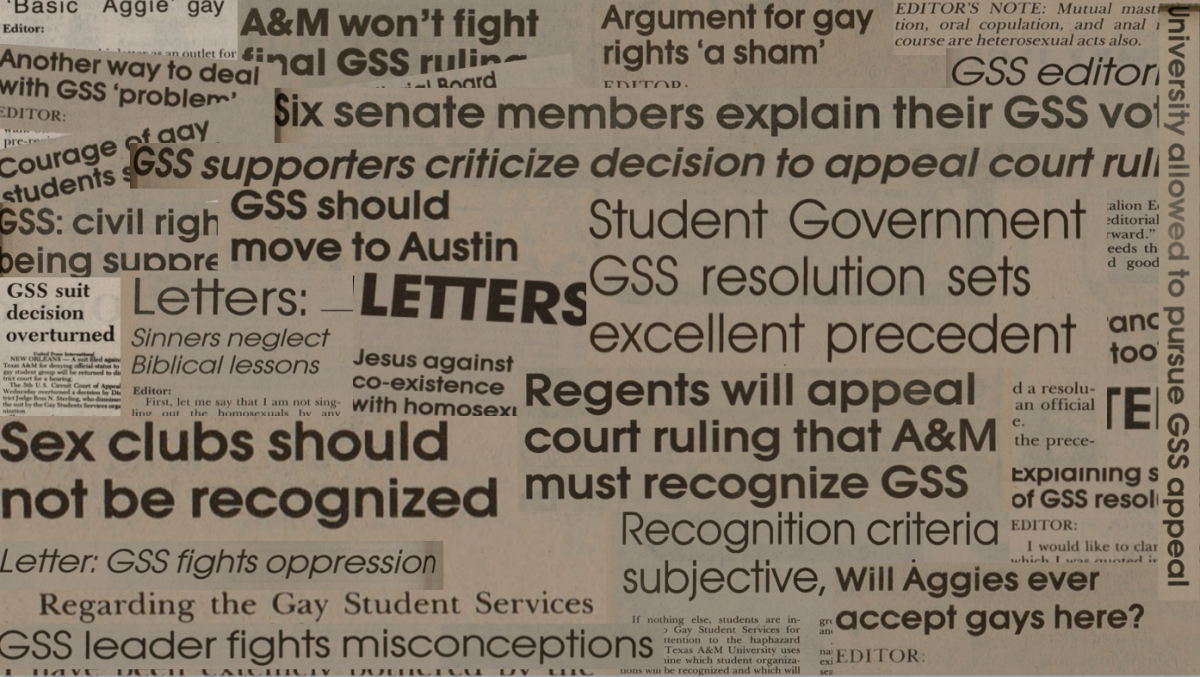

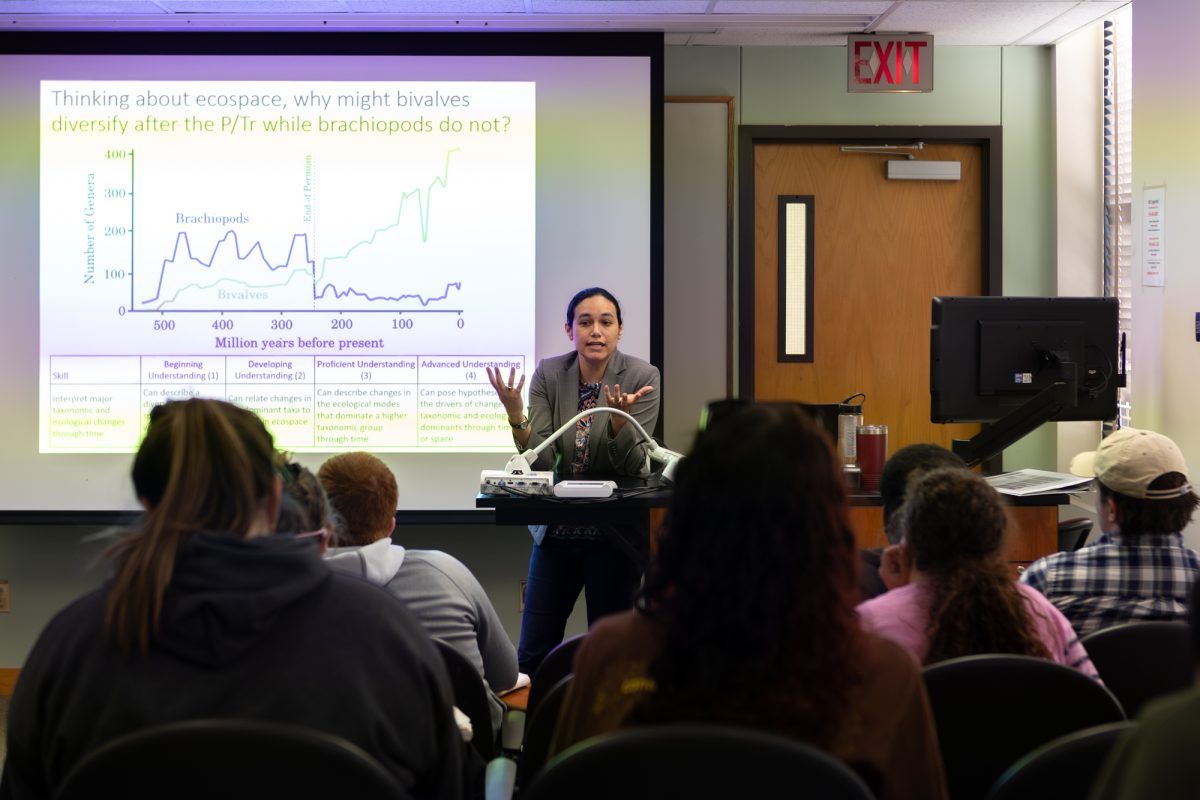

There were a number of interest, but one stood out. It had a student organization comprised of mostly gay students seeking recognition at a public university; a conservative campus in a conservative state overseen by a conservative administration; and, most importantly, a protracted legal battle that ended with a definitive court ruling.

In short, it had everything they needed.

The case was Gay Students Services v. Texas A&M (1984).