I am an Indian who cannot speak Hindi. Actually, I should share the truth: I am a half-Indian who cannot speak Hindi.

Growing up, I never felt a need to embrace my Indian culture. I practiced kathak, ate my grandmother’s samosas and watched the occasional Bollywood film. I knew of Shah Rukh Khan and the story of the Bhagavad Gita, but that was it. My Indian culture felt like a facade I could conjure up around other Indians to pretend that we shared similar childhoods. We didn’t.

As I got older, I felt the tension rise within myself about my own cultural identity. Being of a mixed race, I felt like a lost sailor from a sunken ship, stuck on a raft in the middle of the ocean between two islands, stranded. Who will find me first? Where will I wash ashore? Which ethnicity will identify me? I waited patiently for some magnificent event to define me. I didn’t realize that, in doing so, I was appropriating my own Indian culture.

During my freshman year, I wanted to join the clique of Indians at my university, but my attempted membership further discredited my heritage. Despite all my training to pass as seemingly Indian, I could not hide the holes in my poorly stitched cultural identity. The students saw right through my act, and I was ostracized. I could speak with them about all the latest films and music, but my experiences felt illegitimate, like a viewer recounting a televised event. I knew my rejection wasn’t the product of collective anger or frustration. Worse, it was because we just weren’t the same.

I was not like them. I couldn’t even speak my own language.

I broke off from the group, feeling underqualified for my membership, and I began to search for a fool-proof way to validate my ‘Indian-ness.’ This existential pursuit led me to a classroom filled with other self-doubting Indians.

I enrolled in an introductory Hindi class, an in-person course equivalent to a Language For Dummies book. The class was filled with American-Born Confused Desis, South Asians born in the United States who grow to develop a lifelong internal conflict between their American and Indian cultures. Later in life, I discovered that there are so many of us, someone felt the need to create an acronym: ABCD.

Sitting in my chair and leaning on the U-shaped linoleum table, I began to feel accepted. There are others equally as lost. I am not alone. We sat and chatted about our other classes until we heard a loud echo: “Namaste class.”

We turned to the back of the class and our professor was leaning against the doorway. He was wearing a loose white button down and worn-in jeans, with a faded leather satchel wrapped around his shoulders.

Also, he was white.

He grinned at his new apprentices, and I felt like a dandelion losing its body to the wind. I was shocked. I never imagined a non-Indian teaching me Hindi. I thought I would be learning my native language from a native. How can he possibly teach a class of Indian Americans their own tongue? Isn’t that insensitive?

He passed around syllabi, pulled out a chair, dragged it into the center of the classroom and sat on it, dropping his bag to the floor. Then, class began and we started practicing the alphabet. He drummed his retroflex “tha’s” and aspirated his “kha” sounds like a true Indian, while I developed a temporary stutter. I struggled to pass the air through my nostrils for the nasal “na’s,” and I could barely push the air out of my mouth for any aspirated noises. I spent my entire life listening to others speak around me, and even though I never understood the alien phrases passing through my ears, I thought I could at least copy the accent.

“Repeat after me,” he said. I couldn’t.

Then, we moved on to the script, Devanagari. He wrote the characters on the whiteboard. With each new drawing, I forgot the previous. I was lost, and I was frustrated. However, above all else, I was humbled.

People love exploiting Indian culture. Growing up in Los Angeles, I saw many middle-aged suburban women with aum symbols tattooed on their wrists and prayer beads wrapped around their rearview mirrors of their cars. I constantly met people who, upon discovering my mom’s ethnicity, proceeded to overshare their love of butter chicken and their “life-changing” experiences visiting the Taj Mahal. I could never escape Starbucks before hearing someone order a “chai tea,” and I avoided anyone wearing any “namastay in bed” merchandise like the plague. I judged their benign racism and I acted offended by their insensitivity.

However, how was I any different? I, just like the people I despised for appropriating Indian culture, cherry-picked my ethnicity. I never spoke to my mom in Hindi at home. I never learned how to cook any of my favorite dishes. I never asked to learn more — to connect more. Here I was, facing a non-Indian who was more Indian than I ever was. He embraced the culture with complete respect, honesty and curiosity. He was appreciative, and he never offended. He learned so much about India and Hindi, he could teach a college-level course on the language. The only advantage I had was my ancestry.

I realized that I was jealous of him, for he valued my culture more than I ever did.

Being a part of a culture is an active process. The moment one’s approach to a culture becomes passive, the relationship sours into appropriation. My professor was constantly challenging himself to learn about India, and he respected his limitations as an individual who could never truly be Indian. Meanwhile, I only absorbed external experiences I collided with as a child, which I later regurgitated to seem Indian.

I never felt Indian because I never actively connected with my culture. Since then, I have begun to explore my heritage, and I have grown to develop an identity that I continuously cultivate. I have developed a relationship with my Indian culture, and I am finally finding my way to my own ethnic background.

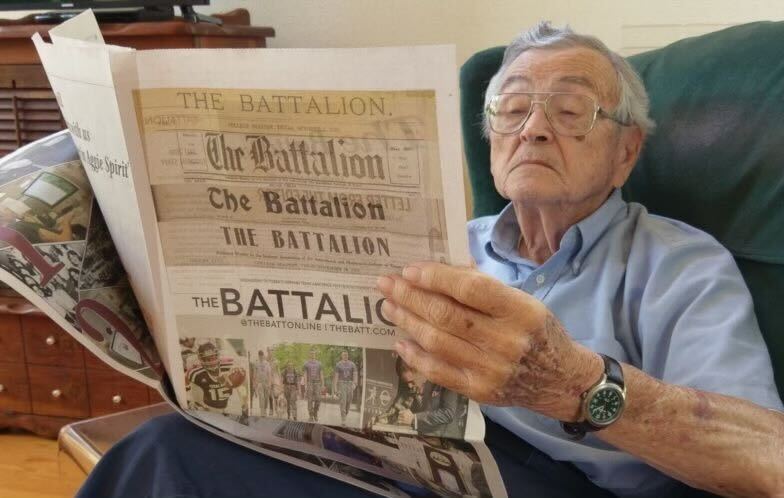

Maya Pimentel is an EnMed medical student and opinion writer for The Battalion.

Opinion: Am I Indian enough?

July 10, 2022

Photo by Photo courtesy of Maya Pimentel

Mehndi tattoos on the hands of opinion writer Maya Pimentel in New Delhi, India. Nov. 2017.

Donate to The Battalion

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas A&M University - College Station. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.