“I am a product of affirmative action. I am the perfect affirmative action baby. I am Puerto Rican, born and raised in the South Bronx. My test scores were not comparable to my colleagues at Princeton and Yale. Not so far off so that I wasn’t able to succeed at those institutions,” Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor said in a judges’ panel in the early 1990s.

As early as next October, Sotomayor may begin ruling on whether this country will continue the policies that she credits for her Ivy League education. Sotomayor is the perfect example of how the recipients of affirmative action — policy favoring groups that have faced historic discrimination or underrepresentation — are no less capable or full of potential than their peers, contrary to some arguments. In many ways, affirmative action is an investment into communities in America that have been long overlooked, but with these opportunities come an array of complexity. In some instances, affirmative action may statistically hurt Asian students’ chances of being admitted compared to other races, according to the New York Times.

It is difficult to balance needs and wants between every individual and the average public over decades. But on the whole, affirmative action has been life-changing and history-defining in instances like Sotomayor’s and those of millions of Americans. A decision that overturns the use of affirmative action may be disastrous for the lives of countless future students, though there may be some refuge through other avenues.

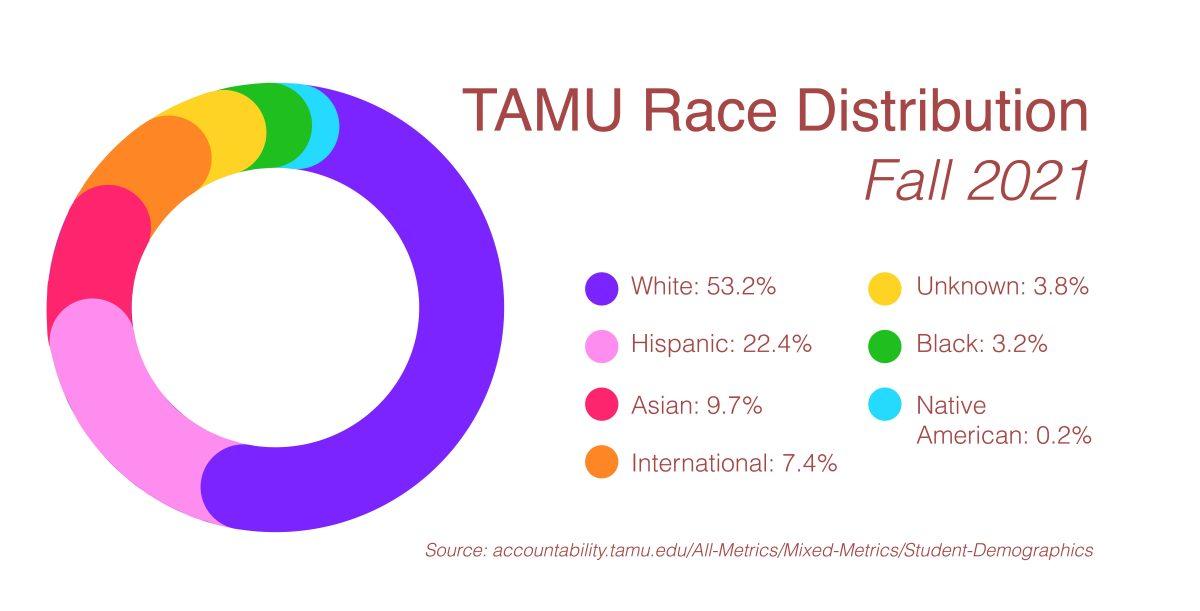

Despite not directly taking race into account during admissions, Texas A&M has seen its proportion of Black and Hispanic students increase to roughly the same levels as schools like the University of Texas, which do take race into account, based on analysis from the Texas Tribune.

After affirmative action was briefly ruled unconstitutional by the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, Texas instituted the top 10% rule. This decree guaranteed automatic admission to Texas public universities for students who scored in the top 10% of their graduating class. This allowed for students to enter A&M based on the relative success of their backgrounds and not in competition with students from all of Texas. This creates de facto affirmative action, as students from underfunded, underperforming and underrepresented schools have a chance to attend schools like A&M or UT without being passed over for students from more competitive high schools. Schools with historically large Black or Latino student bodies tend to fall into these three categories. In 2004, A&M also began the Regents Scholarship, which awards low-income first-generation college students with $20,000 over eight semesters. These policies are a great boon to students from all walks of life and backgrounds, giving Aggies opportunities that wouldn’t be possible otherwise, even evidenced by the experiences of yours truly.

The top 10% rule isn’t as successful as some hoped though. Many low-income or first-generation students seemed deterred from attending prestigious or flagship universities, like A&M. In this regard, recruiting at high schools and establishing scholarships like the Century Scholars to target specific schools managed to boost enrollment by double digits, according to economists at A&M, from some of these underrepresented areas. Solutions to these problems need to be multifaceted.

The effectiveness of direct affirmative action should not be discounted, though. Ivy League universities, like Harvard, have predicted that if they eliminated their considerations on race in admissions, Black and Hispanic admittance would almost be cut in half, according to Harvard’s Committee to Study Race-Neutral Alternatives. What strategies and policies work to deliver the best outcomes are as diverse.

In all levels of government, we need to be working toward solutions that create opportunities for those who most need them. Whether directly or indirectly, we need to continue rectifying the gaps in race and higher education. If the Supreme Court rules out the direct approach, then the top 10% rule combined with greater university outreach should serve as a model to continue guaranteeing more equitable access to higher education.

Zachary Freeman is an anthropology senior and opinion columnist for The Battalion.