Artistry follows no certain rules, ebbing and flowing as it progresses in creation. The only rules set are by the artist, yet even such rules can bear no limit. With enough ambition, the artist will soon follow a path not particularly set to the standards of historical art.

It is a break from these norms we are accustomed to (i.e. oil paintings, impressionism, “fine art”) that gives the artist the interpretation of being crazy. Craziness in terms of art can be seen in different ways. Either the creation of a piece is approached in a manner yet to be done, the final rendition of an artist’s piece is considerably disturbing, the artist themselves is concerningly unstable or all three. Or worse, ludicrously egotistical.

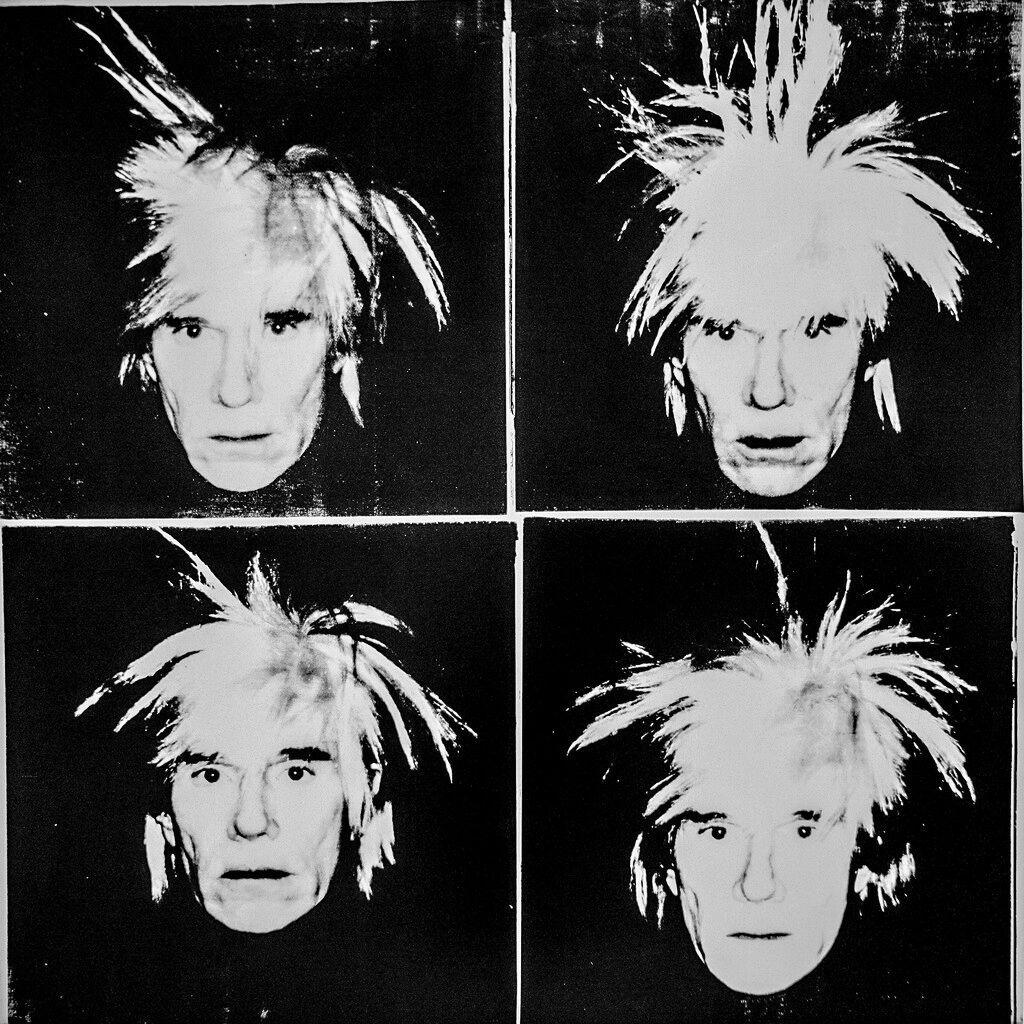

Andy Warhol’s use and popularization of pop art marked him as a target, branded as crazy. Inspired by the works of Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, Warhol focused his creation process on the alteration and reproduction of images, specifically those symbolic to consumer culture. It was deemed at first as plain plagiarism, but is now revered as a monumental stepping stone in art and culture. He was crazy enough to recontextualize images we have been so numbed to into provoking sets of figures and symbols that challenge our perspective of society and ourselves.

Francis Bacon is most memorable for his brilliant execution of the disturbing, especially in his triptych works, but most profoundly in his series of screaming Popes. Similar to Warhol — though Bacon came much earlier than Warhol — Bacon would reinvent paintings by other artists in his own style, such as that of Francisco Velasquez and Vincent Van Gogh, as a way to study and appreciate the medium of paint in his own image. Having a troubled life, Bacon saw the world as a blur, and with it gave the means to seek out the distinct and the abstract. He saw how paint gave way for the formation of shapes, but not the actual “true” object. With this, his grotesque imagery can show the beholder a distinct form, an abstract shape or an uncanny depiction that lies between.

Vincent Van Gogh, contemporarily a well-known and respected artist, was a victim to depression and suicide due to the shortcomings of his artistic career. Van Gogh presented the side of insanity that most overlook, especially when it comes to artists and creators, or anyone. To call what he experienced complete lunacy would be of great disrespect to him and anyone who suffers from depression, but to say he was stable would be no truth either. What gives Van Gogh’s work such sentiment is what he depicted throughout his lifetime: scenarios of hope such as “The Potato Eaters” and post-impressionist still-lives, like “Vase with Fifteen Sunflowers.” The lunacy doesn’t come from what he had or what he felt, but how he managed to keep it all inside.

Whether to sympathize or give the artists’ work the benefit of the doubt is ultimately up to the beholder. What we should be thankful for is the relationship between their madness and the status quo. Those who find a hidden comfort and shared connection with the hysteric, it solidifies the human connection and gives hope for those who feel they are alone with their thoughts. For those who disdain these works of art, the madness elevates other more “refined” pieces of work, making the classics the “cream of the crop” rather than just another painting that managed to set the standard.

It’s these pieces of lunacy that make us see that our world isn’t just limited to our own senses, that others will have different expressions that confuse or scare us. Those who turn a blind eye on such pieces and find comfort within the boundaries of their well-adjusted comfort are those who squirm in the face of challenge, difference and ultimately truth. While those who at least find the means to acknowledge such discomfort may find they are no better than the estranged artist, or rather, no different.