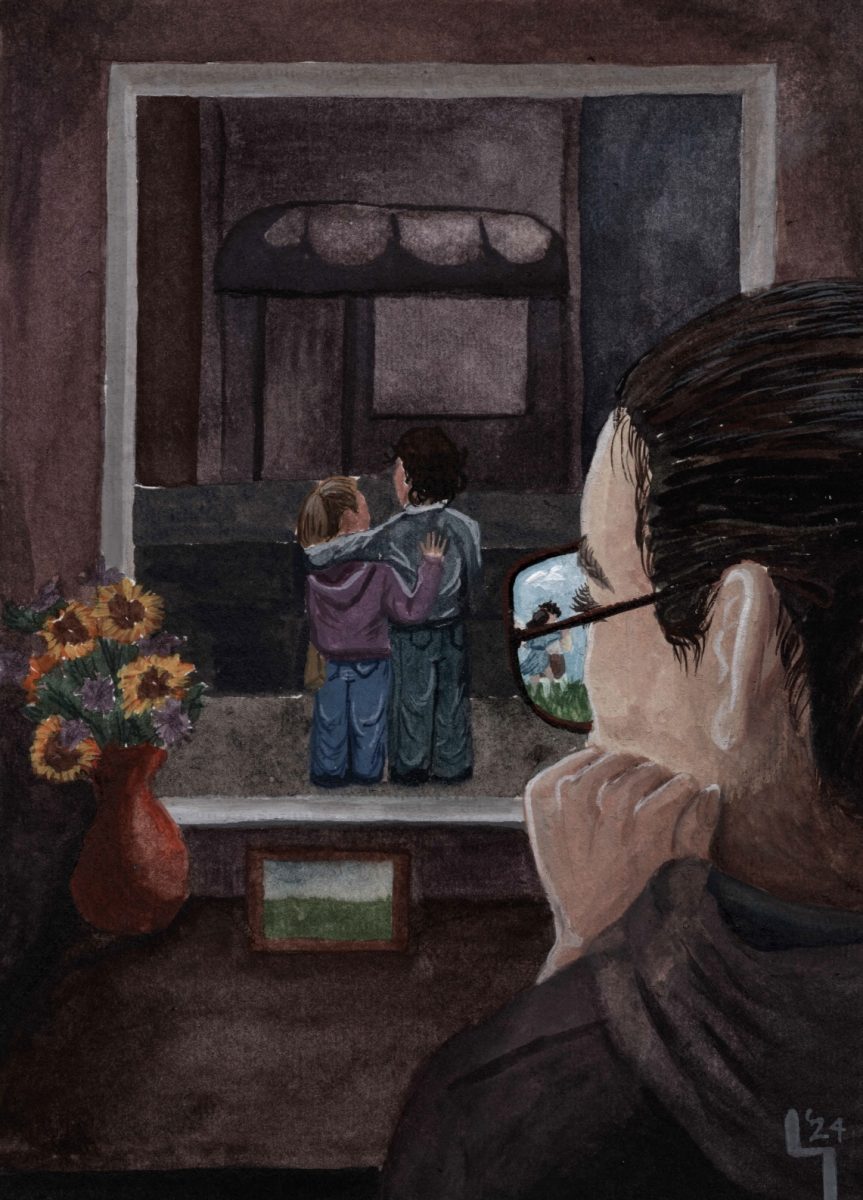

The officer spoke with Sina for about an hour.

“How did you two meet?”

He was referring to Sina’s wife, Niloofar. The two had met, if you must know, as childhood neighbors in a city to Iran’s north, near the Caspian Sea. They started dating in 2013 and married four years later. They received their green cards in 2018 and are currently Ph.D. students at Texas A&M.

At the moment, however, it was early January, and the couple was enduring a secondary inspection at George Bush Intercontinental Airport. Upon attempting reentry to the United States, the official who had checked their passports suddenly called over two escorts and instructed the pair to follow them.

Exhausted from 20 hours of travel, the couple was escorted into a separate room where they watched as those of other nationalities came in, were presumably asked several questions, and allowed to leave. “It was all very smooth,” Niloofar explained during our interview. They waited for over an hour before she eventually fell asleep. Finally, an officer called Sina in.

“How was your trip?”

It had gone well, if you must know. They had spent the first leg visiting family and the second in Dubai. At some point, American forces had killed a high-ranking Iranian official, but Sina was too busy enjoying himself on the beach to let it ruin his vacation. One can imagine the opening lines of his travelogue: “Soleimani died today. Or yesterday, maybe. I don’t know.”

“What are your political views?”

They don’t have strong political views, if you must know. That makes them something of a rarity in Iran, a country where, Niloofar said, “people have to be very much involved in politics because it really affects their lives and the situation is very unstable.” Their sensibilities are more common for immigrants, however: If they had strong ties to their home country, they would have never immigrated in the first place. Here they worry airport officials will pull them over for secondary inspections.

“What are your religious views?”

At this point, suspecting the questions were inappropriate, Sina pushed back. Still, the officer was unmoved.

“No, you’re not a U.S. citizen,” the officer said. “You’re an Iranian citizen. You don’t have the right to just ignore my questions or try not to answer them.”

That, you should know, is inaccurate, the purest distillation of bureaucratic doublespeak. To illuminate the legalities of immigration, I spoke with Huyen Pham, a professor at Texas A&M’s School of Law.

Pham said even though green card holders are not American citizens, they retain constitutional rights such as the Fifth Amendment’s guarantee of due process. National security can sometimes be a trump card, but generally speaking, green card holders do not have to answer questions about race, religion or political affiliation. But not answering them might still lead to removal proceedings.

“It’s not like you [can] refuse to answer questions, then you get admitted and it’s over,” Pham explained, but “a judge couldn’t remove you because you’re a Muslim.”

Most immigrants don’t know these technicalities, and if they do, the spectre of removal is enough to make compliance seem reasonable. (Incidentally, this is how the erosion of civil rights works, by making their surrender seem “reasonable.”) So, being a reasonable man, Sina answered the officer’s questions. “Who did you meet? What does each of your family members do? Are you sure you don’t have strong political views?” It all lasted for about an hour. Then the officer asked Sina to leave, and they brought in Niloofar to corroborate his responses.

Only afterwards — following some two and a half hours of waiting and interviews — was the couple informed they had been pulled aside for not completing a Customs Declaration Form. It is a simple entry document which asks such invasive questions as: “Are you bringing any fruits and vegetables into the country? How about meat or animals? Have you been on a farm or ranch recently?”

It does not mention religion, political affiliation or family ties.

Even though they had traveled to and from Iran multiple times, neither Sina nor Niloofar had experienced this situation before. While deplaning, they had asked several airport officials if they needed to fill out a Customs Declaration Form, and each time the officials had told them no.

Neither Sina nor Niloofar could make sense of that.

Following their release, they retrieved their baggage, got in their car, and drove the hour and a half down Highway 6 toward College Station. Sina is more placid than Niloofar and has thought about the inspection less than she. Niloofar, however, remains haunted by a creeping ambivalence, an ambivalence which makes her wonder — for the first time since she came to America — whether she immigrated to the wrong country.

She still doesn’t know.

Implications of secondary inspection

February 26, 2020

Photo by Creative Commons

George Bush Intercontinental Airport is one of the largest airports in the United States and is located in Houston.

0

Donate to The Battalion

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas A&M University - College Station. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

More to Discover