Editor’s note: The Battalion does not publish the names or identifying information of rape and sexual assault victims. The names of victims and assailants in this article have been altered or removed to protect the subjects’ identities.

Content warning: This article discusses sexual violence and predatory behavior.

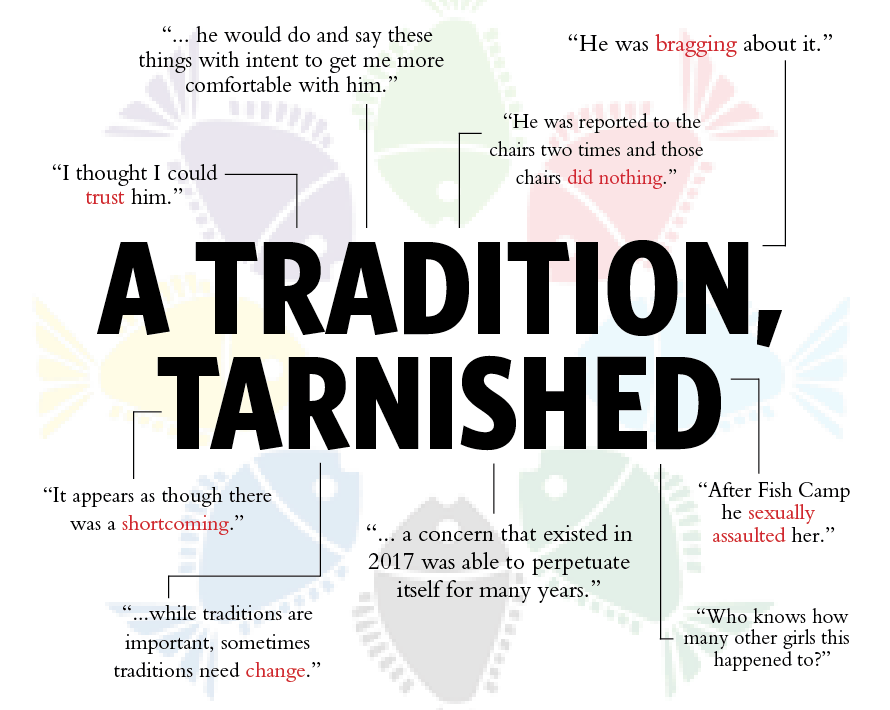

“I thought he was someone I could trust.”

Journalism junior, “Ashley,” said this of the male counselor in her 2018 Fish Camp Discussion Group, who was supposed to “offer advice about classes, College Station and anything else you need as you begin your journey as an Aggie,” according to Fish Camp’s website.

Ashley’s D.G. dad sexually assaulted her four months into her freshman year at Texas A&M — the unwanted campus welcome that she said stole her joy about the school.

Boldly stated on the front page of its website, Fish Camp, founded in 1954, is “A freshman’s first tradition” at A&M. However, sexual assault and harassment have woven their way in as a hidden part of the tradition as current students — D.G. “moms” and “dads” — are placed in positions of power over incoming freshmen. The result is an established culture of hookups, grooming and sexual assault and harassment among counselors that extends well beyond the four-day summer retreat held two hours away from College Station. In addition, a failure to adhere to proper protocols — in which claims of abuse and harassment against counselors are passed along to director staff and faculty advisors — has created a climate that protects abusers from repercussions and subjects freshmen to predatory behavior.

Lauren Carroll Spitznagle, executive director of the Brazos Valley Sexual Assault Resource Center, said it is “common knowledge” that students have been assaulted through Fish Camp.

Power dynamics, grooming, hookups

The unequal power dynamic that Fish Camp creates between counselors and incoming freshmen makes it easy for someone who has not learned healthy boundaries to assert predatory behaviors, Carroll Spitznagle said.

“Whenever you have someone that’s in a position of power like that — especially with students that come from all over the world with different cultures and backgrounds — it becomes, unfortunately, a way for survivors to be preyed upon,” Carroll Spitznagle said.

Ashley said when she met her D.G. dad on the first day of Fish Camp, she thought he was nice and trustworthy. Once classes began, Ashley said her D.G. dad remained in contact with her and often told her to call him if she ever needed a ride from Northgate, which he insisted was commonplace between D.G. parents and their freshmen.

On the night of Dec. 1, 2018, Ashley called her D.G. dad for a ride home from Northgate, but when he picked her up, he locked Ashley inside his car and tried to force her to kiss him and perform oral sex. Afterward, he drove them to his apartment in Park West instead of to her house, as she had asked, and attempted to rape her.

In hindsight, Ashley said she realized there had been red flags, like how he would ask the freshman girls if they had boyfriends and when he saved his contact name in Ashley’s phone with a smiley face. Ashley said she now sees these subtle actions as her D.G. dad grooming her because he was ultimately able to build trust and put her in situations that would have otherwise been weird.

“I was a freshman. I was young, you know? I was coming into this camp as brand new; I hadn’t been fully educated on the concepts of grooming and sexual assault, so I never thought it was weird,” Ashley said. “Looking back now, he would do these things and say these things with intent to get me more comfortable with him.”

After confiding in other members of her D.G. following the assault, Ashley said she was told her counselor had also assaulted his Fish Camp partner and another freshman in their D.G.

“His D.G. partner was very uncomfortable with him from the start. [She] asked to get a new partner, and they told her no,” Ashley said. “The organization told her no, and she had to stay with him.

“After Fish Camp, he sexually assaulted her.”

Additionally, Ashley said she was told by her D.G. mom that her assaulter was also reported to chairs for sexually assaulting freshmen in 2017 and 2019. Because of those chairs’ failure to report up to the director staff, as is protocol, he was able to re-apply to be a counselor again and again. Ashley said he ultimately graduated from A&M in May 2020 with no consequences.

“He was reported to chairs two times, and those chairs did nothing,” Ashley said. “And because those chairs did nothing [in 2017], I was sexually assaulted.”

Ashley’s D.G. dad denied the allegations against him in a comment to The Battalion and declined to comment further.

Even though Ashley reported her assault to Title IX two years later, Fish Camp’s current Head Director Eric Muñoz, Class of 2021, said it is not common for victims of Fish Camp-related sexual assaults to report their offenders. However, he said if someone told him assault is common within the organization, he would be “very saddened, but I also would not be as surprised as others.”

In addition to sexual assault, Fish Camp is also a common place for counselors to meet dating or hookup partners, either among other counselors or, sometimes, even the freshmen, as was the case with now-junior “Grace.”

Grace said she began hooking up with her D.G. dad within the first month of classes her freshman year, which Muñoz said is against Fish Camp policy — counselors cannot be romantically involved with any freshmen until their continuity program and membership ends in October each year. However, this policy is not listed in Fish Camp’s Constitution or by-laws.

Grace said she quickly figured out her D.G. dad had ulterior motives for being a Fish Camp counselor from the start.

“He told me he did it to [hook up with freshmen] … and also to make friends,” Grace said. “He was bragging about it.”

Muñoz said Fish Camp has a strict no-dating policy, and counselors are encouraged to “keep it PG” with the freshmen and other counselors during camp until continuity ends.

“Counselors are told time and time again that their role is to serve freshmen, it’s to be a resource and to be a mentor,” Muñoz said.

Despite these policies and constant reminders about Fish Camp’s main missions, Grace said she has discovered it’s really common for students to pursue leadership roles within the organization for the wrong reasons and to overlook its dating policies.

Reporting sexual assault on A&M’s campus

Denise Crisafi, Ph.D., a Health Promotion coordinator within the Offices of the Dean of Student Life, said A&M defines sexual harassment in University Rule 24.4.2 in accordance with federal law as “any type of unwelcome sexual advance” made by students, faculty, staff or campus visitors. This includes sexual favors as well as verbal and non-verbal communicative conduct of a sexual nature that is “severe, persistent or pervasive enough to [prevent access to] an educational, living learning environment,” Crisafi said.

Separately, sexual assault is definitively three different acts, Crisafi said: rape, fondling and incest. She said there is no scale for these acts in terms of importance, so no one’s trauma is invalid.

“I think it’s really important for our campus community to understand that a lot of times, our initial reaction is to think of [sexual assault] as rape,” Crisafi said. “And that’s true, and it’s incredibly valid. But it also includes other things that can happen in connection with it … or without the definition or action of rape being present.”

Crisafi said national statistics show the risk of sexual assault goes up within the first six to eight weeks of the fall semester, particularly among freshmen.

“Usually the risk of experiencing sexual violence and or alcohol poisoning and intoxication goes up because you have 17- [and] 18-year-old young people with a newfound independence,” Crisafi said.

University Rule 24.1.6 defines consent as “clear, voluntary and positive verbal or non-verbal communication that all participants have agreed to the activity.” Crisafi said someone must be of conscious and sound mind in order to make a decision to engage in sexual intercourse. Therefore, individuals cannot give consent if they are intoxicated, sleeping or passed out, or if they have an intellectual, emotional or physical disability that prevents them from volunteering agreement.

Assistant Vice President of Compliance and Title IX officer Jennifer Smith said if a campus member is found to have violated these school rules after an investigation is completed through the Title IX office, then they will be disciplined by the university, which could include probation, suspension or expulsion. The report is not sent to the police unless the accuser chooses to open a criminal investigation.

“We try to give as much control as possible to the victim,” Smith said. “If the victim doesn’t want to report to the police, then they don’t have to. It’s totally up to the victim.”

However, Smith said proceeding with a formal investigation with Title IX requires obtaining accounts from both parties as well as witnesses, writing up a report and holding a hearing with a neutral hearing officer before a final decision is made. Due to federal Title IX regulations, A&M’s Title IX office cannot offer anonymity to a campus member who chooses to report an offense, as the office is legally obligated to disclose the victim’s name to the offender if they are accused, Smith said.

A failure to serve freshmen

Muñoz said Fish Camp chairs are obligated to report incidents of sexual assault to the organization’s advisors and support staff. If a counselor is reported to have assaulted a freshman or other staff member, he said the camp chairs would meet with the counselor and accuser in a small group first, and then possibly report up to the organization’s advisors.

“Chairs are in the first line of response,” Muñoz said. “They’re the front line, and they are responsible to relay that information back to director staff and the advisors.”

However, as in Ashley’s case, the chairs do not always follow this protocol. The chairs — students themselves — are relied upon to enforce the rules, echoing a similar situation in A&M’s past that, too, brought disaster after a lack of oversight by anyone above the student leader role: The 1999 Bonfire Collapse.

During the U.S. Fire Administration’s investigation of Bonfire’s collapse, it was discovered that “the physical failure and causal factors were driven by an organizational failure” on both the students’ and university officials’ parts. And “since [Bonfire was] a student function, university officials rely upon the students to enforce the rules.” This description accurately depicts Fish Camp’s current status where camp chairs do not pass sexual assault allegations up to executive or faculty advisor levels, allowing predatory D.G. parents to continue in leadership roles until they graduate.

Muñoz himself is an undergraduate student, and the only non-student leaders involved in Fish Camp are two advisors from the Division of Student Affairs, Bradley Burroughs and Andrew Carruth. Burroughs and Carruth declined multiple requests for comment from The Battalion.

Fish Camp’s response

The lack of anonymity from A&M’s Title IX office is why Ashley did not go through with a formal investigation against her D.G. dad, she said. Instead, according to emails obtained by The Battalion, Ashley reached out to the Fish Camp director staff on Oct. 1, 2020 to share her story and ask how they would work to prevent future assaults from happening within their organization.

“Where I feel Fish Camp failed myself and the other girls sexually harassed/assaulted is from the lack of action taken by your leadership staff,” Ashley’s email reads. “Had he been removed as a counselor after he was first reported to camp chairs in 2017, my D.G. mom and I never would have been sexually assaulted and my D.G. sister never would have been cyber sexually harassed. In addition, because he was a three-year counselor, who knows how many other girls this happened to?”

Former Head Director Ryan Brown, Class of 2020, responded to Ashley’s email with an apology and a recognition of the organization’s failure.

“It appears as though there was a shortcoming, these protocols were not followed by chairpersons, and Director Staff was never notified,” Brown said in the email. “Thus, a concern that existed in 2017 was able to perpetuate itself for multiple years. Had this individual’s behavior been reported as individuals in Fish Camp are trained, it would have been reported to the Title IX office and Offices of the Dean of Student Life by Fish Camp to determine if that individual would be able to continue in their role with Fish Camp that year and future years.”

While Muñoz confirmed cases have been swept under the rug in the past, as current head director, he said he intends to ensure that all Fish Camp chairs and counselors are well-equipped to prevent and report incidents of sexual assault and harrassment moving forward. To achieve this, Muñoz said he is trying to certify all chairs through A&M’s Green Dot Bystander Intervention program for the upcoming 2021 camp sessions. This training is not yet mandatory, though it has been in previous years, Muñoz said.

Crisafi said Health Promotion currently provides the same sexual assault training for Fish Camp counselors and freshmen, which focuses on teaching the four steps of trauma-informed care: Practice active listening, respect a survivor’s independence, help them get to safety and share resources available on campus. Health Promotion gives this information to freshmen at Fish Camp during a 25-minute presentation in each camp room, Crisafi said, while counselors receive an hour and a half extended version of this training on bystander intervention before camp.

“Those [counselor training] rooms are very large, obviously, so sometimes it can be a lot to manage,” Crisafi said. “We try to equip them with the tools to be able to respond to [sexual violence] in a way that’s going to be trauma-informed and meaningful. So, feeling comfortable and empowered to call out that behavior and say, ‘This doesn’t fit the mission of our organization, this isn’t what we’re about.’”

However, Crisafi said another training resource Health Promotion offers that could be beneficial to Fish Camp counselors is the STAND Up Workshops. These are typically in-person, hands-on workshops providing “information about sexual assault, dating violence, domestic violence and stalking; social perspectives; the impacts of trauma on the brain; listening techniques; tools for mandated reporters; and campus and community resources,” according to its website. Due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, Crisafi said the office has been offering the workshops through live Zoom sessions.

These workshops are not currently required for any Fish Camp staff, though Crisafi said she believes they could be in the future.

Carroll Spitznagle said she wishes the university would allow the Sexual Assault Resource Center, or SARC, to do on-campus trainings for Fish Camp staff and other leaders on campus.

“I would love for [Fish Camp’s director staff] to allow us to come in and do training,” Carroll Spitznagle said. “We offer training on consent, healthy relationships [and] human trafficking, both in Spanish and English.”

According to SARC’s website, the center also “provides information on the definition of sexual harassment, the applicable laws in Texas and an overview of prevention methods.”

Ashley said despite her unwanted and disappointing welcome to A&M, she still believes Fish Camp is an important organization that can do good. However, she hopes for big changes within the organization to stop it from perpetuating a culture where hookups and harassment or assault are normalized.

“I personally love A&M’s traditions, and I think they are slowly starting to change over time… But I think it does show that while traditions are important, sometimes traditions need change,” Ashley said. “That was my welcome to A&M. That happened to me, and it stole my joy about A&M.”

Update, 9:21 p.m. 2/04: After a follow up interview with Spitznagle, it is clear that she did not intend to imply that sexual assault is common knowledge among her peers, but rather among students at Texas A&M. The article has been corrected to reflect this.

Editor’s note: A previous version of this story stated that Lauren Carroll Spitznagle, executive director of the Brazos Valley Sexual Assault Resource Center, said “it is ‘common knowledge’ among her peers that students have been assaulted by Fish Camp staff.” This has been corrected to say “it is ‘common knowledge’ among her peers that students have been assaulted through Fish Camp.”

The Battalion regrets this error, but stands by the reporting in this story.

Below is an excerpt from transcript of Myranda Campanella’s interview with Spitznagle:

Below is a statement from Spitznagle:

“Too many people are victims of sexual violence in the United States. Sadly that includes people in our community and students at Texas A&M University.

While I admire the ambitious effort by the Battalion to focus attention on the issue of sexual violence, I take exception to a statement attributed to me prominently in the article.

I never said or meant to say or meant to suggest that it is “common knowledge” among advocates against sexual assault in this community that Fish Camp is a hotbed of sexual violence.

What I know that we sometimes have heard talk among students about sexually-charged behavior at Fish Camp and about incidents of sexual violence that occur among people who have met at Fish Camp. This kind of second and third hand talk is not uncommon.

We jealously guard the privacy of all sexual assault victims who come to us for help.”